Chief Master Marsh:

1. The claimants applied by application notice dated 22 August 2018 for an order permitting the second claimant to use certain documents disclosed by the 1 st to 4 th defendants (“the Sandoz Defendants”) in this claim in a claim in Belgium between the second claimant and Sandoz NV (“Sandoz Belgium”). The two claims are part of global litigation between members of the GlaxoSmithKline and Sandoz groups of companies. In Europe there are claims in several jurisdictions including England and Wales, The Republic of Ireland, Germany, The Netherlands and Belgium.

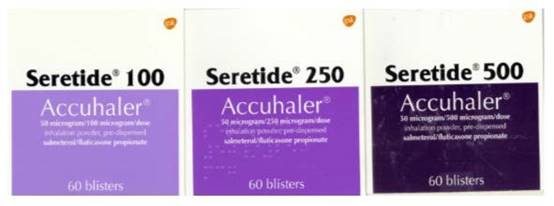

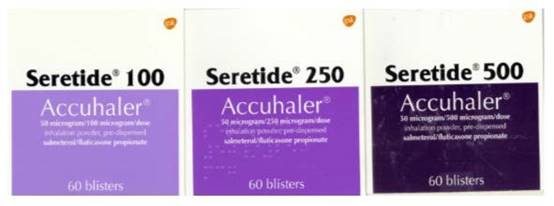

2. Seretide (known as Viani in Germany and Advair in the USA), which is now out of patent, is used by patients for the treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). It is a combination of two preventers, a Long-Acting Beta-Agonist and an Inhaled Corticosteroid. The claimants say it was an innovative product at its launch. It is sold in two types of inhaler; a ‘boot shaped’ metered dose inhaler (MDI) and a dry powder disk inhaler (DPI). The MDI is marketed in the UK under the name ‘Evohaler’ and the DPI under the name Accuhaler. Both are available in different dosages.

3. The second claimant was the registered proprietor of a colour Community Trade Mark number 3890126 for the combination of purple 2587C and purple 2576C registered with effect from 16 June 2004. However, the Community Trade Mark was declared invalid on 11 November 2016 on the counterclaim by the Sandoz Defendants in these proceedings by HH Judge Hacon (sitting as a judge of the High Court) and his decision was upheld by the Court of Appeal on 6 April 2017.

4. These proceedings now comprise solely a claim by the claimants in passing off. The core claim is set out in paragraphs 13 and 14 of the re-re-amended particulars of claim:

“13. The Claimants’ Seretide Accuhaler and Evohaler products are sold in a get-up and packaging which are distinctive of the Claimants. The Claimants or one or more of them are the owners of a significant goodwill in the business of selling Seretide Accuhaler and Evohaler products in the UK which has become associated in the minds of the trade and public with the particular get-ups and packaging in which the said products are sold.

14. In this action the Claimants will rely on the following distinctive indicia either alone or in combination (hereinafter ‘the indicia’ ):

14.1 as regards the get-up of the Seretide Accuhaler inhaler itself (as shown in the examples below):

14.1.1 the use of the purple colours (each either alone or in combination as independent distinctive indicia);

14.1.2 the respective positions of the purple colours around the product and the central position of a white label; and

14.1.3 the overall shape and size of the Seretide Accuhaler product itself in the open and/or closed position;

14.2 the use of the colour purple and white on Seretide Accuhaler packaging as shown in the examples below;

14.3 the prominent use of the numbers ‘100’, ‘250’ and ‘500’ on the central white label of the Accuhaler and the outside of the packaging;

14.4 the use of the purple colours … on the Evohaler inhaler as shown in the examples below; and

14.5 the purple and white on the Seretide Evohaler packaging as shown in the examples below.

5. The Sandoz Defendants launched a generic product named “AirFluSal Forspiro” in the United Kingdom in 2015 and elsewhere internationally variously from 2014 onwards. The products are both prescription-only and they are marketed and sold as boxed inhalers.

6. Pictures of the AirFluSal product as it was launched in Ireland are below:

7. The packaging of the two competing products can be seen from the following images:

8. The claimants allege that the Sandoz Defendants chose AirFluSal Forspiro’s get up with the deliberate aim of deceiving or creating confusion in the mind of the relevant public. The Sandoz Defendants accept that the question of whether the public are deceptively confused may take into account the Sandoz Defendants’ intentions and documents relating to the design history of the AirFluSal Forspiro dating back to 2003 have been disclosed by the Sandoz Defendants in this claim.

9. The trial of this claim was due to take place in October 2018. However, on 3 July 2018 Mr Rosen QC (sitting as a deputy judge of the High Court) made an order vacating the trial date and directing that the fifth, sixth and seventh defendants be joined as parties to the claim. The trial has now been re-fixed to take place in July 2019. The fifth defendant, Sandoz AG, is part of the Sandoz group of companies. The sixth and seventh defendants are independent companies (together “Vectura”) which were involved in the design of the AirFluSal Forspiro product.

10. The disclosure exercise between the claimants and the Sandoz Defendants has been very substantial. It involved the Sandoz Defendants reviewing 406,300 documents using 50 legally qualified reviewers. This led to the subsequent disclosure of slightly in excess of 75,000 documents to the claimants.

11. There is a marked contrast in the manner in which litigation is conducted in England and Wales on the one hand and Belgium (and most other Civil law countries) on the other hand. In England and Wales, the ability to obtain disclosure that is adverse to the other party’s claim is an important feature of litigation. However, the evidence provided in connection with the application shows that disclosure is only available in a very limited form in Belgium. One of the issues to be determined is whether disclosure obtained in this jurisdiction should be made available to a party that is engaged in litigation in a jurisdiction where disclosure, if not unknown, is very limited in scope.

12. The claimants’ application is to use the documents in the existing proceedings in Belgium and any new action the second claimant brings in Belgium against to second to seventh defendants. What the claimants have in mind is explained in more detail in the 10 th witness statement of Eifion Morris (“Morris 10”). The uses to which the second claimant wishes to put the documents are:

“(i) to seek advice from its Belgian counsel as to whether the documents merit being adduced as evidence in the Belgian action on the basis that they correct factual misstatements and disprove arguments made by Sandoz Belgium in those proceedings;

(ii) to seek advice from its Belgian counsel as to whether the documents merit bringing proceedings in Belgium against the second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and/or seventh defendants in Belgium; and

(iii) if the second Claimant’s Belgian counsel believes that they merit the action described above (in whole or part) then to use the documents for those purposes in the Belgian action and any new action against the second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh defendants in Belgium”

13. The application was dealt with on the basis that if an order is to be made, use of the documents is contingent upon the second claimant first obtaining advice from its lawyers in Belgium about the appropriateness of using them, or some of them, for the purposes Mr Morris explains. But it is not part of the second claimant’s application that it would need to refer back to this court before using the documents, if the advice obtained is to the effect that use of the documents is merited.

14. EU Directive 2008/95/EC (as recast in EU Directive 2015/2436) “The Trade Mark Directive” has been implemented in the Benelux Convention on Intellectual Property. On 2 July 2015, the second claimant became the registered owner of a Benelux trade mark registered under number 0977861 used in relation to Seretide. The registration is for a single colour described as “Violet 2587C” in classes 5 and 10 (“the Benelux mono-colour trade mark”).

15. The trade mark registration covers Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. The registration pre-dated the launch of the AirFluSal Forspiro product in Belgium and the launch has not yet taken place.

16. On 3 November 2015, Sandoz Belgium, which is the holder of marketing authorisation for the AirFluSal Forspiro product in Belgium, brought a claim before the Dutch-speaking Court of Commerce of Brussels (“the Belgian Court”) seeking, amongst other things, a declaration of invalidity in relation to the Benelux single colour registration (“the Belgian Claim”).

17. There has been some issue between the parties about the scope of the Belgian Claim. Mr Christian Dekoninck, who represents Sandoz Belgium in the Belgian claim, describes the issues in the following way:

“1.1 The Benelux mono-colour trademark cannot be considered distinctive ab initio. European and Belgian case law confirms with regards to single colours that distinctiveness without the prior use is inconceivable save in exceptional circumstances. No such circumstances were established by the second claimant.

1.2 Second, the Benelux mono-colour trademark is merely descriptive as it only serves to designate the purpose (combination product), composition or the strength of the medicinal product.

1.3 Third, the second claimant does not establish that the colour trademark may have acquired distinctiveness through use.

1.4 Finally, the registration of the Benelux mono-colour trade mark is contrary to the public interest as it unduly limits the possibility of other manufacturers to use the basic colour purple for descriptive purposes.”

18. According to the second claimant, Sandoz Belgium has argued in the Belgian Claim that:

(1) consumers do not associate the purple colour with Seretide or perceive it as a trademark of the claimants. Instead, the colour purple is part of an international colour code for inhalers informing consumers that the inhaler contains a combination of a long acting bronchodilator and inhaled corticosteroid;

(2) the second claimant only applied for the Benelux single colour trade mark to block the Sandoz Belgium product accessing the Benelux market in full knowledge that it does not have any rights in the single colour alone. This is said to constitute an act of anti-competitive behaviour.

19. The second claimant has defended the Belgian Claim and counterclaimed for infringement of the Benelux trademark. Although (surprisingly) it was not mentioned by Mr Dekoninck, it is now accepted that the second claimant’s counterclaim includes a claim under article 2.20(1)(c) of the Benelux Convention on Intellectual Property (reflecting the Trade Mark Directive Article 10(2)(c)) for taking unfair advantage. The unfair advantage claim has been a subsidiary part of the second claimant’s counterclaim in Belgium, but it has assumed significance in the application because the type of documents that may be relevant to it are wider than in relation to the other issues.

20. On 12 January 2017 the Belgian Court decided that the Benelux mono-colour trade mark was valid but was not infringed by the possible marketing of the AirFluSal Forspiro inhaler. Both parties have appealed that decision and both parties have already filed appeal briefs in accordance with a trial schedule agreed upon between them. It is now common ground that the appeal is a re-hearing of the claim. At one time it was said the second claimant’s application was urgent and the Sandoz Defendants questioned whether further evidence would be admitted by the Belgian Court. It is now accepted that the court in Brussels will abide the outcome of the application before me and it is open to both parties to file additional evidence with the second round of appeal briefs. The parties have agreed that, if the second claimant is successful on its application, to a greater or lesser degree, sequential additional briefs will be filed with the second claimant going first. This will be followed by an oral hearing of the appeal.

21. CPR 31.22 provides:

“(1) A party to whom a document has been disclosed may use the document only for the purpose of the proceedings in which it is disclosed, except where –

(a) the document has been read to or by the court, referred to, at a hearing which has been held in public;

(b) the court gives permission; or

(c) the party who disclosed the document and the person to whom the document belongs agree.”

22. The principles that apply to an application made to obtain the court’s permission to use documents for a purpose other than the proceedings in which the documents were disclosed has been considered in a number of authorities. Mr Hickman who appeared for the claimants provided a helpful summary of the authorities which I adopt.

(1) In Crest Homes v Marks [1987] AC 829 at page 859, in an era before the Civil Procedure Rules came into force, Lord Oliver referred to the need for “cogent reasons” to release the implied undertaking but went on to state at 860 B-C that the cases:

“illustrate no general principle beyond this, that the court will not release or modify the implied undertaking given on discovery save in special circumstances and where the release of modification were not occasion injustice to the person giving discovery.”

(2) The Court of Appeal has since emphasised that “cogent reasons” are required before a collateral use is allowed but that the overall issue is to be addressed as a balance between the competing interests of justice. Would permitting use cause injustice? If so, this has to be balanced against the interests of justice in allowing the use:

i. “it is important under the CPR to have in mind the overriding principles when considering whether to lift an order made under CPR 31.22. The most important consideration must be the interests of justice which involves considering the interests of the party seeking to use the documents and that of the party protection by the CPR 31.22 order. As Lord Oliver said, each case will depend on its own facts”: SmithKline Beecham plc v Generics (UK) Ltd [2004] 1 WLR 1479 at [37] (Aldous LJ).

ii. “Since ultimately the public interest in the due administration of justice is based on the interests of justice, and all the authorities considered in this judgment speak of the need to balance the two public interests in play, the absence of any special reason for fearing injustice is an important consideration”: Marlwood Commercial Inc v Kozeny [2005] 1 WLR 104 at [45] (Rix LJ).

iii. “The court will only grant special permission under rule 31.22(1)(b) if there are special circumstances which constitute a cogent reason for permitting collateral use … There is a strong public interest in facilitating the just resolution of civil litigation … It is for the first instance Judge to weigh up the conflicting public interests.” Tchenguiz v Director of the Serious Fraud Office [2014] EWCA Civ 1409 at [66(i), (iii) and (v)] (Jackson LJ).

23. Mr Hickman also drew attention to the decision in Cobra Gold Inc v Rata [1996] FSR 819 in which Laddie J set out a number of principles he considered the court should take into account. His observations were referred to as being ‘useful’ in SmithKline . The court should consider:

(1) The extent to which collateral use will cause injustice.

(2) Whether the proposed use is outside litigation (such as disclosure to the press or for commercial purposes) or for use in litigation.

(3) Whether the use is for proceedings in the United Kingdom or abroad.

(4) If it is for legal proceedings abroad, whether the use is in aid of civil or criminal proceedings.

(5) If the satellite proceedings are civil whether a significant disadvantage would be caused, such as requiring confidential documents to be made public when under English procedure these would not otherwise be made public.

24. There are additional considerations which need to be taken into account where the documents are proposed to be used in foreign proceedings:

(1) The court must presume in the case of Council of Europe states, absent cogent evidence to the contrary, that the foreign court will ensure that its proceedings are used fairly and therefore that there is no risk of injustice: AG for Gibraltar v May [1999] 1 WLR 998; Marlwood Commercial Inc v Kozeny [2005] 1 WLR 104 (CA) at [45]; Rottmann v Brittain [2010] 1 WLR 67 at [16]; Snoras (in Bankruptcy) v Antonov [2013] EWHC 131 (Comm) at [76].

(2) Where the use is to obtain legal advice from foreign lawyers, not to allow such a course would represent a “very drastic restriction on that party’s ordinary rights” and would almost be “contrary to the rule of law”: Tchenguiz v Director of the Serious Fraud Office [2014] EWHC 1315 Eder J at [20].

25. I will consider in due course how these principles apply to this application. It is worth observing, at this stage, that the particular aspects of the application in this case that merit noting are:

(1) The application relates to the use of documents in legal proceedings in Belgium. They are not for wider use. Use in legal proceedings in Belgium with its built-in safeguards is quite different to wider use, such as use by the press.

(2) The court is able to presume, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, that the Belgian Court will adopt a procedure that is fair to both parties if permission to use documents disclosed in this claim is given and the documents are relied upon.

(3) Although the Sandoz Defendants say the position was not made out clearly in the application and evidence in support, the permission sought is to obtain advice in the first instance and, only if advised appropriately, to adduce the documents.

(4) It seems to me that the court must presume that where, as here, the application is in the first instance for the documents to be reviewed by the second claimant’s lawyers in Belgium, that the lawyers will act properly and not seek to introduce documents in Belgian proceedings in a manner that we would regard as an abuse of the court’s process, such as by overloading the Belgian Claim with documents of marginal significance. They will act as a professional filter having regard to the normal approach to litigation in their jurisdiction.

(5) The Belgian Claim proceeds under harmonised EU law as set out in the Trade Mark Directive. It follows that the English court is in a better position to consider initial relevance of the documents to the issues in the Belgian Claim than would be the case were the claim to be one brought under domestic Belgian law.

(6) There are two distinct strands to the application. First, the claimants say that the documents merit being introduced in the Belgian Claim because they correct factual misstatements and disprove arguments put forward by Sandoz Belgium. Secondly, the second claimant wishes to obtain advice and if appropriate use the documents to bring fresh proceedings against the second to seventh defendants (or some of them) in Belgium. There may be a difference in the way in which the two strands of the claim are approached.

(7) Although an application is not made under CPR 31.22(1)(a), some of the documents have been referred to in a witness statement that has been read by the court at an earlier hearing. It is suggested that this is a factor that may affect the exercise of the court’s discretion.

(8) Issues of confidentiality are in play. An order setting up a confidentiality club has been agreed and approved by the court to deal with the claim for confidentiality asserted by the Sandoz Defendants in respect of some of the documents they have disclosed. The claimants have taken a practical view about agreeing to this order, and to pro tem confidentiality orders made at hearings where documents have been referred to. Certain passages in witness statements that refer to documents said by the Sandoz Defendants to be confidential, have been marked in red in the margins. No determination has been made about confidentiality and at the trial it is unlikely that confidentiality will be preserved.

(9) Had the trial date not been adjourned from October 2018, the trial of the claim would have taken place by now and it is likely many of the documents the second claimant wishes to rely on would have become unrestricted by virtue of CPR 31.22(1)(a).

26. Before setting out the issues between the parties in the Belgian Claim and considering the degree of overlap between the two claims, it is necessary to make some introductory remarks about how this application was dealt with in view of the fact that the request is for permission to use multiple documents. The initial application was for permission to use over 100 documents. On the first day of the hearing, I expressed the view that the court would need to review each of the documents for their relevance to the Belgian Claim, unless they could be put in classes and samples in each class reviewed. The hearing was adjourned part heard to enable the claimants to consider their position. The outcome of the review was that although Mr Hickman maintained his submission that the court was not required to consider each document, two changes were made to the application. First, the number of documents for which permission was sought was reduced to 51. The claimants produced a set of those documents with redactions to remove irrelevant material on 2 November 2018 in two document bundles. Secondly, the claimants provided a document that I will describe as a ‘Relevance Schedule’. It described each of the 51 documents and provided reasons in summary form why each was needed in the Belgian Claim.

27. For my part, I do not see how the court can deal with an application such as this one without reviewing each document, unless the parties have agreed upon an alternative approach, such as reviewing a sample. When reviewing an individual document, the court will, of course bear in mind that individual documents may have greater relevance or weight (or both) when seen in the light of other documents.

28. The sampling approach is more obviously suitable where the documents are an homogenous class. However, where, as here, the documents are sought to be used for one of two distinct uses and there are nine different reasons for relevance put forward by the claimants (with each document said to be relevant for one or more different reasons), individual review is the only option. This is potentially very time consuming and it was helpful that the claimants halved the number of documents the court had to consider.

29. It seems to me that where the court is asked for permission to use documents in foreign proceedings, it is not necessary for the court to do more than consider whether the documents are likely to be of relevance to the foreign proceedings. It is not for the court to determine whether the documents will, in fact, be thought to be sufficiently important to warrant introduction in the foreign claim by the foreign lawyers who review them, or that the foreign court will find them to be sufficiently compelling to give them weight in that court’s determination. This is so for largely pragmatic reasons. ‘Likely relevance’ is an initial threshold following which the court will wish to consider the broader issues that are to be derived from the authorities, namely whether there are special circumstances that provide cogent reasons why permission should be given.

30. The Belgian Claim has been summarised in the evidence of Mr Dekoninck to which I have already made reference, Mr Bruno Vandermeulen of Bird & Bird LLP in Brussels and Ms Florence Verhoestrate a partner with NautaDutilh BVBA/SPRL in Brussels. Mr Vandermeulen’s evidence is of limited assistance. He is an independent lawyer and has no first-hand knowledge of the claim. Unfortunately, he had not been provided with the Belgium Claim documents and, therefore, was not able to provide an accurate summary of the issues in that claim. He wrongly states that documents showing the reasons why the Sandoz Defendants chose the purple shades used in the AirFulSal Forspiro are not relevant to the Belgian Claim. He does however accept that the Belgian courts refer to IP decisions in other jurisdictions and that the decision of this court in this claim will be admissible in the Belgian Claim. Thus, to the extent that the judgment of this court refers to the disclosure documents, the Belgian Court will have regard to them, assuming of course that the judgment is handed down before the Belgian court makes its determination.

31. Mr Dekoninck’s witness statement focuses on issues concerning the validity of the mono-colour trade mark and infringement and contends that the intention of the parties “is in general irrelevant”. It was left to Ms Verhoestraete to point out that the counterclaim includes a claim for unfair advantage. Such a claim requires the court to have regard to whether there was an intention to ‘ride on the coat tails’ of the mark with a reputation. My attention was drawn to the passage in the judgment of Arnold J in Red Bull GMBH v Sun Mark Ltd and others [2012] EWHC 1929 (Ch) [94] to [96] where he reviews the decision of the CJEU in L’Oreal v Bellure and other authorities. It seems to me that for the purposes of this application, and contrary to the evidence of the Sandoz Defendants, I must proceed on the basis that evidence showing the state of mind of the Sandoz Defendants in choosing the colour purple for the AirFluSal Forspiro product is potentially of relevance to the Belgian Claim.

32. Mr Dekoninck makes two further points that warrant mentioning. He says:

(1) “15. It should be noted that under normal circumstances internal company documents would never have been accessible to the Second Claimant, nor invoked in Belgian proceedings. Unlike UK or Irish courts, which are familiar with discovery or disclosure procedures, Belgian courts are not familiar with this procedure and would consider these documents differently (i.e. most probably more literally, without taking into account the context) than a UK or Irish court, which is used to considering such internal documents in the specific context from which they originate, including a party selectively choosing to rely on just a handful of documents from the many disclosed by the other party.”

(2) “18. … the Second Claimant only filed the Benelux mono-colour trademark on 30 June 2015. We argue that Sandoz Belgium - prior to that date -could not know that the Second Claimant intended to file a Benelux mono-colour trademark and that it would try to enforce this mono-colour against various other shades of purple.”

33. There was at one time an issue between the parties about the maintenance of confidentiality if documents disclosed in these proceedings were permitted to be used in the Belgian Claim. It is now common ground that the court file in Belgium is not open to the public and that is open to the parties to agree a contractual confidentiality regime. The second claimant has offered to enter into such a regime and it seems to me it cannot seriously be contended that a contractual regime, albeit one that it is not subject to the court supervision and the ultimate sanction of contempt, is materially less satisfactory than the type of regime which would be applicable in this jurisdiction.

34. Evidence in support of the application has been provided in the 10th and 16th witness statements of Mr Eifion Morris, a partner in Stephenson Harwood LLP, on behalf of the claimants and the 10 th witness statement of Mr Marcus Collins, a senior associate at White & Case LLP, on behalf of the Sandoz Defendants. I have had regard to their evidence, but it is unnecessary to refer to it in detail.

35. I shall now explain how the Relevance Schedule is set out. It is divided into six components:

(1) Open documents that are referred to in Mr Morris’ 9 th statement (“Morris 9”).

(2) Open documents that are referred to in Mr Morris’ 10 th statement (“Morris 10”).

(3) Closed documents that are referred to in Morris 9.

(4) Closed documents that are referred to in Morris 10.

(5) Open documents that are referred to in Mr Morris’ 7 th statement (“Morris 7”)

(6) Closed documents that are referred to in Morris 7.

36. Open documents are not subject to the agreed confidentiality club or pro tem confidentiality orders. Closed documents are subject to that regime.

37. Morris 7 was made in connection with the claimants’ application to join the 5 th to 7 th defendants; the application that was heard by Mr Rosen QC on 3 July 2018. It referred to and exhibited a number of documents in making out a case that the court should make an order for joinder.

38. Morris 9 was made in support of an application to use documents disclosed in these proceedings for the purposes of related proceedings in the Republic of Ireland. They comprised documents forming exhibits to Morris 7 and additional documents. The claim in Ireland is, like this claim, based on the tort of passing off and the application to use the documents was agreed. The Sandoz Defendants say that it is quite different, on the one hand, to use disclosure documents where the cause of action is almost precisely the same to, on the other hand, use documents where the cause of action and the approach of the court toward the use of disclosure documents is quite different. In any event, it seems to me the fact that the Sandoz Defendants’ agreement to documents being used in Ireland carries little or no weight when the court considers the application of the relevant principles in this application.

39. As I have indicated Morris 10 is the statement made in support of this application.

40. Each of the documents listed in the relevance schedule is given a unique exhibit number and the Bates number allocated to the document in the Sandoz Defendants’ disclosure is also provided. For convenience and clarity, I will refer to the exhibit number when referring to an individual document.

41. There are nine relevance categories. The order in which they are listed is not indicative of the importance or weight that attaches to each category.

(1) Colour code

(2) Colour purple distinctive of Seretide

(3) Colour purple used by Sandoz as a trade mark

(4) Sandoz’ knowledge of GSK’s rights

(5) Sandoz’ coordination with its parent company Novartis

(6) Unfair advantage

(7) Public policy – not enough colours

(8) Difficulty in Sandoz changing colours from purple to another colour

(9) Evidence of the involvement of other companies

42. It is necessary to consider each of these points, although there is some overlap between them. The correct approach, in my judgment, is to form a view at a relatively high level about whether each of these issues is material to the Belgian Claim. If in any case the issue does not arise in the Belgian Claim, or is peripheral to it, it should be disregarded. If, however, it is clear that the issue is at least arguably engaged in the Belgian Claim, it is then necessary to consider whether any of the documents are likely to be relevant to the Belgian Claim in response to one or more of the relevance issues.

(1) Colour code

43. Sandoz Belgium contends in the Belgian Claim that the colour purple reflects the active pharmaceutical ingredients and an industry colour convention; this can be seen from paragraphs 17 to 21, and 90 to 98 (and footnote 74) of Sandoz’ Appeal Brief. It is said the choice of the colour purple was dictated by these considerations. At paragraph 21 of the Brief, as part of the Conclusion, it is stated that:

“It is clear from the above that colours used on inhalers for the treatment of asthma and COPD are mainly descriptive because they have a functional role in identifying or distinguishing the active pharmaceutical ingredient and the strength thereof. These colours indeed indicate the nature and strength of the product. Patients and health professionals rely on these colours when using or explaining the use of such inhalers. The importance of a colour-coded asthma treatment in patient education is indeed internationally well accepted…”.

The claimants say that when the colour purple was chosen for the Sandoz product, Sandoz had global colour rules and had they been applied the active ingredients in the AirFluSal Forspiro would have been shown using blue. It is clear that the issue about an alleged deviation from Sandoz’ own colour convention is equally relevant to packaging as it is to the device. Thus, documents said to be relevant to Sandoz’ colour code for packaging are potentially relevant to the Belgian Claim.

(2) The colour purple is distinctive of Seretide

44. The Sandoz Defendants deny that the colour purple is distinctive of Seretide or that it has brand identity with Seretide.

45. Mr Howe refers to the decision in Oberbank AG v Deutsher Sparkassen und Giroverband eV Joined Cases C-217/13, C-218/13 ECLI: EU:C: 2014:2014 and points out it is necessary to show not just brand association with a product but also that the colour is a badge of trade origin. Since the claimants’ product was the only one on the market for many years it is unsurprising that surveys contain spontaneous references to Seretide. I consider that the studies resulting from surveys and focus groups the second claimant wishes to rely on are likely to be treated with caution in the Belgian Claim. The findings on a survey that does not include any of the Benelux countries or is from an earlier period may not be regarded as providing assistance. That said, Sandoz Belgium’s Appeal Brief refers to proceedings in other countries and Mr Vandermeulen, who provides evidence for the Sandoz Defendants, says the Belgian Court, may refer to the decision of the English court in this claim. On balance it seems to me that this court should be slow to filter out material that may be thought to be important by the second claimant’s Belgian lawyers. The Belgian court may or may not agree with them; but that is not to the point.

(3) Colour purple used by Sandoz as a trade mark

46. Documents are said to show that purple is used by Sandoz as a trade mark and as a key component in its branding. Paragraph 124 of the Sandoz Belgium Appeal Brief asserts that Sandoz does not use the colour purple to distinguish the AirFluSal Forspiro product. It goes on:

“The use of another shade of purple, in combination with white on the inhaler and its packaging by Sandoz is indeed only an indication of the characteristics of the product. This indication refers to the fact that [the product] is a combination product, in accordance with the informal colour practice for medicinal products for the treatment of COPD/Asthma.”

Documents that may show Sandoz used the colour purple as a trade mark, or which might tend to contradict or cast doubt on the assertion I have quoted from the Appeal Brief, or other similar statements, are likely to be relevant to the Belgian Claim.

(4) Sandoz’ knowledge of GSK’s rights

Mr Hickman submits that documents showing Sandoz’ knowledge of the risk of infringement and a decision to take that risk are relevant to the ‘riding on the coat tails’ issue in the unfair advantage claim, and that Sandoz was on notice of any trademark issues concerning the colour purple, are relevant. Mr Howe submits that it is obvious Sandoz, as a generic drug producer, would have in mind the rights asserted by Glaxo. Until it was declared invalid, Sandoz would have had in mind the Community Trade Mark that was declared invalid in this claim.

(5) Coordination with Novartis

47. The extent to which Novartis does not conform to colour codes is said to be in issue. However, the assertion made in footnote 76 to paragraph [99] of the Appeal Brief – “Sandoz is in no way involved in Novartis’ business, let alone their choice of colours” – is not an issue of any real significance in the Belgian Claim. It is only relied on in relation to one document along with other relevance issues.

(6) Unfair advantage

48. I have already referred to the decision in L’Oreal v Bellure and the possibility that documents showing how Sandoz went about the production of a generic product, and its choice of colour, could be relevant. It is right that the unfair advantage claim by the second claimant is subsidiary to the main thrust of its counterclaim. That however is not a relevant consideration when considering likely relevance for the purposes of this application. It may that be that in light of consideration of the documents the second claimant wishes to use, the unfair advantage claim will assume a greater prominence. It is legitimate for the second claimant’s lawyers in Belgium to consider and advise upon use of documents of this relevance type.

(7) Public policy: not enough colours

49. Sandoz Belgium sets out submissions at paragraphs [110] to [114] in its Appeal Brief under the heading: “The colour trade mark of Glaxo is contrary to the public interest in view of the specific circumstances of the case”. The case is developed at paragraph [111] and submissions are made about the limited availability of the basic colours for asthma and COPD inhalers “… in view of the fact that several colours are already used by many actors (only 12 basic colours can be distinguished and less than 5 would remain free) and, on the other hand, to the descriptive character of colours, which therefore must remain freely available to anyone. The availability of these descriptive signs should not be unduly limited for other market players offering the same types of goods …”. There is a public policy issue which is live in the Appeal and to the extent there are documents which contradict or weaken the case put forward by Sandoz Belgium, they are likely to be relevant.

(8) Difficulty in changing colour

50. The case put forward by Sandoz Belgium in its Appeal brief at paragraph [154] is to the effect that if the second claimant is able to enforce the mono-colour Benelux mark, it would be abusing its dominant position and Sandoz Belgium would have to redesign the AirFluSal Forspiro product. “This would result in the need to redevelop and remanufacture the new products and to obtain new marketing authorisation.” Documents showing how difficult or easy it is to re-manufacture the product have potential relevance. The position is not as Mr Howe submitted that obtaining new marketing authorisation is the only factor that may cause delay in gaining entry to the market.

(9) Evidence of involvement of other companies

51. The claimants say they wish to consider bringing a claim against new parties in Belgium. It is suggested that there could be no entitlement to do so. Mr Howe submits that (a) the involvement of other parties in the development of the Sandoz product is well known and the second claimant does not need the documents upon which it wishes to rely to obtain advice and bring a claim and (b) in reality, from a commercial perspective, there is little reason why the claimants might wish to do so. As to (a), it is not for the Sandoz Defendants to decide which documents the second defendant may need. That is a matter for the second defendant’s lawyers. As to (b), similarly, the second claimant is entitled to seek advice about steps it may wish to take and, if there are documents that are likely to be relevant to that issue, they should not be ruled out at the initial relevancy stage. Documents such as the contractual arrangements between Sandoz and Vectura, from which the financial arrangements have already been redacted, are plainly relevant to issue of Vectura’s involvement.

52. As I have indicated, the relevance criteria overlap and most of the documents which the second claimant wishes to use are said to be relevant by reference to more than one of the relevance criteria. My conclusion is that with the exception of issue (5) all the issues are helpful markers of relevance.

53. It is not proportionate to give reasons for accepting relevance for each document individually. My conclusion, having reviewed the Relevance Schedule and documents themselves, is that all the documents the second claimant wishes to use are likely to be relevant to the Belgian Claim apart from documents with exhibit numbers 58, 60, 99, 152, 162, 164, 165, 169.

54. The application is limited to a request for permission to use the documents applying the power under CPR 31.22(1)(b). There is no application for a declaration that particular documents have been “read to or by the court, or referred to, at a hearing which has been held in public”. Mr Hickman submits that the use of the documents exhibited to Morris 7 in open court is a powerful factor in relation to an application for permission to use them. He does not, however, seek to argue that an exhibit is for these purposes part of the witness statement to the effect that by reading the witness statement the court is deemed to have read the exhibits.

55. The documents exhibited to Morris 7 were provided to the court in order to make the case that the Vectura defendants were involved. It could not be suggested that their use was in any way gratuitous. The authorities concerning the use of documents in court have recently been considered by the Court of Appeal in Cape Intermediate Holdings Ltd v Dring [2018] EWCA Civ 1795. I need only refer to paragraphs [103] to [109]. Documents that the court was asked to read outside court will be deemed to have been read unless it can be established to the contrary. It is clear from the skeleton arguments that were filed in advance of the hearing before Mr Rosen QC that he was asked to read the witness statements, but not the exhibits, and it can be presumed that he did that. The text of Morris 7 itself refers extensively to the documents that formed the exhibits, sometimes citing extracts from them. It follows that although the exhibits themselves will not be treated as being read out in in open court, they have been extensively considered at a hearing in open court. A limited number of documents were subject the confidentiality club order and a pro tem confidentiality order that covered the hearing, but the majority were not confidential. I agree with Mr Hickman that use of the Morris 7 documents for the joinder application is a factor the court should take into account on an application under CPR 31.22(1)(b) whilst being careful not to conflate the test under 31.22(1)(a) with the test under 31.22(1)(b).

56. Similar considerations do not apply to the documents that are exhibited to Morris 9 or 10.

57. The principal additional submissions Mr Hickman puts forward can be summarised briefly:

(1) The proposed use of the documents is for legal advice and litigation and not some wider use. The second claimant has professional advisers who will in the first instance consider the documents and advise about their proposed use. The English court is entitled to assume that they will act in a professional way and the English Court is entitled to presume that the Belgian Court will act fairly and only rely on the material when it is just and fair to do so.

(2) The documents (apart from those I have ruled out of account) are likely to be of relevance to the Belgian Claim. Whether they will be deployed will be a matter for the second claimant’s lawyers in Belgium and whether they are in fact material to the claim will be ruled upon by the Belgian Court.

(3) There is no injustice, or at least no significant injustice, to the Sandoz Defendants. It is no longer suggested that there are material risks to the confidentiality of the documents, where that is relevant. The court file is not open and the second claimant offers to enter into a confidentiality club which will have contractual force. The absence of enforcement by way of proceedings for contempt is, in the context of these parties, a point of no real substance.

58. Mr Howe submits that the English court should be slow to permit a party to use documents obtained in proceedings in England under our disclosure procedures in a foreign claim where disclosure of a company’s internal documents will only very rarely be permitted. I can see the force of this submission if it can be suggested that a claim was brought in England for the principal purpose of obtaining disclosure and using it elsewhere. However, that could not be said of this claim. At the time it was was commenced, the claimants were seeking to enforce their Community Trade Mark within this territory. The proceedings now proceed relying on the domestic remedy of passing off. To my mind, the limited nature of disclosure in the Belgian Court is a factor of limited weight. It has the effect that an English court might be more circumspect about the Belgian Claim being flooded with a large volume of documents. The application is now limited to a relatively small number of documents and the basis for the use of each document has been carefully explained.

59. There is more force in Mr Howe’s submission that the court should be concerned about the claimants ‘cherry picking’ documents from disclosure in this claim and using them out of context. This might have the effect of forcing Sandoz Belgium to review a large number of documents and being required to submit a disproportionate volume of documents to correct false impressions created by disclosure documents that have been taken out of context. Mr Howe also submits that the difference of approach to the conduct of claims between England and Belgium is a material factor. He points out that in England, documents are often explained and given life in the course of cross-examination. Documents which tend to point in one direction can be explained and put in a proper context. In Belgium, although the hearing of the appeal will involve oral submissions based upon the written briefs, there will be no witness evidence to provide necessary illumination to the documents.

Conclusions

60. The court is required to balance the competing interests of justice. On the one hand there is an interest in permitting the second claimant to use documents in the Belgian Claim and to consider bringing fresh proceedings in Belgium and on the other hand in preventing injustice to the Sandoz Defendants and Sandoz Belgium. The claimants must be able to satisfy the court there are special circumstances which constitute special reasons for permitting collateral use. In my judgment, the claimants are well able to meet this test, with the corollary that the balance of justice comes down firmly in their favour. My reasons are:

(1) The parties to this claim, and associated companies, are engaged in litigation on a very wide scale in many jurisdictions. They are part of very substantial businesses with equal resources. There is no suggestion that the application is oppressive.

(2) Although the legal basis for this claim and the Belgian Claim are markedly different, there are similarities between some of the issues that are engaged.

(3) The claimants have been able to satisfy the court that the majority of the documents they seek to use are likely to be relevant to the Belgian Claim. The interests of justice would therefore militate in favour of the claimants having an opportunity to obtain advice about their use in the Belgian Claim.

(4) Use of the documents to enable the second claimant to consider whether, having obtained advice, a claim against additional parties should be pursued is, to my mind, more compelling than use of documents in connection with the Belgian Claim. There are no risks of adversely affecting the existing proceedings. The court should be slow to stand in the way of a party who wishes to obtain advice about pursuing a lawful course of action.

(5) There is now an agreed procedure for the orderly progress of the appeal in Brussels with the second claimant filing an additional brief followed by Sandoz Belgium. The disruption, if any, by the introduction of additional documents has been minimised.

(6) The number of documents the claimants seek to use is relatively small. Those that may be used in the Belgian Claim are not disproportionate in volume to what is at stake in those proceedings. There is no real danger that the Belgian Claim will be overwhelmed with additional documents even if all of them are deployed and Sandoz Belgium considers it is necessary to file additional documents to counter documents having been ‘cherry picked’ by the claimants.

(7) The difference of approach between litigation in England and Belgium is a factor, but one of limited weight. There is no suggestion that the use of documents obtained in disclosure is an abuse of this court’s process. The risk of the Belgian Court’s process being subverted by the introduction of disclosure documents is marginal, particularly bearing in mind the involvement of the Belgian lawyers and the procedure that has been agreed.

(8) I accept Mr Hickman’s submission in relation to the documents exhibited to Morris 7. The documents that are exhibited were extensively discussed in the witness statement which was read by the Deputy Judge. Although the claimants do not make an application for a declaration that they are permitted to use those documents as of right, the documents have been legitimately deployed for the purposes of an application heard in open court (subject only to the pro tem confidentiality order).

(9) It is not open to the Sandoz Defendants to say, and they have not submitted, that if the order permitting use of the documents is made, their position in the Belgian Claim is prejudiced, in the sense that the likelihood of them successfully prosecuting the claim and/or defending the counterclaim is reduced. The interests of justice require that material which is likely to be relevant should be permitted for proper purposes. A reduction in their prospects of success is an immaterial consideration in their favour and, if anything, it weighs in the balance in favour of the claimants.

61. I will make an order permitting the second claimant to use the redacted documents included in the two document bundles that were produced on 2 November 2018, other than those that I have excluded.