An Overview of the Design and Engineering

The hydrofoil is a removeable part, principally made of carbon fibre reinforced plastic, projecting from the side of the boat. The V1 port foil can be seen on the Boat in the photograph at page 3 of a document within the trial bundle called ATR T2 Foil Timeline at 628/610. It is described by Mr Smith as being similar to a springboard.

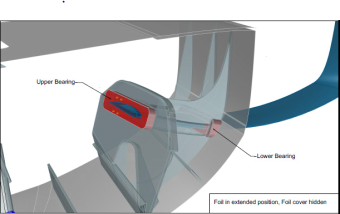

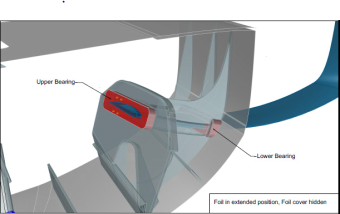

The foil is attached to the boat via two bearings, the upper bearing inside the boat and the lower bearing in the hull shell. Mr Smith illustrates this at paragraph 5.4 of his report at 552/534.

The foil is attached to the boat via two bearings, the upper bearing inside the boat and the lower bearing in the hull shell. Mr Smith illustrates this at paragraph 5.4 of his report at 552/534.

As indicated above, the purpose of the foil is to create lift so as to enhance the performance of the Boat. In so doing, the foil bends and considerable compressive and tensile forces come in to play. The surface of the foil in the photograph at paragraph 36 above which is on the upper side (where the foil runs horizontally) and the inboard side (where the foil curves through to the vertical) is that which takes the preponderance of the compressive force, whereas the lower and outboard surface takes the tensile force.

As indicated above, the purpose of the foil is to create lift so as to enhance the performance of the Boat. In so doing, the foil bends and considerable compressive and tensile forces come in to play. The surface of the foil in the photograph at paragraph 36 above which is on the upper side (where the foil runs horizontally) and the inboard side (where the foil curves through to the vertical) is that which takes the preponderance of the compressive force, whereas the lower and outboard surface takes the tensile force.

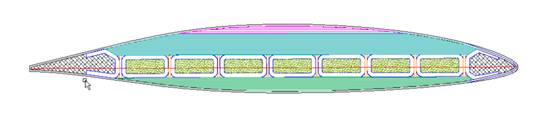

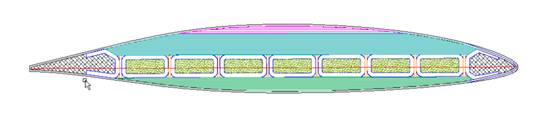

The broad design of the hydrofoil can be seen from this cross-section, which appears at paragraph 5.3 of Mr Smith's report, again at 552/534.

The top of this diagram equates to the upper and inboard surface of the photograph above taking compressive force and hence is described at times as the compression side. Correspondingly the bottom is that taking the greatest tensile forces and is called the tension side. The leading edge, that which is nearest the front of the boat, is to the right and the trailing edge to the left.

The construction is described at paragraph 5.3 of the report of Mr Smith, cross referring to the diagram at paragraph 39 above, as comprising an outer (white) skin within which there is on the compression side, a so-called unidirectional plank (shown in magenta and cyan here) and on the tension side a unidirectional plank shown in green. The unidirectional planks comprise laminate layers of carbon fibre which has been pre-impregnated with a resin. (The pre-impregnated layers are called, at times, "pre-preg"). The term "unidirectional" reflects the fact that fibres in the laminate run in one direction. The manufacturing process is described further below.

Between the two planks is an area in the centre comprising so-called "shear boxes" (alternatively sometimes called "webs"), depicted as white rectangles (representing carbon fibre plies) wrapped around a khaki core that was made of Rohacell, a type of foam. The use of foam is intended to lighten the whole hydrofoil but the foam on its own is not sufficiently strong to resist the shearing force to which it would be subject. The purpose of the shear boxes is to resist the shearing forces caused by the stretching and compression of the layers in the structure as a result of the foil bending. The specification, which appears at 985/950 required that 4 of the 16 plies (25%) be laid in an 0° orientation and 12 of them (75%) be laid at a 45° angle.

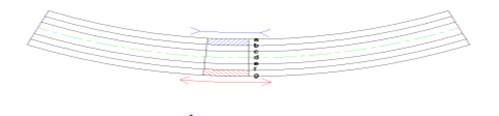

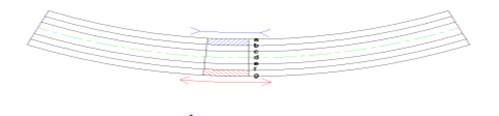

Mr Smith explains the compression, tensile and stress forces in a laminated beam of the nature of the foil by way of the upper diagram at paragraph 4.4.9 of his report, (549/531) where the top part of the diagram represents the compression side of the foil and the bottom the tension side.

(The seven layers shown are lettered in black from a to g, though it is not easy to make this out.)

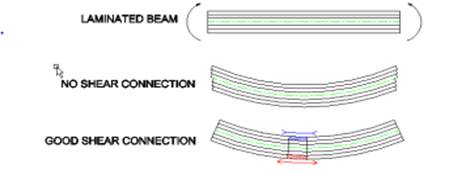

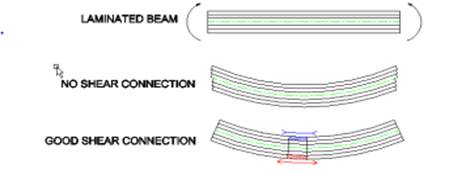

The force created by bending of the beam, known as interlaminar shear stress, will tend to cause interlaminar shear (in other words separation of the layers) unless there is good shear connection. This is illustrated by Mr Smith at paragraph 4.4.6 of his report (548/530).

With no shear connection, one can see how the laminates tend to debond creating a ragged end of separate layers, whereas with good shear connection, the laminates stay bonded in a neat line. The capacity of the material to do this is called inter-laminar shear strength.

Four points are of particular note:

(a) The compressive force is greatest on upper side of the foil (letter a in the diagram referred to at paragraph 43 above);

(b) The tensile forces are greatest on the lower side (letter g);

(c) The compressive and tensile forces reduce as one moves from the outer surface to the middle, such that, at a point known as the neutral axis (letter d above), both forces are zero;

(d) The shear forces are maximum at the neutral axis.

At paragraph 4.2 of his report, Mr Smith explains how good shear connection is achieved in a structure made of a composite such as carbon fibre reinforced plastic so as to resist the effect of the compressive forces:

"4.2.3 A laminate is composed of fibres and matrix. We could start by thinking of the fibres as being like a ponytail and the matrix as a strong hair-gel.

4.2.4 If we want to carry a load in tension, say lifting a bucket out of a well, we could cut off the ponytail, attach our load to each end then pull. The load we could carry would be proportional to the number of hairs, and aside from the difficulty of attaching the load to the ends of the hairs, we wouldn't really need a matrix to contribute to the tensile strength - each hair would take its share of the tensile load.

4.2.5 If on the other we want to carry a load in compression, as in the case of a table leg, the bundle of hairs would be no use at all as individual strands would buckle and collapse. Gluing the hairs together with gel (like a punk spike hairstyle), would resist the tendency of the individual hairs to buckle and increase the capacity of a given bundle to resist compressive loads. If the matrix properly bonds to each strand and there are sufficient hairs in the bundle we could make a table leg capable of supporting the top and whatever is on it. The matrix is therefore important for compressive strength."

Mr Smith explains how the interlaminar shear strength depends both on the strength of the matrix itself and the matrix to fibre bond strength. Bond strength may be affected by the ratio of resin to fibres, since if there is too much resin, the matrix will tend to carry the shear load and if there is too little, dry fibres may lie next to each other with no shear load carrying capacity. Contaminants may also reduce the binding between layers. The processes of de-bulking, described below, contributes by avoiding air becoming trapped between layers.

One issue with hydrofoils is a tendency for what is called ventilation, that is to say the drawing in of air onto the surface of the foil as it cuts through the water. Mr Thomson explained that ventilation slows the boat and reduces the capacity of the foil to lift it out of the water. Mr Thomson became aware that an adjustment of the shape of foils by the use of what has been called a 'camel toe' detail had been tried during the America's Cup (another well-known yachting race) and was thought to be successful in reducing ventilation and thereby enhancing performance. He raised this with the designers, Guillaume Verdier and VPLP, and they came up with an adaption to the leading edge of the V1, involving the manufacture of a separate moulded component which was then bonded onto the leading edge of the main foil. The 'camel toe' name arises from the series of notches or grooves in the leading edge of the moulded component.

The purpose of the V2 design was to accommodate the camel toe feature and to improve on performance from the V1 foils. There was debate during cross examination as to the extent to which the V2 design was experimental. Mr Thomson did not accept this to be so, saying simply that the design changes were intended to improve the ventilation effect without affecting reliability or safety.

The result of the change to the camel toe feature was a difference in profile of the foils. Mr Thomson compared the V1 at figure 24 on 715/697 with the V2 at 714/696. (It should be noted that the upper skin is on the bottom on the V2 but the top on the V1 indicating that they are in opposite orientation). In any event, the point made by Mr Thomson is that the thickest part of the foil is further forward in the V1 than in the V2, this having been moved rearward to accommodate the recess with the camel toe on the V2.

Events on the Solent in September 2016

The port V2 hydrofoil was collected by the Defendant from the Claimant's premises on 27 August 2016. Testing began on 1 September 2016.

Mr Thomson states that there were three objectives to the testing:

(a) To test the bearing mechanism, including the deployment and retraction of the foil;

(b) To test the fit, adjustment and operation of the foil under increasing load;

(c) To test the performance of the foil, in particular the optimal angle of attack.

The testing involved people both on board the boat and on land carrying out a variety of observations and measurements.

On 1 September 2016, the wind is stated by Mr Thomson to have been 13-17 knots, a moderate breeze. The foil was tested to a maximum load of 12.5 tons.

On 2 September 2016, the wind was a little brisker, 16 to 22 knots, described as a fresh breeze. A maximum load of 12.9 tons was recorded. Mr Thomson describes how, when the boat was close to the end of a test run, a loud bang was heard. This led to the boat returning to land and being checked over, but no defect was identified, whether in the foils or elsewhere.

On 3 September 2016, the wind was stronger again, 20 to 25 knots which is described as a strong breeze. They found flat water between Cowes and Beaulieu and started to do upwind and downwind tests, travelling upwind to Beaulieu and downwind to Cowes. Mr Thomson describes what happened thereafter in paragraph 9 of his witness statement:

"On our third run the foil angle of attack was changed from 2.8° to 3.8° and boat was sailing at around 26 knots downwind when there was a huge bang and the boat heeled violently. The helmsman reacted very quickly and turned the boat downwind and the boat slowed. When deployed the foil curves out from the side of the boat. Looking over the side of the boat we could immediately see the foil had broken. It was not completely separated but it was hinging up and down at the break point. We managed to get a halyard on the end of the foil to support it clear of the water and returned to port. The load cell was averaging 11.5 tons and reached its maximum reading of 13 tonnes when the foil broke."

In the following paragraph, Mr Thomson goes on to comment on the load cell measurements:

"The load pins that were measuring the load in the foil were working and recording what I believe to be accurate loads. The pins were supposed to be setup to read up to 16 tons, however there was a mistake and the limit during the testing was set at 13 tons. This meant that any load over 13 tons appeared as 13 tons. When we reinstalled the V1 foils the pins were set up to 16 tons. The data recorded during the 2016-2107 Vendée Globe shows that in only a few instances did the foil loads exceed the maximum reading of 16 tons. That was over the full length of the race during which all conditions were experienced from light to storm force winds and wave heights over 6m. Boat speeds in excess of 30 knots were experienced on numerous occasions."

In comparison with some of the more extreme weather and wind conditions that he has experienced, Mr Thomson describes the conditions in the few hours of testing before the foil broke as "extremely benign."

The delaminar failure of the foil can be seen in the photographs at 1228/1193 and 1229/1194. A crack is apparent in the compression plank. The consequent failure of the foil can be seen in the photographs at 1202/1167 to 1223/1188.

The Claimant's alleged losses

The Claimant's case is that it delivered the port foil to the Defendant in accordance with the contract and that it was ready and willing to deliver the starboard foil. However, the Defendant refused to pay the purchase price in accordance with its obligation under section 27 of the Sale of Goods Act 1979.

The Claimant contends that its recoverable losses are:

(a) The balance of the price originally agreed in the supply agreement, as set out at appendix 2 to that agreement, which the Claimant contends is £252,542; alternatively

(b) The balance of the payment price plus bonus as agreed in the discussions summarised at paragraph 31 above, which the Claimant contends is £92,480 together with the bonus of £30,000 to reflect Mr Thomson's second place in the 2016/2017 Vendée Globe; and in any event

(c) Storage charges in the sum of £35,600 relating to the hydrofoils which the Claimant contends are a contractual obligation pursuant to the terms of their invoices (see paragraph 33 of Mr Robinson's statement at 476/459).

The Claimant's argument that, notwithstanding the contractual variation referred to at paragraph 31 above, it is entitled to the purchase price on the basis agreed in the original contract is predicated on the argument that the variation agreement was subject to a condition precedent that the entirety of the purchase price be paid within two days of the agreement. This is drawn from paragraphs 18 and 19 of Mr Keogh's witness statement (440/423). There was no further elucidation of this issue in oral evidence.

In response, the Defendant contends:

(a) The Claimant is not entitled to payment for the hydrofoils because they were not in compliance with the contractual standard and as a result were worthless; alternatively

(b) If the Claimant is entitled to payment of the purchase price, the varied price referred to at paragraph 31 above was not the subject of any condition precedent and therefore the Claimant is entitled to the balance of that sum;

(c) The bonus depended upon the Defendant using the V2 hydrofoils in the Vendée Globe. Since they were not used, the Claimant has no entitlement to a bonus;

(d) Whilst the Defendant pleaded no case in respect of the storage charges, at trial, it argued that the Claimant was unable to show that any contractual terms was incorporated to the effect that storage charges were payable if the goods were not collected. It is incorrect for Mr Robinson to state that the invoices refer to storage charges. In fact, the invoices in the disclosure do not contain a term as to the payment of storage charges though the delivery notes do – compare for example the delivery note at 1515/1454 and the corresponding invoice at 1516/1455. There is no evidence (or indeed pleaded case) that the delivery notes created contractual terms, nor is it obvious how they would do. Further, the Claimant has not shown any trade practice or established course of dealing.

The Defendant's alleged losses

The Defendant's counterclaim is for the following losses:

(a) Diminution in value of the foils as a result of their substandard quality. The Defendant contends that they could not be used for the Vendée Globe, their primary purpose, and therefore are worthless. Accordingly it seeks to recover the element of the purchase price that was paid, £243,520 plus VAT.

(b) As a result of the Claimant's breach of contract, the Defendant contends that it suffered the various losses set put at paragraph 66 of the Amended Defence and Counterclaim (45/45), either as wasted expenditure on the manufacture of the V2s and modification of the Boat to accept them, or as consequential losses. Those items are:

| Engineering and studies for V2 hydrofoils and bearing designs |

£37,142 |

| Costs of changing the bearing system on the Boat to accept the V2 hydrofoils |

£38,430 |

| Modification to the Boat to accept the V2 hydrofoils |

£15,937 |

| Modification to the Boat to accept the V1 hydrofoils again |

£7,400 |

| Investigation and analysis by APD |

£5,600 |

| Investigations and analysis by Gurit |

£5,020 |

| Wasted costs of Mr Ryan Taylor |

£65,580 |

| Wasted costs of cancelling professional sailors due to broken hydrofoils |

£20,020 |

| Other costs |

£6,642 |

The evidence in support of the Defendant's losses is set out at paragraphs 44 to 48 of Mr Daniel's statement.

In addition to the matters set out above, Mr Daniel claims the costs of a third set of foils. The argument for the recovery of these costs is that, when the Defendant came to sell the Boat after the 2016-2017 Vendée Globe race, there were no available foils because the V2 had broken in the instant incident and the V1s had been damaged in the race itself. The Defendant contends that the boat would not have achieved the same value if it had been sold without foils.

Discussion 2: – the Expert Issues

In his closing submissions, Mr Land for the Defendant identified the expert evidence issue as being whether the manufacture by the Claimant of a foil in accordance with design drawings provided to it should have resulted in a foil that could withstand the interlaminar shear loading at 13.5mm that caused the failure of the hydrofoil had it been adequately constructed. This in my judgment is a reasonable way to put the central issue in the case. It might alternatively be put as to whether a failure by the Claimant properly to construct the hydrofoil in accordance with the specification provided to it was the cause of the failure. Either way, the burden of proving the cause of failure lies with the Defendant. This case has at times been put on the basis that the failure must have been caused either by a design failure or a manufacturing failure and they do seem to be the only plausible explanations, the question of "user error" being ruled out on the evidence.

On the Defendant's case, the alternative explanation to a manufacturing error, that there was some inadequacy of design, is untenable. It supposes either that the designer failed to have regard to the degrees of force to which the boat would be subject or that, as designed, the boat was not able to withstand the predicted forces. Both of these, it is said, can be rejected because:

(a) Mr Reis' modelling shows that the foil as designed is strong enough to resist 28 tonnes of force even at its weakest point.

(b) The failure of laminar bonding did not occur in the neutral axis, where shear forces would be at their maximum, but rather on the plane 13.5mm in from the outside of the unidirectional compression plank. This is some way from the neutral axis and therefore the failure would not have occurred here unless this was a weak point. Given that the forces are greatest at the neutral axis, if the failure at the 13.5mm plane was due to overloading, the load on the neutral axis at the time of failure would have been even greater. But since the unidirectional plank was designed to be uniform in construction, failure at a point other than that where the shear force is at its greatest leads overwhelming to the conclusion that the failure was due to a manufacturing or materials error at the point of failure rather than a more generalised design (or indeed construction) error.

Whilst Mr Smith is not able conclusively to state the cause of the manufacturing defect that led to failure, his main targets have been the use of DT124 in place of the Gurit product, the presence of contaminants and/or an inadequacy on the manufacturing process affecting the efficacy of the resin.

The Claimant's primary position, based on Mr Reis' FEA testing, is that the more probable cause is design error and specifically the assertion that the design of the joggle leads to a risk of interlaminar failure at 13.5mm. But the Claimant puts equal weight on its secondary case that the Defendant cannot prove that the failure was due to manufacturing error and therefore fails to discharge the burden of proof which lies on it.

In considering the expert evidence, I found both Mr Smith and Mr Reis to have relevant expertise to consider the complex issues that arose, though neither professed a thorough knowledge of all of the many and varied scientific processes that can be employed in investigating an incident of this nature. I reject any suggestion that Mr Reis gave evidence that was partisan or adversely affected by his prior relationship with the Claimant. At all times, it appeared to me that he was considering matters carefully on the basis of his expert knowledge rather than acting as a hired gun who simply said what suited the party who engaged him. As to Mr Smith, I found his evidence largely to be carefully given, with appropriate concessions where matters were outside his area of expertise. However, in one respect identified below, I found his evidence not to be reliable. Such unreliability flows in all probability from a firm belief (which may be correct) that something went wrong in the manufacturing process and that the court needs to focus on what the most probable failing in that respect was. However, for reasons set out below, that analysis fails in my judgment to deal with the alternative possibility that in fact the failure was not due to a manufacturing defect at all.

I turn to the three possible explanations proffered by Mr Smith as to the manufacturing defect.

As to the significance of the change of resin from a Gurit product to a Delta Technologies product, as indicated above, the available evidence indicates that both contained nano particulates. There is no evidence that DT124 performed in any less satisfactory way than the Gurit product. In any event, as the Claimant points out, the designers were consulted on the use of the different product and agreed to it. The Defendant has failed to formulate a case that shows how the use by the manufacturers of a product approved by the designers was a manufacturing defect for which the manufacturers were liable rather than a design defect, the Defendant accepting that design defects are not matter for which the manufacturers are liable.

As to contamination, Mr Smith raised the question of the presence of squalene as a contaminant that may have contributed to the failure. As indicated above, he was limited in the extent that he could rely on evidence as to its presence. It was also put to him that squalene occurs naturally in sea water, it being found in fish oil. He said that he had never known of squalene being blamed for the failure of a laminate like this and that in any event he could not deny that, if squalene were present within the damaged part, it may have resulted from that part being dragged through sea water.

In my judgment, the alleged presence of squalene cannot be blamed for the failure of the hydrofoil. Whilst its presence (if proved) could be consistent with contamination in the manufacturing process, it could equally be consistent with contamination after the board failed. In any event, the evidence as to its presence is equivocal. I reject this suggested cause of failure.

As to any other contamination being the cause of failure, the Defendant raises this as no more than a theoretical possibility. I see no evidence to convince me that it is more likely than not that some form of contamination caused a weakness in the foil.

Mr Smith's evidence, as accepted by Mr Reis, shows that it is probable that the shearing failure occurred at around 13.5mm into the compression board and that, since this is not the point at which the forces were greatest, one would not expect to have occurred there absent some design or manufacturing error that led to weakness there. But, when closely analysed, the evidence does not show that the failure was more probably than not due to manufacturing error.

In advance of trial, the only explanation for such defects that Mr Smith could proffer were that the weakness was caused by the use of DT124, contamination by squalene and/or some manufacturing weakness due to unidentified contamination or unidentified manufacturing error. Having rejected either the use of DT124 or squalene contamination this leaves only the Defendant with the difficulty of showing that that the weakness was due to a cause that it cannot identify but that must have been caused by or at least during the manufacturing process. In spite of considering a wealth of material, Mr Smith is unable to come up with any clear basis for showing that the weakness at 13.5mm was due to a manufacturing error.

The inference of a manufacturing defect comes in significant part from the evidence referred to at paragraph 97 above as to the compressive strength of the board. If reliable, that would be a strong pointer to a manufacturing or product defect. However, I accept Mr Reis' evidence that tests of compressive strength based on parts from the damaged board are potentially unreliable. On any version of the evidence, considerable energy was dissipated on the failure of the laminate and it is inevitable that this will have caused significant compromise of the structure.

Further, I accept Mr Reis' evidence that, at least at a theoretical level, the introduction of the camel toe feature may have compromised the strength of the board. The obvious weakness of this as an explanation for the actual failure of the board is that this compromise of the board supposed a load of 28 tonnes, far in excess of the probable load at the time of failure. Were there some plausible evidence of an identified manufacturing defect at the 13.5mm level, this would probably have been sufficient to persuade me that it was that rather than a design issue that was the cause of failure, since Mr Reis' theory as to the design weakness is dependent on evidence assuming far higher loads and therefore is improbable. But in the absence of any identified defect, the court has to balance the improbable explanation proffered by Mr Reis and the speculative explanations of Mr Smith. Ultimately, that leads to a position where, in my judgment, the Defendant is unable to discharge the burden of proof.

Mr Smith's evidence that the Pierrepoint NDT analysis and the electron microscopy performed by APD in fact shows manufacturing defects at this level has caused me to pause for thought in this analysis, even though this theory was first expounded in the witness box. Of course, the Claimant would be understandably concerned if the point on which the Defendant succeeded was one raised for the first time by its expert at the close of cross examination, without the Claimant's expert having had any opportunity to comment on the issue. But that is one of the hazards of litigation - sometimes it is only in the middle of a trial that the true picture emerges. The Claimant cannot (and in fairness does not) expect me to disregard the evidence simply because it had never been raised before.

However, I am not satisfied that I can place any weight on this evidence:

(a) Whilst Mr Smith had not seemingly seen the Pierrepoint analysis when he prepared his report, it would be surprising that, if he considered it to be significant, he only mentioned this for the first time in cross examination. Of course this may be because the significance of the analysis only came to him when giving evidence. But if this were so, I would be concerned that he had not fully thought through what he was saying.

(b) Moments before giving the evidence, relating to the Pierrepoint Report, Mr Smith had dismissed this kind of NDT testing as of little help in investigating the cause of the event. At the point that he made that statement, it is difficult to believe that he had in mind that he was about to say that the NDT in fact supported his interpretation of events. This adds to my anxiety about how carefully considered this evidence was.

(c) In any event, I am not clear that the Pierrepoint analysis has the importance that Mr Smith attributes to it. It is correct that the table at 893/875 identifies what may be anomalies in "P1", "P2 and "P3" at a depth of 12mm from the outboard surface. But, on my reading of the report, that is a reference to the points shown on picture 4 (894/876) and scans 3 and 4 (895/877), not the scan at 889/871, to which Mr Smith made reference. Without the kind of fuller investigation of this issue which would have occurred if the point had been made in advance in writing, thereby allowing the Claimant's expert to consider and comment upon it, I am not satisfied that Mr Smith is correctly interpreting the Pierrepoint report.

(d) If the APD investigation shows what Mr Smith contended in cross examination, I do not see why he failed to make the point within his original report. Mr Smith noted that report with its reference to failure at the 12mm level, but did not attribute any significance to the photograph which he now says demonstrates that his case is correct. Again, it has not been possible properly to investigate whether the photograph is being correctly interpreted by Mr Smith because the point had not been made earlier.

(e) The matters on which Mr Smith commented were not put to Mr Reis. One might wonder whether this was because Mr Land, for the Defendant, was unaware of the points until Mr Smith gave evidence, but that of course would be speculation. In any event, the fact that they were not put to Mr Reis means that the court is left with little further material by which it might judge the reliability of the evidence given by Mr Smith. Mr Reis was asked in re-examination about the electron microscope image at 678/660 and said that he did not see that the court could draw the inference of any gross manufacturing defect from that. However, such evidence suffers from the problem that it was being given very much "on the hoof" and may not reflect a considered opinion on the point.

Given my rejection of this explanation, I am left unpersuaded by the Defendant's case that the failure was due to manufacturing defect. On balance, it is more probable that Mr Reis' explanation of a weakness associated with the camel toe feature caused this failure than that it was caused by a manufacturing defect which, notwithstanding extensive investigation, remains unidentified.

Permission to Appeal

Subsequent to this judgment being sent out in draft, the Defendant sought permission to appeal. Having accepted the factual findings, those four grounds are:

(a) That I failed to bear in mind that, in a "two cause" case such as this, where the court rejects one of the causes, it must accept the other.

(b) That, having found that the design failure was an improbable cause, I should have accepted the other cause, namely manufacturing defect, to be the probable cause

(c) That I erred in finding that the Defendant was obliged to find an identified manufacturing cause; it was enough for the Defendant to succeed to show that a design cause was improbable.

(d) That it is logically unsustainable for me, having found a design cause to be improbable to have found a manufacturing cause to be even more improbable.

In my judgment, these are all aspects of the same argument, which is best summarised in the fourth proposition above. However I do not accept that this involves any logical fallacy. It is clear that I used the word "improbable" not in the sense of failing to satisfy the balance of probabilities, but in the more general sense of being unlikely. Even in "two cause cases", both suggested causes may be unlikely. In that context, it is the less unlikely of the two which satisfies the balance of probabilities. As I set out at paragraph 141 of this judgment, I found a design weakness to be the more probable cause.

For these reasons I refuse permission to appeal.