This judgment was handed down by the judge remotely by circulation to the parties’ representatives by email and release to The National Archives. The date and time for hand-down is deemed to be Thursday 27 October 2022 at 10:00am.

Mr Justice Foxton :

INTRODUCTION

1. This is the Claimant’s (Sweden’s) application for summary judgment on its claims against the First to Third, Sixth, Seventh, Tenth, Twelfth and Thirteenth Defendants (the SJ Respondents). Sweden claims that the SJ Respondents were parties to a substantial fraud which resulted in the misappropriation of in excess of €115m from the pension saving accounts of some 46,222 Swedish pension savers.

2. The SJ Respondents comprise:

i) The First to Third and Sixth Defendants, who are individuals. The Second and Third Defendants appeared in person at the hearing. The First Defendant chose not to appear. The Sixth Defendant has not engaged with the proceedings at any stage.

ii) The Seventh, Tenth, Twelfth and Thirteenth Defendants, who are companies. The Twelfth and Thirteenth Defendants have entered into liquidation. Their liquidator has been informed of the summary judgment application, and has not participated at the hearing. The other corporate Defendants have not engaged with the proceedings.

3. In the run-up to the hearing, Sweden reached settlements with:

i) the Fourth Defendant (Mr Deckmark) who was the managing director of Optimus Fonder AB (Optimus Fonder); and

ii) the Fifth Defendant (Mr Farrell), who was the Chief Executive Officer of Temple Asset Management (TAM).

The applicable principles

4. Lewison J’s summary of the principles which are to be applied when the court is asked summarily to determine a claim in EasyAir Ltd v Opal Telecom Ltd [2009] EWHC 339 (Ch), [15] is well-known and it is not necessary to set it out.

5. There are two features of the present application which merit further consideration.

i) First, the causes of action on which Sweden seeks summary judgment involve allegations of dishonesty. That clearly does not preclude a summary determination (Wrexham Association Football Club v Crucialmove Ltd [2007] BCC 139, [51]). However, I accept that an application of that kind is one which the court must approach with considerable caution (see Cockerill J’s judgments in Foglia v The Family Officer [2021] EWHC 650 (Comm), [14] and King v Stiefel [2021] EWHC 1045 (Comm), [21]-[22]).

ii) Second, summary judgment applications are often made at a stage when there has been limited exploration of the underlying evidence, a factor which requires the court considering such an application to have regard not only to the evidence before it, but also to such evidence as can “reasonably be expected to be available at trial” (Royal Brompton Hospital NHS Trust v Hammond (No 5) [2001] EWCA Civ 550, [19]). In this case, however, there have been lengthy criminal proceedings relating to the events which give rise to Sweden’s claim in these proceedings, in the course of which a large volume of contemporaneous documentation has been produced. 17,000 pages of documents have been obtained from the criminal trial concerned with the Optimus phase, and 44,000 pages of documents have been obtained from the criminal trial concerned with the Falcon phase.

iii) There was unchallenged evidence before me as to the broad powers of the Swedish prosecuting authorities in relation to the gathering of evidence, the extensive use of made those powers in relation to the criminal trials relating to the Optimus and Falcon phases, and the prosecutor’s legal duties to obtain and provide relevant evidence to those charged with criminal offences. The relevant material was set out in Advokatfirman Hammarskiöld & Co AB’s (Hammarskiöld’s) letter of 25 August 2022.

iv) As I noted in Serious Fraud Office v Hotel Portfolio II UK Limited [2021] EWHC 1273 (Comm), [8]:

“[A] summary judgment application may be brought at a relatively early stage in the life of an action or the wider dispute of which it forms part, before disclosure or evidence gathering is substantially underway, in which context the need for the court to have regard to ‘the evidence that can reasonably be expected to be available at trial’ will often be a compelling reason why it is not possible to conclude at the summary judgment stage that the claim or defence lacks a realistic prospect of success. On occasions, however, a summary judgment application is brought when the available processes for procuring evidence have already been deployed, with the prospect of anything further becoming available at trial being substantially diminished.”

The procedural history

6. These proceedings were commenced in early 2020, and at the outset I granted a Worldwide Freezing Order (the WFO) against each of the First Defendant (Mr Ingmanson), the Second Defendant (Mr Bishop) and the Third Defendant (Mr Gergeo) and against various companies.

7. In April 2020, the Swedish Court convicted Mr Ingmanson and Mr Bishop in relation to offences said to arise from their involvement with Optimus (see [21(i)] below). In October 202, those convictions were upheld on appeal. In March 2021, the Swedish Court convicted Mr Ingmanson and Mr Gergeo in relation to their involvement with the Falcon phase (see [21(ii)] below), as well as fining the Eleventh and Twelfth Defendants. It was common ground that those convictions have no evidential status before me, albeit the evidence available to the Swedish Court can be placed before me for my assessment (Rogers v Hoyle [2015] QB 265, [32]-[57]).

8. None of the SJ Respondents filed an acknowledgment of service or a defence. However, Sweden sought permission from the court to obtain summary judgment on the merits rather than entering judgment in default. Permission was granted by Calver J on 26 November 2021.

9. Sweden’s application, and the bulk of its evidence in support of the application, was served in July 2021. The evidence before the court comprises:

i) Witness statements from Ms Blom-Cooper exhibiting documents from the Swedish criminal proceedings.

ii) Expert evidence of Swedish law and Maltese law.

iii) A forensic accountancy report from Mr Stephen Holt of Grant Thornton (the Grant Thornton Report).

iv) A share valuation report from Ms Faye-Hall of Smith & Williamson.

10. The bundles for the hearing comprise thirteen double-sided bundles (excluding authorities).

11. Mr Bishop filed two skeleton arguments (both of which cross-referred to the pagination in the hearing bundles) and sent a letter to the court. He also made oral submissions at the hearing. Mr Gergeo also made oral submissions at the hearing, although he did not file any documents. None of the other SJ Respondents filed any documents.

CAN THE SUMMARY JUDGMENT APPLICATION FAIRLY BE DETERMINED?

12. Mr Ingmanson, Mr Bishop and Mr Gergeo are all serving sentences of imprisonment. Mr Bishop and Mr Gergeo participated in the hearing via a video link from prison. Their incarceration has undoubtedly curtailed their ability to review the material served for this application.

13. Mr Bishop argued that the summary judgment application against him cannot fairly be determined, and should be dismissed. He says that he has only had 12 hours to study Sweden’s documents since 4 November 2021, and is not permitted to retain notes in his cell. On Mr Bishop’s account, as at 19 August 2022, he had only been allowed to review the case materials on the following occasions:

i) 3 hours on 11 November 2021.

ii) 3 hours on 17 December 2021.

iii) 6 hours on 6 January 2022.

14. However, it would appear that Mr Bishop has had further access to the documents since the 6 January 2022 because his skeleton arguments filed for this hearing included hearing bundle references. While Mr Bishop stated in correspondence that he had been denied access to documents following requests made on 8 April, 16 May and 1 August 2022, the Swedish prison authorities stated that Mr Bishop had made a request for access to the documents on 8 April and that he was permitted access to the documents on 16 May. They also said that there was no record of any requests by Mr Bishop on 16 May and 1 August. Further, they stated that Mr Bishop had been offered the opportunity to inspect documents on 11 August 2022, but had not taken it up. An official from the Swedish prison service stated on 25 August 2022:

“I spoke to him on Tuesday regarding access to the documents, as there is more that he wants to see, he will apply to see his documents again and he will be invited to see them in due course”.

15. It is clear from the two skeleton arguments filed for this hearing that Mr Bishop has had access to the summary judgment materials which were before Mr Justice Calver in November 2021 for the purposes of Sweden’s application for permission to seek summary judgment, and to the bundles for this hearing (to which specific reference was made, using the page references in those bundles). However, it became apparent during the first day of this hearing that Mr Bishop only had access to the former set of bundles at that point, not the further hearing bundles served in September 2022. That was remedied during the second day of the hearing, in the course of which Mr Bishop read and elaborated on a written submission which had referred to the hearing bundles. The key documents in this application were in the first set of bundles produced in November 2021, and which were available to Mr Bishop.

16. Nonetheless, I accept that Mr Bishop’s ability to prepare for this application has been far from ideal, and that this is something which needs to be kept very much in mind when determining what weight can be placed on the evidence and on Mr Bishop’s failure to respond to the same. I am satisfied that this is also likely to be the case for Mr Ingmanson. However, Mr Bishop and Mr Ingmanson have been aware of the nature of the allegations made against them in relation to Optimus since 2020, as these featured at the criminal trial at which they were represented by lawyers and had a full opportunity to defend themselves. The documents from that trial were made available by the prosecution to the Defendants and their legal team. That is also the case for Mr Ingmanson (but not Mr Bishop) so far as the criminal trial relating to the Falcon phase is concerned.

17. The position of Mr Gergeo is the converse of that of Mr Bishop. Mr Gergeo was not charged by the Swedish prosecutor with any criminal offences arising from the Optimus phase, and he did not participate in that trial. However, he was charged with offences arising from the Falcon phase, and participated in the criminal trial concerned with the Falcon phase.

18. Mr Gergeo also argued that he had not had a fair opportunity to participate in the hearing, because he had not received all of the documents in Swedish, and had not had an opportunity to consult with his Swedish lawyer. The position with regard to Mr Gergeo is as follows:

i) Mr Gergeo was at liberty from 19 March 2020 to June 2022. Throughout that period, therefore, he was able to review the material served in support of the summary judgment application, the vast bulk of which was served on him in 2021, with Swedish translations by the end of year.

ii) On his evidence, he only had one day with the hearing bundles, on 12 October 2022.

iii) I am satisfied that Mr Gergeo has a reasonable grasp of English.

iv) He received Sweden’s skeleton argument in a Swedish translation on 12 October 2022, and was able at the hearing to make a number of submissions by reference to it.

19. I am satisfied that Mr Bishop, Mr Ingmanson and Mr Gergeo were able to answer the key themes of the case advanced against them. However, they were (or in Mr Ingmanson’s case would have been) at a disadvantage in dealing with issues of detail. I have kept this firmly in mind.

THE BACKGROUND

20. The Swedish pension system has various types of pension provision, including a compulsory premium pension (PPM), in which a percentage of a pension saver’s earnings is put into an account, which is invested in investment funds selected by the pension saver from an online platform that the Swedish Pension Authority (SPA) maintains. Each pension saver has a PPM account. Among the investments which might be made were investments in so-called UCITS funds where these had been approved by the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority (SFSA). UCITS funds are those meeting the requirements of the Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities Directive 209/65/EC.

21. A company that wished to participate in the PPM was required to

enter into a cooperation agreement with the SPA. This case arises from two UCITS funds which were listed on the PPM online platform:

i) the Optimus High Yield Fund (Optimus), managed by Optimus Fonder which entered into a co-operation agreement with the SPA on 26 March 2012; and

ii) the Falcon Funds SICA V plc (Falcon) which entered into a co-operation agreement with the SPA in relation to three funders under its management.

22. The events concerning these two separate funds have been described in the evidence as the Optimus phase and the Falcon phase. I shall adopt the same descriptions in this judgment.

THE OPTIMUS PHASE

The position on the facts

23. In this section, I set out those findings which I am satisfied Sweden will establish at trial, and which there is no realistic prospect of Sweden not establishing. The findings reflect the evidence which I have seen, and in particular the contemporaneous documents. In some cases, the facts are not substantially in dispute, and I have therefore not elaborated on the findings. Where the factual assertions are more controversial, I explain my reasons for concluding that the facts are clearly beyond the scope for realistic dispute.

24. On 17 June 2012, a company owned by Mr Bishop, ABSIG LLC (ABSIG), entered into a share transfer agreement to acquire Optimus Fonder, which transfer was approved by the SFSA on 16 November 2012. 50% of ABSIG was held by Mr Bishop personally, and the other 50% by ABS LLC, a company which Mr Bishop owned.

25. On 18 July 2012, ABSIG and Mr Bishop signed an exclusivity agreement with the Seventh Defendant (SVC (UK)). Under that exclusivity agreement, SVC (UK) was to solicit investors for various “financial products and mortgage backed securities” identified by ABSIG, in return for the payment of commission. SVC (UK) is sometimes referred to in the contemporary documents as “Solid”. SVC (UK) is a company which was owned 50-50 by Mr Ingmanson and Mr Gergeo until 7 October 2015, when Mr Ingmanson transferred his shares to Mr Gergeo. Mr Ingmanson and Mr Gergeo were both directors of SVC (UK), until 7 October 2015 in the case of Mr Ingmanson and 6 October 2017 in the case of Mr Gergeo.

26. Sweden alleges that between 2012 and 2013, the First to Third Defendants procured the purchase by Optimus using pension funds of mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) at inflated prices from companies owned by some or all of them.

27. It is clear that from 10 August 2012, Optimus purchased 9 MBSs directly from ABS Investment Group LLC (ABS), which is a corporate affiliate of ABSIG and is a company owned by Mr Bishop.

28. So far as these transactions were concerned:

i) As I have mentioned, on 18 July 2012, SVC (UK) entered into an exclusivity agreement with ABSIG under which it was entitled to commission payments for sale of ABSIG’s financial products. The exclusivity agreement was signed by Mr Bishop for ABSIG and Messrs Ingmanson and Gergeo for SVC (UK).

ii) On 15 August 2012, Optimus bought its first MBS from ABS, and SVC (UK) received a commission on the sale.

iii) ABS’s involvement in these sales was hidden, with the seller being identified as the broker Auriga. Mr Bishop informed Mr Ingmanson that Mr Deckman must “buy through Auriga or some other broker/dealer …. So this is the language that PSA and [Mr Deckman] want to see”.

iv) It is clear that Mr Bishop determined the price which Optimus paid for the MBSs. An email of 21 December 2012 from Mr Bishop to Mr Ingmanson referred to the price which ABS would pay to acquire a bond, the price it would charge Optimus, and the “arbitrage” which ABS planned to make on the trade.

29. From 14 February 2013, Optimus purchased 8 MBSs directly from SVC (UK), (rather than directly from ABS). However, SVC (UK) first purchased those MBSs from ABS, albeit on terms whereby SVC( UK) made no payment to ABS until it had been paid by Optimus.

i) Thus, on 15 February 2013, Mr Bishop emailed Mr Ingmanson details of a bond (the BOAMS bond) and referred to the co-ordinated transaction which would lead to Optimus acquiring the bond:

“Emil

Please find attached the trade tickets for the BOAMS bond, being sold:

(1) ABS to Solid Venture Capital; and

(2) Solid Venture Capital to Traction High Yield [i.e.. Optimus]”.

ii) On 14 April 2013, Mr Bishop emailed Mr Ingmanson about a bond he was targeting, on which ABS would spend $3.7m with “$740,000 arb[itrage] at SVC”.

iii) An email of 7 June 2013 sent by Mr Bishop referred to profits which would be made on the sale of bonds to Optimus, which would generate funds for the acquisition of an entity called Positiv Pension and lead to ABSIG and SVC (UK) each making $2m:

“With the sale of the 3 Fund V bonds that we are considering today, we should have approximately USD 6 million in cash. This will cover our purchase price for Positiv Pension on June 28 exactly.

We will sell 7 bonds out of the Fund IV portfolio to Optimus …This one transaction will produce abut USD5.5 million in profit. One more ‘turn’ during the second two seeks of July will finish paying the purchase price for Positive, and produce USD 2 million for ABSIG arb[itrage] and USD 2 million for Solid arb[itrage]”.

In the event, the “turn” or arbitrage on these bonds was $4,451,682.

iv) Similarly, on 5 August 2013, Mr Bishop emailed Mr Ingmanson about a bond which had to be repurchased (the FNLC bond) attaching two trade tickets. The first was for ABS to buy the bond from SVC (UK) for $639,403.34, and the second was for SVC (UK) to buy the bond back from Optimus for $710,504.18 (those repurchase prices reflecting the difference in the original acquisition cost).

30. On the evidence, it is clear beyond any realistic scope for argument that ABS sold the MBSs to Optimus, or SVC (UK) for on-sale to Optimus, at substantially more than it had paid to acquire them, as did SVC (UK) when it was the selling party. It is also indisputable that the prices paid by Optimus were determined by Mr Bishop and Mr Ingmanson as part of arrangement intended to allow them and companies associated with them to make large profits from these sales. Contemporaneous documents relating to these transactions included the following:

i) On 11 December 2012, Mr Ingmanson emailed Mr Bishop stating “Super! Super! We received 42 million today from the pension authority!!!! Double what we expected. You can prepare another MBS of the same size right away. We are going to break the half billion line before Christmas”. This clearly linked Mr Ingmanson and Mr Bishop with the sale of MBS transactions to Optimus.

ii) In an email of 11 December 2012, Mr Ingmanson asked Mr Bishop to “find another MBS of the same size and arbitrage ASAP. We have enough volume in the fund to buy it. Also everybody is now on board on the 1 billion goal by the end of Q1 …”. The reference to arbitrage is, in context, clearly a reference to making a turn by selling the MBS on for more than the acquisition cost. The document (and others like it) clearly establish Mr Ingmanson’s involvement in the process of sourcing and selling MBS transactions to Optimus.

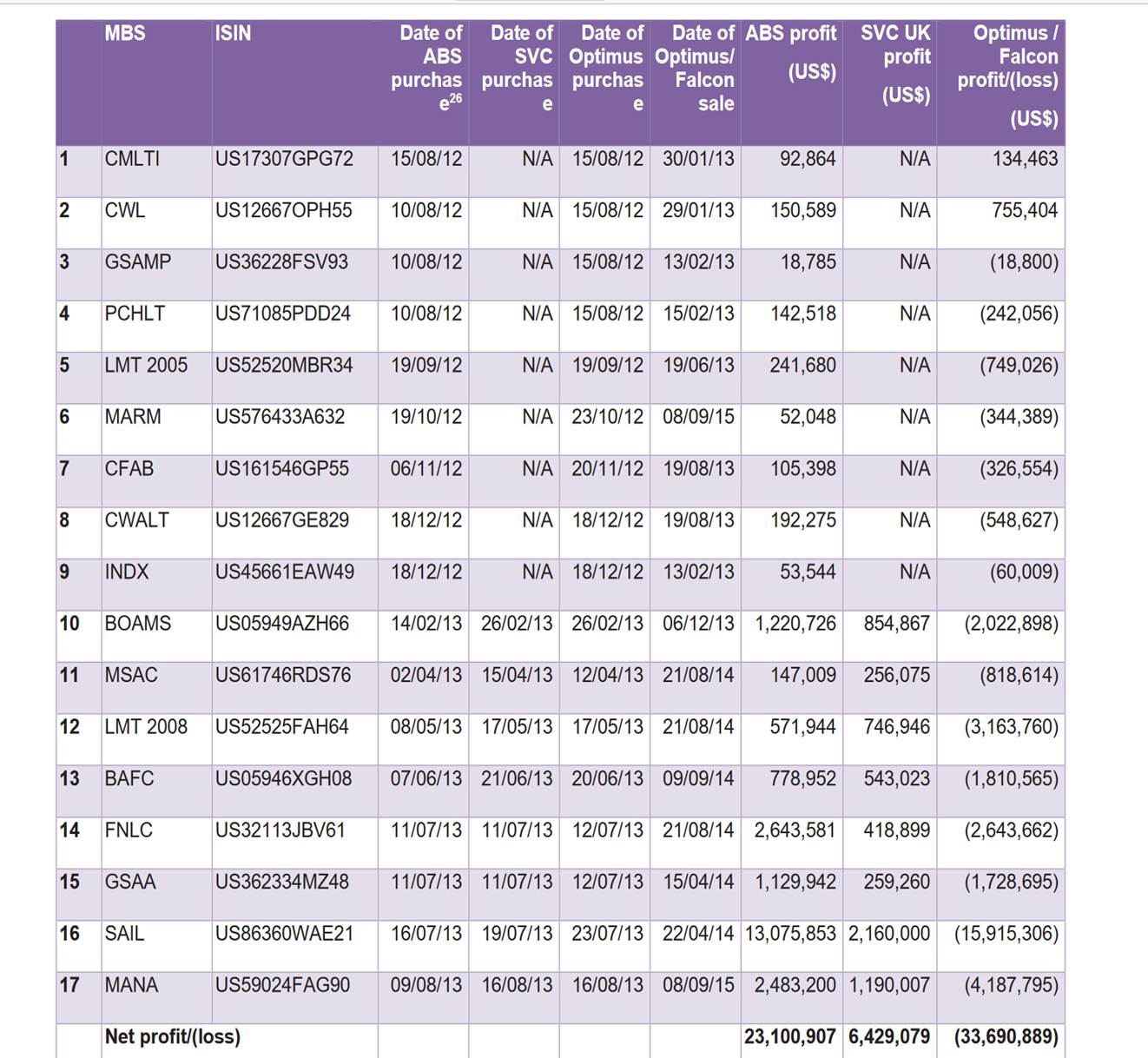

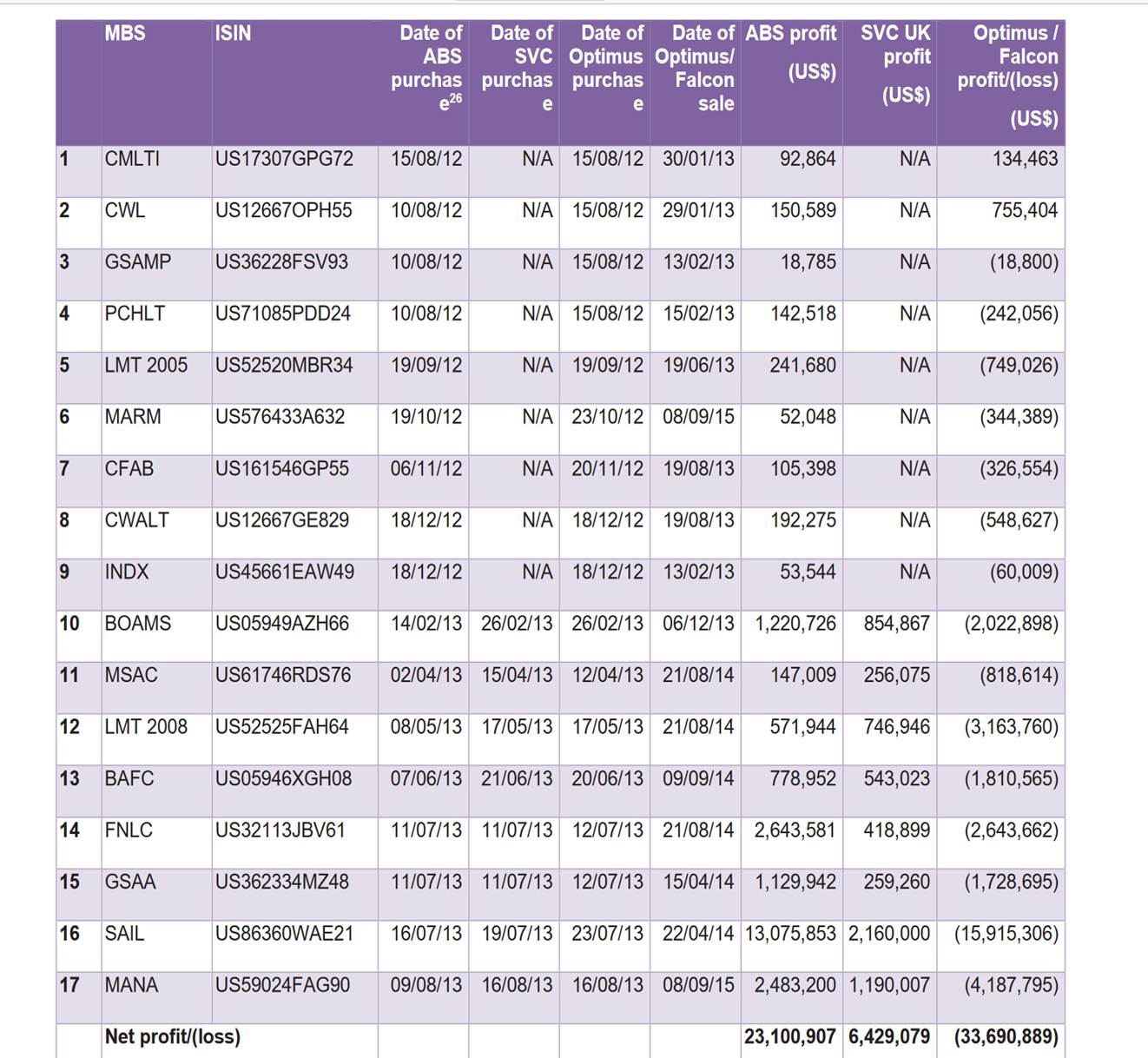

iii) The Grant Thornton Report compares the price paid by Optimus for the MBSs with available trade data at the relevant period. Where ABS sold the MBSs to Optimus, it made an average profit on 21% on each MBS with SVC (UK) also obtaining commission. Where ABS sold the MBSs to SVC (UK) who on-sold them to Optimus, ABS made an average profit of 114% and SVC (UK) of a further 15%. ABS’s total profit was $23.1m and SVC (UK) made commissions of $750,000 and profit of $6.4m.

iv) Further, a note in Mr Bishop’s handwriting refers to the mark-up being imposed on certain transactions, varying from 10% to 75%, and sets out information to be given to SVU (UK) and Mr Deckmark about the level of mark-up. Its terms suggest that different individuals were being given different accounts of the level of mark-up:

a) “Tell Solid and ABSIG that mark-up is @ 50% …”;

b) “Tell Ulf [Deckmark] that mark-up is only 10% of total … and that I will leave 10% of total … in the deal”;

c) “MAB [Mr Bishop] - Make sure mark-up is at least 75%”.

It is clear, however, that Mr Bishop was co-ordinating the prices at which the MBS transactions were to be on-sold, on a basis whereby ABS and SVC (UK) would profit at Optimus’ expense.

31. The analysis in the Grant Thornton Report shows the following information:

32. The profits made by ABS and SVC (UK) are striking, both in aggregate and on individual MBS transactions (e.g., SAIL in which over $15m of profit was made at Optimus’ expense over the period from 16 to 27 July 2013).

33. Mr Bishop’s close involvement in fixing the price at which Optimus would acquire these MBS products, and the profits which ABS and SVC (UK) would make, is clear from the documents I have referred to in the preceding paragraphs.

34. There are numerous documents involving Mr Ingmanson which refer to the need (and steps being taken) to increase the size of funds under Optimus’ management, in order to increase the absolute value of the 10% of the funds under management which could be used to acquire MBSs or similar products:

i) On 11 March 2013, Mr Bishop emailed Mr Ingmanson referring to the additional funds which Optimus would need to attract “in order for this new purchase to keep our ‘trash’ holdings below 10%”, and asking Mr Ingmanson if he could raise the fund level to SEK 730 million before 25 March 2013. Mr Ingmanson relied “yes, I think so but I can’t guarantee it”.

ii) On 14 April 2013, Mr Bishop emailed Mr Ingmanson again referring to a bond he wished to acquire and sell to Optimus generating $740,000 at SVC” but stating “Optimus fund size needs to get to SEK 800 million before I can fund it”.

35. Optimus Fonder was required to provide daily valuations of its investments to the SPA. These were originally provided by ABS itself, However, by a letter dated 15 November 2012, Optimus entered into what appeared to be an agreement with an American valuation agent, Hayden Consulting LLC (Hayden) to provide those valuations (as per Hayden’s letter of 15 November 2012). That letter bears what appears to be the signature of a Mr Thomas Epperson for Hayden and Mr Deckmark for Optimus. Mr Thomas Epperson claims to be the founder of Hayden.

36. However:

i) Mr Bishop’s e-mail box shows that he had created an email address in the name [email protected], and metadata shows that it was Mr Bishop who was the author of the emails sent from that address. A report prepared by Domain Tools dated 17 October 2017 shows that the domain name “Haydenintl.com” is owned by Mr Bishop. When Mr Epperson was questioned by the FBI about emails sent from that address with valuations of the MBSs acquired by Optimus, he denied having sent the emails.

ii) The precise nature of Mr Epperson’s interactions with Mr Bishop is not clear, nor what level of knowledge Mr Epperson had. The material which has been produced raises a number of questions about Mr Epperson’s role. For that reason, it is necessary to approach Mr Epperson’s untested evidence with caution in the context of a summary judgment application.

iii) However, the contemporaneous documents establish the following:

a) A screenshot of Mr Bishop’s email shows an inbox for Haydenintl.

b) On 12 February 2016, Mr Bishop emailed Mr Ungheanu of ABS referring to ABS being “responsible for providing ‘third party’ valuation for ETIs on Nordic Power, Boardwalk, Pro Mittelstand and Solid Venture …” (the inverted commas around ‘third party’ appear in the original document). He continued:

“The valuations should be from ‘HAYDEN’ on a HAYDEN form, from a HAYDEN email.

…

Examples of valuations for three of them from Argentarius are attached here … for you to use as a template. Hayden’s valuations should always ‘approximate’ the Argentarius-Group valuations. Please prepare draft examples for me by next Tuesday, and a process and responsible party for this valuation process, as over time, there will be more ETIs”.

c) On 18 February 2016, Mr Bishop sent the draft “Hayden” valuations to Mr Ingmanson to approve, stating if they were approved, Hayden would “pdf” the valuations and send them back.

d) On 23 February 2016, an email was sent from [email protected] explaining how to access the Hayden email account, and giving the password for that email account and another email account, [email protected]. The address given for Hayden in the footer to those emails was Mr Bishop’s address in San Diego and the telephone number his phone number.

e) On 24 February 2016, Mr Bishop sent an email to various individuals including a “John Epperson”. On the basis of Mr Thomas Epperson’s FBI interview, this is Mr Thomas Epperson: his full name is John Thomas Epperson, and the email address was for a “jtepperson”. This email stated “you now need to monitor ‘[email protected]’ email (webmail and also put in on your mobile devices)” saying “I am in contact with Barbaros” - the Sixth Defendant, Barbaros Őkten - “through hayden email as ‘Tom’ for now. Will need to hand off this assignment now ….”

f) On 24 February 2016, an email from “Tom” at Hayden was sent to Mr Őkten saying “I understand that we may be providing monthly valuations for you on various ETIs. We are in a position to begin providing valuations for you immediately”.

g) On 25 February 2016, Mr Bishop sent a test email to the [email protected] account, presumably to check that the monitoring arrangements he had sought to put in place were working.

iv) It is impossible to conceive of an honest reason why Mr Bishop would be producing emails in Hayden’s name addressing the valuation of the MBSs which Optimus and Falcon acquired, and none has been offered. The only possible inference, absent such an explanation, is that Mr Bishop was presenting Hayden as independent when it was not, for the purposes of offering a false level of assurance as to the reliability of the valuations provided. It does not matter for this purpose whether or not Mr Epperson was a willing participant in, or innocent dupe, of these arrangements.

v) When the Optimus and Falcon funds were merged, an issue arose as to the discrepancy between valuations provided by “Hayden” for two MBSs in the Optimus portfolio, and “indicative Bloomberg prices” which were much lower. A presentation made to the Falcon board on 18 March 2015 stated “Optimus … has historically used Hayden as their valuation source since Bloomberg pricing has been considered `stale’ and not trustworthy”.

vi) The steps taken to give the impression that the MBSs being acquired by Optimus were being valued independently, and at values which were higher than those provided by established and independent market data organisations like Bloomberg, unexplained as they are, provide strong support for the assertion that the First and Second Defendants were involved in dishonestly profiting at Optimus’ expense, and intent on keeping their activities concealed.

37. Sweden’s case that the First and Second Defendants were involved in a scheme which involved selling MBSs to Optimus Fonder at inflated prices, so that they could profit through companies they owned at Sweden’s expense, is also supported by the following:

i) Mr Deckmark was the managing director of Optimus Fonder. Mr Bishop signed a letter to Mr Deckman dated 20 August 2012 stating (clearly falsely) that ABS was an “arms-length” valuer, who would “not purchase from or sell to any broker/dealer that is doing business with [Optimus] and [ABS] will not purchase from or sell to [Optimus] direct”.

ii) In April 2013, Mr Bishop signed three letters to Mr Deckmark stating that Optimus Fonder had not purchased any MBSs from Mr Bishop or his companies ABS and ABSIG or any entity related to them. Those letters were prepared for the purpose of addressing queries from the SFSA about conflicts of interest, although it is not clear if they were ever sent.

iii) On the basis of the material I have referred at [28]-[32] above, those statements were demonstrably untrue. The fact that Mr Bishop found it necessary to lie about this issue strongly supports the assertion that the scheme for selling MBSs to Optimus was a dishonest one.

iv) Mr Decker established an Isle of Man company called Zeptunus Limited (Zeptunus) on 19 December 2012. That is clear from the beneficial owner questionnaire which Mr Decker signed. However, the incorporation fees were paid by SVC (UK).

v) On 19 April 2013, Zeptunus signed consultancy agreements with ABS and SVC (UK). However, the agreements do not explain the nature of the services to be provided. A memorandum on ABS-headed paper prepared by Mr Bishop suggested that Zeptunus was “a consultancy firm, with expertise in sourcing, managing, underwriting and valuing bonds”. That explanation, in respect of a company established by Mr Decker 4 months before, was obviously untrue.

vi) $568,546 was paid by ABS to Zeptunus over the period 31 July to 15 October 2013. This was Zeptunus’ only source of income. No legitimate explanation has been offered for these payments. An email from Mr Bishop to Mr Ingmanson of 18 July 2013 relating to one such payment stated:

“I’m getting ready to pay Ulf [Deckmark] at the end of the month. FYI, I’m using a factor of half of the real arbitrage for July (it’s enough).

Check it out. We will owe him SEK 3.758.428 total. I will contribute half (SEK 1.879.214 from Solid and SEK 1.879.214 from ABS.”

Mr Ingmanson replied “as long as we get the 10% arb on this one …”.

vii) It is clear from this and other documents that the amounts paid to Zeptunus were linked to the amount of profit ABS and SVC (UK) made on bond sales to Optimus, albeit it would appear that Mr Bishop did not always give Mr Deckman an accurate statement of what those profits were. It is also clear that both Mr Ingmanson and Mr Bishop were aware of this.

viii) Mr Bishop’s computer had a sub-folder for Mr Deckmark which included invoices and details for payments to Zeptunus.

ix) Once again, it is difficult to see what honest explanation there could be for ABS and SVC (UK), two companies engaged in sourcing and selling MBSs to Optimus, paying amounts to an offshore company controlled by the managing director of Optimus, which amounts were linked to the profit (arbitrage) made on the MBS sales. None has been forthcoming.

x) Once again, that provides very strong support for Sweden’s case that the First and Second Defendants were involved in dishonestly profiting at Optimus’ expense, and had paid money to Mr Deckmark, who held a key executive role at Optimus, to keep him “on side” and in support of their plans.

Applicable law

38. There was no challenge to Sweden’s assertion that the law applicable to its claims so far as they concerned the Optimus phase was Swedish law. Whether that issue is approached by reference to Article 4(1) or 4(3) of Regulation (EC) 864/2007 (Rome II), I am satisfied that Swedish law is the applicable law.

Swedish law

39. The undisputed evidence of Swedish law, supported by the clear terms of the statute in question, is that a claim for damages arises under the Tort Liability Act (TLA). Pursuant to Chapter 2, §2 of the TLA, a person who causes:

i) pure economic loss;

ii) through a criminal offence;

is liable to compensate the victim of the loss.

40. It is also clear from the Swedish law evidence, and the terms of the Swedish Penal Code, that the following criminal offences exist under Swedish law.

41. First, the offences of fraud and gross fraud under Chapter 9 §1 and §3 of the Swedish Penal Code, which is committed when a person, by deception, induces someone into an action or omission that involves gain for the perpetrator or loss for the person deceived. The offence of gross fraud is committed when the fraud is of a particularly dangerous nature or involves a considerable value.

42. Second, the offences of breach of trust and gross breach of trust under Chapter 9 §5. This applies to a person who, on account of a position of trust, is given the task of managing a financial matter on behalf of someone else, and who abuses their position of trust and thereby causes a loss for their principal. Where the principal suffers a considerable or exceptionally painful loss, the offence of gross breach of trust is committed.

43. Third, Chapter 23 §4 provides that the offences created by the Swedish Penal Code are committed not only by the principal offender, but “anyone who promoted it by advice or deed”.

Res judicata?

44. Mr Bishop suggested that Sweden’s claims relating to the Optimus phase were barred by the doctrine of res judicata, merger, cause of action estoppel or the allied doctrine in Henderson v Henderson. Mr Bishop relied in this regard on the fact that the same facts had formed the basis of the criminal prosecutions against him. However:

i) It is well-settled that a criminal convictions and acquittals do not give rise to a plea of res judicata: see Spencer Bower & Handley: Res Judicata (5th), [11-01] and [11-09].

ii) Nor do criminal proceedings involve the assertion of a cause of action (so there can be no question of cause of action estoppel or a cause of action merging in a criminal conviction).

iii) In any event. Mr Bishop was convicted at the criminal trial. Had there been any issue estoppel or res judicata, it would have operated against him and not against Sweden.

iv) On the expert evidence before me, the TLA claims do not require a criminal conviction. I have seen nothing which suggest it would have been appropriate to bring the civil claims in the criminal trial and it is not arguable that the decision to bring those claims in civil proceedings in England contravenes the rule in Henderson v Henderson.

Did any of Mr Bishop, Mr Ingmanson and/or Mr Gergeo commit offences contrary to the Swedish Penal Code

Mr Bishop

45. Mr Bishop’s written and oral submissions scarcely engaged with the events of the Optimus phase. Instead, they concentrated on the Falcon phase, or on procedural or technical answers to the claims. Mr Bishop’s failure to offer any explanation of the rather striking events relating to Optimus’ acquisition of MBSs is telling. I am satisfied that the reason that no explanation was given was that none could be given.

46. I am satisfied that there is no arguable defence to Sweden’s claim that M Bishop committed an offence of breach of trust, and indeed gross breach of trust, and that he also promoted breach of trust and gross breach of trust by Mr Deckmark.

47. Mr Bishop was a board member of Optimus Fonder, and in that capacity held a position of trust in relation to the management of the Optimus Fund which was owned by Sweden. Mr Bishop clearly abused that position of trust by participating in the scheme I have set out above to commit it to buy MBS products from entities owned or controlled by himself of Mr Ingmanson at inflated prices, thereby causing loss to Sweden (in the form of the over-payment).

48. It is equally clear and undeniable that Mr Deckmark was also guilty of the offence of breach of trust, and indeed gross breach of trust. As the managing director of Optimus Fonder, he too held a position of trust in relation to the management of Sweden’s assets. He abused that trust by participating in the MBS scheme to make a profit by over-charging Optimus for those assets, obtaining a share of the profit made.

49. I would note that my conclusion, on the undisputable facts, that Mr Bishop and Mr Deckmark held positions of trust for the purposes of the Swedish Penal Code was also the conclusion reached by the Stockholm City Court in its Judgment of 17 April 2020, which conclusion was affirmed by the Svea Court of Appeals in its decision on 22 October 2020.

50. It is clear beyond any realistic scope for argument that Mr Bishop is guilty of the offence of promoting Mr Deckmark’s breach of trust, by agreeing to pay Mr Deckmark some part of the over-charge and organising that payment.

Mr Ingmanson

51. It is clear beyond any realistic scope for argument that Mr Ingmanson was guilty of the offence of promoting the breaches of trust by Mr Bishop and Mr Ingmanson to which I have referred. He was clearly the prime mover in the scheme to strip funds from Optimus by over-charging it for the MBS transactions he asked Mr Bishop to source.

Mr Gergeo

52. The position with regard to Mr Gergeo is more complex. The only criminal offence which Sweden alleges in these proceedings that Mr Gergeo committed is the offence of fraud. However, that requires Mr Gergeo to have deceived Sweden and thereby induced Sweden to act in a way which causes loss to Sweden or gain to Mr Gergeo. The pleaded case is that:

“From at least 5 August 2012 until at least August 2013, Messrs Ingmanson, Bishop, Gergeo and Deckmark by deception intentionally induced the Claimant into retaining investments in Optimus and/or investing in Optimus and/or making further investments into Optimus on the basis that Optimus was a legitimate and/or properly and conscientiously managed UCITS fund, when in fact by virtue of Mr Bishop’s direction and/or control of Optimus Fonder, and by virtue of Mr Deckmark’s bribery and dereliction of his duties, the Claimant’s monies in Optimus was used (and were planned to be used) to buy MBS products at a substantially marked up and/or inflated prices ….”

53. However, as Sweden accepted, it has not pleaded any statements or behaviour by Mr Gergeo, or to which he was a party, which had induced Sweden to act in a particular way, nor was its evidence presented in this way. The thrust of Sweden’s case at the hearing was that Mr Gergeo had promoted the breaches of trust by Mr Bishop and Mr Deckmark. However, Mr Eschwege accepted that no such case had been pleaded against Mr Gergeo.

54. As a litigant in person, I would have been reluctant to allow Sweden to introduce such a case at the hearing (and no attempt was made to do so). In any event, there are further reasons why I would have been unwilling to permit Sweden to change its case in the context of this application:

i) Mr Gergeo was not charged by the Swedish prosecutor with criminal offences relating to the Optimus phase, nor been a defendant in the trial concerned with the Optimus phase. He would not, therefore, have had the opportunity which Mr Bishop and Mr Ingmanson both had to consider the evidence relating to that phase with Swedish lawyers, nor to familiarise himself with that documentation.

ii) I was not shown anything like the volume of documentation featuring Mr Gergeo in relation to the complaints made about the Optimus phase. In particular, I was not shown material linking Mr Gergeo to the Hayden valuations, the arbitrage made on MBSs or the payments to Mr Deckmark.

iii) It is right to note that SVC (UK), a company in which Mr Gergeo held a 50% share, was heavily involved in the Optimus phase and that Mr Gergeo was one of the two signatories on its behalf to the exclusivity agreement with ABSIG. Mr Gergeo also held 50% of Strategi Placering which was involved in the growth of the PPM funds under Optimus management. However, it was Mr Gergeo’s submission that his involvement was largely focussed on the music business pursued by SVC (UK)’s subsidiary and that he had no access to SVC (UK)’s bank accounts. He suggested that his signature had been forged on at least some SVC (UK) documents.

iv) While Mr Casey KC referred to various reasons why this was said not to constitute a satisfactory explanation, the possibility that Mr Gergeo would have had more to say on this issue had it been alleged that he had promoted breaches of trust by Mr Bishop and Mr Deckmark in the Optimus phase is another reason why I would not have thought it appropriate to reach a summary determination of that issue so far as he was concerned.

Did the criminal offenses committed by Mr Bishop and Mr Ingmanson caused Sweden loss?

55. It is clear that causing Sweden to overpay for the MBS transactions directly caused Sweden pure economic loss, in the form of the reduction of the funds which belonged to Sweden. However, one point taken by Mr Bishop is that any direct loss was suffered by the SPA and not Sweden.

56. The issue of whether Sweden or the SPA had title to the funds claimed and had suffered the loss alleged is one of Swedish law. I was referred to the expert evidence of Per Sundin and Mattias Anjou of Hammarskiöld on this issue. The effect of that evidence is as follows:

i) The SPA is a government agency directly organised under the Swedish government, but not a separate legal person, and the Swedish government is an entity subsumed within the Swedish state.

ii) The only legal entity, therefore, is Sweden, of which the SPA is an integrated part. When the SPA brings legal action, it does so in the name of the Kingdom of Sweden.

iii) It is the Kingdom of Sweden which is the shareholder in the funds to which the pension savers’ premia are allocated.

57. That opinion is supported by the decision of the Svea Court of Appeal in the Optimus case, which ordered Mr Ingmanson, Mr Bishop and Mr Deckmark to make payments to the Swedish state, not the SPA. It is also supported by the terms of the co-operation agreements entered into with both Optimus and Falcon, which describe the agreement as one between “the Swedish Government through The Swedish Pension Agency” and the relevant fund.

58. Given Sweden’s ownership of the funds in Optimus, which is clearly established by the Swedish law expert evidence before me, I am satisfied that there is nothing in Mr Bishop’s submission that the overpayments did not constitute direct loss and damage to Sweden under Swedish law.

Loss

59. On the unchallenged expert evidence in the Grant Thornton Report, the MBS transactions caused Optimus (and hence Sweden) a net loss of $33,690,889, comprising losses of $34,580,756, and a profit on two MBS transactions ($134,463 on CMLTI and $755,404 on CWL). However, the profit made by ABS and SVC (UK) on those transactions (and hence the amount of the over-payment) was the lower figure of US$29,529,986.

60. I can see scope for argument as to which of these is the correct figure. However, I am satisfied that Mr Bishop and Mr Ingmanson have no realistic defence to the lowest of those figures of $29,529,986, and that Mr Bishop and Mr Ingmanson are each liable to Sweden in that amount, on a joint and several basis.

THE FALCON PHASE

The background

61. From 26 July 2013, reports appeared in the Swedish press which accused Strategi Placeirng, a company linked to Mr Ingmanson, of fraud, in connection with the transfer of pension funds to Optimus.

62. By September 2013, Mr Ingmanson was involved in plans to establish a new UCITS investment vehicle in Malta, Falcon, which was to be registered on the PPM platform.

63. On 18 September 2013, Mr Ingmanson sent an email about the Falcon fund into which Mr Gergeo was copied stating “here are the funds which we set up in Malta and which we will include in PPM, ASAP”.

64. In an email of 27 September 2013, Mr Ingmanson informed Mr Bishop:

“Optimus High Yield re domesticities from Sweden to Malta, and from Optimus to Bank of Valletta and Calamatta … Calamatta will manage the fund which will be in a SICAV …

We have appointed the board of directors in the SICAV and we will have the option to buy all the shares at any time. The SICAV can at any point change the manager (Calamatta) … which means that we are in control, but it won’t show to anyone which is good right now, given the situation we’re in

…

As soon as our three new UCITs IV funds are up and ready in the PPPM, which must be before February 24th 2014, we sell all assets in OHY [Optimus High Yield] and transfer the funds to the three new funds”.

65. The plan for the outset was for Falcon to target Swedish pension funds, as noted in an email from Mr Camilleri to Mr Ingmanson of 9 October 2013.

66. Falcon was incorporated and authorised by the Maltese Financial Services Authority (MFSA) as a UCITS fund on 22 November 2013. It established three funds:

i) The Falcon Aggressive Fund.

ii) The Falcon Balanced Fund.

iii) The Falcon Cautious Fund.

67. Falcon appointed Calamatta Cuschieri Investment Management Limited (Calamatta) as investment manager, Bank of Valletta (BOV) as custodian and Valletta Fund Services (VFS) as fund administrator. The Custody Agreement between Falcon and BOV and the Administration Agreement between Falcon, VFS and Calamatta were both dated 27 December 2013. Falcon issues its prospectus on the same date.

68. It is necessary to say something about the nature of the investment in Falcon:

i) In exchange for their investment, Falcon offered investors shares in the entity operating the relevant sub-fund.

ii) Those shares could be redeemed for the relevant Net Asset Value per share, which would reflect “all accrued income and expenses” (including, presumably, operating expenses).

iii) However, Falcon reserved the right to suspend the right of any shareholder to redeem their shares in exceptional circumstances.

iv) If Falcon had potential liabilities or other financial obligations the existence of which could only be confirmed after a Redemption Notice has been received and processed, or the sub-fund had current liabilities arising from past events which could not be fully determined, Falcon could withhold 2% of the amount for contingent liabilities.

v) Falcon reserved the right to reject any redemption request if it was believed to involve excessive and/or short-term trading or similarly abusive practices. The prospectus notes that “the Directors reserve the right to reject any conversion order for any reason without prior notice”.

vi) Various categories of fees are payable. In addition, Falcon was able to use the proceeds of redeemed investment for expenses. It is currently using the proceeds of investment to fund the legal proceedings it has commenced against Mr Ingmanson in Malta, and made it clear that it will be the surplus after meeting the expenses of litigation which will be returned to Sweden.

69. On 10 January 2014, Calamatta applied to enrol the three Falcon funds with the Swedish PPM. On 25 March 2014, “the Swedish Government, through the Swedish Pensions Agency” entered into a Co-operation Agreement with Falcon. The terms of the Co-operation Agreement included the following:

i) Falcon agreed to perform its obligations with care and in a professional manner.

ii) Falcon was liable to Sweden for the defaults of any service providers it engaged.

iii) The agreement was governed by Swedish law.

70. On 17 July 2014, Falcon’s funds were registered on the PPM platform.

71. With effect from August 2014, the SPA invested some €365m in the Falcon funds.

72. On 21 November 2014, Optimus Fonder applied to the SFSA to merge its funds with the Falcon Balanced Fund. On 26 January 2015, the SFSA gave its consent to the cross-border merger.

Applicable law

73. Sweden’s summary judgment claim in relation to the Falcon phase requires the court to be satisfied to the summary judgment standard that its claims in delict and for breach of fiduciary duty relating to the Falcon phase are governed by Maltese law and not Swedish law. For this purpose, it is necessary to consider the claims in delict and for breach of fiduciary duty separately.

74. So far as the claims in delict are concerned, the applicable law is determined by Article 4 of Rome II. This provides:

“1. Unless otherwise provided for in this Regulation, the law applicable to a non-contractual obligation arising out of a tort/delict shall be the law of the country in which the damage occurs irrespective of the country in which the event giving rise to the damage occurred and irrespective of the country or countries in which the indirect consequences of that event occur.

2. However, where the person claimed to be liable and the person sustaining damage both have their habitual residence in the same country at the time when the damage occurs, the law of that country shall apply.

3. Where it is clear from all the circumstances of the case that the tort/delict is manifestly more closely connected with a country other than that indicated in paragraphs 1 or 2, the law of that other country shall apply. A manifestly closer connection with another country might be based in particular on a pre-existing relationship between the parties, such as a contract, that is closely connected with the tort/delict in question.”

75. Mr Eschwege (who shared the submissions with Mr Casey KC and dealt with the topic of applicable law) argued that Article 4(1) applied here, and that the damage was suffered in Malta when funds held in Falcon were applied to the various classes of loss-making investments. He argues that it was only at that point that the loss to Sweden became irreversible, and it is only when there is an irreversible asset transfer from the claimant as a result of the defendant’s wrongful act that loss is suffered for Article 4(1) purposes. Mr Eschwege relied in this regard on the decisions of Mr Justice Marcus Smith in MX1 Ltd v Farahzad [2018] 1 WLR 5553 and Mr Justice Andrew Smith in Hillside (New Media) Ltd v Baasland [2010] 2 CLC 986. In MX1, entering into an agreement under which £100,000 was payable in England was held to amount to an irreversible loss. In Hillside, Andrew Smith J held that money transferred by a gambler to, in effect, a credit account with a gambling facility was not lost unless and until applied from the account in losing transactions.

76. Hillside was a case in which Mr Baasland had transferred funds to Hillside, which were replaced by a chose in action with Hillside which Mr Baasland could seek repayment of at will. If , as seems likely, those transfers to Hillside were made from a bank account, then what happened was that a chose in action which Mr Baasland had in a particular amount with one or more banks was replaced by a chose in action which Mr Baasland had in the same amount with the gaming company’s bank. One can well see why there is no loss in this case by the fact of that transfer alone (any more than there is a loss when cash is paid into a bank account in the claimant’s control).

77. In this case, however, the transfer of Sweden’s funds to Falcon was by way of a transaction under which it acquired shares in the Falcon funds and their attendant rights in return for the payments made. The loss which Sweden will suffer arises from the fact that those shares are worth less than the amount paid for them. I am satisfied that the better view is that acquiring those shares did involve a loss to Sweden. I note that in Raiffeisen Zentral Bank Osterreich AG v Tranos [2001] ILPr 9, [15], Longmore J observed:

“The loss cannot be said to have been suffered until the reliance had itself resulted in a concrete transaction that gives rise to a loss. In that sense, the initial damage was suffered when the credit facility was agreed”.

78. In this case, I am not persuaded to the summary judgment standard that irreversible loss was not suffered until the funds were applied by Falcon in losing investments. The application of the test of reversibility, when dependent on setting aside a sale contract, appears to me to raise very different issues to those which arise when liquidating the chose in action represented by a positive bank balance, and in any event, given the matters in [68] above, I am far from satisfied that reversing the share acquisition was quite as straightforward as Mr Eschwege’s submissions assumed. Applying the statement in Dicey, Morris & Collins on The Conflict of Laws (16th) [35-027] to which Mr Eschwege referred me - “in misappropriation cases … it seems appropriate to locate damage at the place where an asset … is taken from the control of the claimant or another person with whom the claimant has a relationship” - it is strongly arguable that this happened when Sweden’s funds became subject to the control of Falcon and the powers of its directors or those operating behind the scenes.

79. Further, so far as Mr Gergeo, Mr Őkten and the Twelfth and Thirteenth Defendants are concerned, Sweden’s case would appear (at least arguably) to fall within Article 4(2), with both Sweden and the relevant Defendant having their habitual residence in Sweden at the relevant time:

i) So far as Mr Gergeo is concerned, corporate filings identify his address as being in Sweden in 2015, and his affidavit says that he lived in Sweden until January 2017 (which is after Sweden contends it suffered loss).

ii) As regards the Twelfth and Thirteenth Defendants, they are incorporated in Sweden, and it is at least arguable that their central management and control is exercised where Mr Gergeo is habitually resident, which is arguably Sweden.

iii) So far as Mr Őkten is concerned, he had an address in Sweden, but he also worked for TAM in Malta. I accept that Mr Őkten might well have been habitually resident in Malta when the losses are alleged to have been suffered, but the position is unclear.

80. That leaves the further issue that, even if Sweden had been right about the place of loss for the purposes of Article 4(1) of Rome II, this was a case in which that general rule was displaced by the “exception” in Article 4(3). There are convenient summaries of the approach to be taken in determining whether Article 4(3) is engaged from Mr Justice Bryan in Lakatamia v Su [2021] EWHC 1907 (Comm), [859] and Mr Justice Picken in Avonwick Holdings Limited v Azitio Holdings Limited [2020] EWHC 1844 (Comm), [156] and [175]. From the summaries in those authorities, I have had particular regard to the following:

i) The fact that Article 4(3) is an exception to the general rule in Article 4(1) does not mean that it should be given an overly restrictive construction.

ii) Before Article 4(3) applies, it is not required that the tort not be connected with the jurisdiction which would engage Article 4(1).

iii) “ All the circumstances" as referred to in Article 4(3) might include a variety of features, including the location of assets which are “at the heart of” the alleged wrongdoing, even if this is not the place where the direct damage occurred and any "pre-existing relationship between the parties, such as a contract, that is closely connected with the tort/delict in question".

iv) Article 4(3) has as its focus "agreements in place before the allegedly tortious acts took place" and not "mechanisms by which the allegedly dishonest scheme was implemented".

81. The essence of Sweden’s case is that the SJ Respondents were parties to an ongoing and continuing course of conduct intended to misappropriate Swedish pension funds. It is alleged that the establishment of Falcon was, in essence, a mechanism for implementing a dishonest scheme, when things became too hot in Sweden (and, in the context of its argument as to the effect of Maltese law, Sweden places particular emphasis on what is said to be mechanistic role of Falcon). Falcon was established to target Swedish pension funds, and was party to a Swedish law agreement in respect of those funds with Sweden.

82. Further, on Sweden’s case the same continuing course of conduct aimed at perpetrating misappropriation of the same assets gives rise to claims under two different systems of law. I accept that Article 4 is Rome II is not overtly hostile to the idea that where the same wrongful act causes damage in two different countries, two different systems of law may well be engaged. In MXI Ltd v. Farahzad , [44], Marcus Smith J stated:

“In my judgment, the applicable law pursuant to article 4(1) is not the place where the damage predominantly occurs. That is not what the article says. Article 4(1) refers to ‘the law of the country in which the damage occurs’ The natural reading is that where damage occurs across several jurisdictions, there will be several applicable laws. This is, of course, also consistent with the Explanatory Memorandum.”

83. Mr Eschwege also referred me to Dicey, Morris & Collins, [35-028]:

“A claimant may suffer direct financial loss in more than one country. In the Explanatory Memorandum, accompanying the Commission’s original proposal it is suggested that in such cases ‘the laws of all countries concerned will have to be applied on a distributive basis, applying what is known as Mosaikbetrachtung in German law’. This approach has been endorsed by the Court of Appeal, in relation to Arts 4 and 6 of the Rome II Regulation, in a case involving the alleged misuse of confidential information to manufacture and then sell articles in different markets worldwide. This may be one point where principle may ultimately yield to pragmatism, particularly in cases (such as a claim for non-monetary remedies) where the fragmented application of the laws of several countries may be impossible or exceedingly difficult. In such cases, the temptation may be to avoid this theoretical difficulty by seeking to locate the ‘direct damage in a single country or by making use of the ‘escape clause’ in Art.4(3) of the Regulation.”

84. In this regard, it may be appropriate (at least as a matter of emphasis) to distinguish between torts which have horizontal multi-jurisdictional effects, and those which have vertical multi-jurisdictional effects. The publication of a libellous tweet which is read and causes loss in a number of jurisdictions, or the use of confidential information to sell infringing products in a variety of countries, may present a rather stronger case for a “Mosaikbetrachtung” of applicable laws than a case such as the present, in which the defendants began causing loss to the claimant in one country, but adjusted their modus operandi so as to continue causing loss of essentially the same kind to the same claimant in another country.

85. The combined effect of the matters in [78] to [84] above is that I am satisfied that it is realistically arguable that Swedish law governs the tort claims arising from the Falcon phase as well (and indeed I regard that contention as having the better of the argument).

Breach of fiduciary duty claims

86. So far as the breach of fiduciary duty claims are concerned, as Mr Eschwege rightly submitted, this is a complex topic. He points me to the following summary in Dicey, Morris & Collins [36-069]-[36-070]:

i) If equitable obligations of a fiduciary character arise in the context of a contractual relationship, there is a strong argument that the law applicable to the parties’ contractual relationship under Rome I determines whether a fiduciary relationship exists and the nature and content of the duties imposed.

ii) I f, however, the equitable obligations are characterised as incidents of a company law relationship rather than as “contractual”, common law principles determine the applicable l aw ( company law matters are excluded from Rome I and Rome II).

iii) If a fiduciary duty arises where the parties were not in a prior relationship, such as in the case of a recipient of trust property, then the “better view” is that the obligation is non- contractual in nature and falls within the ambit of Rome II.

87. Many of the individuals against whom claims relating to the Falcon phase are brought had already had at least some involvement in the Optimus phase. That is certainly true of the First and Second Defendants, with Mr Bishop already being a fiduciary in respect of assets transferred from Optimus to Falcon, and Mr Ingmanson being closely involved in the investments made by Optimus. SVC (UK), in which Mr Gergeo had a 50% interest and of which he was a director, was also closely involved in the Optimus phase, albeit there is a dispute as to what involvement Mr Gergeo had personally. Further, the corporate Defendants against whom claims are brought in relation to the Falcon phase are alleged to have been controlled by one of those three individuals. All of those companies are alleged to be parties to a joint enterprise with the individual Defendants from the outset of the Falcon phase, rather than simply parties to particular investment decisions made at a later point in time.

88. So far as Falcon itself is concerned, it owed contractual obligations to Sweden which were governed by Swedish law (in the form of the Co-operation Agreement). To my mind, that agreement - by which Falcon becomes eligible to received PPM funds - is far more closely connected to Sweden’s claims than the subscription agreement. It is the Co-operation Agreement which Sweden terminated when the “balloon went up”, and the Co-operation Agreement to which Sweden’s Maltese law experts attach significance when explaining why fiduciary duties are owed by Falcon. Further, as explained below, Sweden is keen to pitch its claims relating to the Falcon phase not as those of a shareholder, but as those of an investor in respect of its own funds. Sweden submitted that its claims against the SJ Respondents were effectively as accessories to breaches of Falcon’s fiduciary duties. That all lends support for the view that Swedish law applies.

89. Further, Mr Eschwege submitted that the most persuasive analysis was one which treated the equitable claims as engaging Article 4 of Rome II. I have already given the reasons for concluding that the better view is that Article 4 leads to the application of Swedish law.

90. I am satisfied, therefore, that it is at least arguable that the claims for breach of fiduciary duty are also governed by Swedish law, and, on the facts of this case, I would not regard the contention that the tort and fiduciary claims were subject to different applicable laws as particularly satisfactory. In both cases, the gravamen of Sweden’s complaint is that duties owed to it in respect of funds emanating from it were breached, leading to the loss of those funds. The case is not about duties owed to Falcon, but about duties arising from the management of Sweden’s funds, which the SJ Respondents are accused of having targeted through Falcon.

The reflective loss rule under Maltese law

91. My conclusion on the applicable law issue is sufficient to defeat Sweden’s summary judgment case so far as it concerns the Falcon phase. However, I would in any event have found that there was a triable issue as to whether the no reflective loss rule precluded a claim by Sweden under Maltese law. That issue arises from the fact that Sweden acquired shares in the Falcon fund, the value of which has been diminished by the misappropriation or mis-investment of assets from those funds, but Falcon itself appears to have and is currently asserting claims against some of the alleged wrongdoers in relation to those same misappropriations.

92. Sweden’s evidence of Maltese law on this issue was provided by Dr David Zamit and Dr Kurt Xerri. The relevant section of their report provides as follows:

i) In Meatland Company Limited v Saviour Micallef 12 December 2001, the First Hall of the Civil Court applied the English decision in Prudential Assurance v Newman and held that only the company could sue when the shareholder’s loss consisted of a reduction in the value of its shares.

ii) In Martin Bonello v Cole 5th October 2001, the Court of Appeal referred with approval to the Newman principle, but held it did not apply to claims brought by one shareholder against another in respect of a lease taken out by the shareholders rather than the company, and where the claim involved a loss independent of that of the company.

iii) The Maltese court permit claims by shareholders acting in a derivative capacity on behalf of the company in circumstances of “fraud of minority, infringement of personal rights or the interests of justice”. The report observes that “the principles embraced by the Maltese court are those emanating from the eminent English judgment of Foss v Harbottle”. While Mr Casey KC referred to the words “interests of justice” as involving a general basis for disapplying the reflective loss principle in Maltese law, that is not how I interpret the report. Nor have I seen anything which would enable me to conclude, to a summary judgment standard, that a principle said to be relevant to individuals acting “to safeguard the company’s assets and rights through derivative actions” could apply in this case, when Falcon (under the control of KPMG) is not only able to safeguard its own rights and assets, but is presently doing so through proceedings it has commenced in the Malta courts.

iv) On the basis that Falcon was “purposely set up, and eventually used, as a vehicle for fraud” and that “the very establishment of Falcon was part of the fraudulent scheme from the beginning and therefore the reality is that the company was a simulated trading company”, the authors of the report contend that it followed that “every contract by which money was transferred from [Sweden] to Falcon was vitiated by this fraud” and “every contract by which money was invested in Falcon must be declared null and void”.

v) In those circumstances, they express the view that “Maltese law would not let the principle of the separate judicial personality of a company, upon which the rule of reflective loss is based, prevent them from analysing the reality of the situation and imposing liability on all persons responsible in circumstances in which the incorporation of the company itself constitutes part of a fraudulent artifice”. The only source cited in support of this proposition is a case dealing with the issue of piercing the corporate veil for the purpose of imposing liability on the person behind the company. It is, in short, a “proper defendant” case rather than “a proper claimant” case.

93. Stepping back, the following points are apparent:

i) The evidence for the suggestion that there is a relevant exception to the reflective loss rule in Malta which would apply in this case is at best exiguous, and not supported by the sources of Maltese law cited.

ii) The propositions put forward appear to rest on factual assertions which are not clear. It is not Sweden’s case that Falcon was some form of cipher or “sham creature”, and no allegations of wrongdoing have been made against its managers.

iii) The expert opinion proceeds on the basis that the transfers of assets to Falcon were void. However, this is not the basis on which Sweden has pleaded or argued its case, as Sweden confirmed.

iv) If Falcon is treated as a device whose existence should not affect the SJ Respondents’ liability to Sweden, Sweden’s argument that the introduction of Falcon leads to a change in the applicable law becomes correspondingly more difficult.

94. Further, Sweden’s solicitors obtained evidence at an earlier stage of the proceedings from ZammitPace, the Maltese law firm acting for KPMG in the proceedings commenced by Falcon in Malta. In a report of 20 February 2020, addressing possible lis alibi pendens arguments, ZammitPace advised:

“KPMG as Competent Person in charge of the Maltese Proceedings on behalf of Falcon and is appointed by and reports to the MFSA. Falcon is the Claimant in the Maltese Proceedings and in my opinion there is no basis under Malta law for treating the SPA, as sole non-founder shareholder of Falcon, as the ‘real party’ to the Maltese Proceedings”.

95. It is not easy to reconcile the application of the exception to the reflective loss put forward by Dr Zammit and Dr Xerri, with the fact that Falcon itself, and not Sweden, is the “real party” under Maltese law for the purpose of pursuing claims arising from the investments made in the Falcon phase.

96. For this reason, also, therefore, I am not persuaded that Sweden’s claims in these proceedings relating to the Falcon phase have been made out to the summary judgment standard.

CONCLUSION

97. For these reasons, Sweden’s application for summary judgment:

i) succeeds against Mr Ingmanson and Mr Bishop in respect of the Optimus phase in the amount of damages of $28,529,981, but fails against Mr Gergeo;

ii) fails against all SJ Respondents in respect of the Falcon phase.

CONTINUATION OF THE WFO

98. I am satisfied that the WFO should be continued post-judgment against Mr Ingmanson and Mr Bishop in respect of the liability I have found. The matters which persuaded me to grant the WFO on 28 February 2020, as set out in the judgment reported at [2020] EWHC 486 (Comm), continue to apply, save that Sweden has now established its case against Mr Ingmanson and Mr Bishop in respect of the Optimus phase.

99. I would like to conclude by expressing my profound thanks to the Swedish prison authorities for making it possible to hold this hearing.