Neutral Citation Number: [2020] EWHC 3450 (IPEC)

Claim No: IP-2019-000097

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE

Business and property courts of England and wales

Intellectual property list (ChD)

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY enterprise court

Royal Courts of Justice, Rolls Building

Fetter Lane, London, EC4A 1NL

Date: Wednesday 16th December 2020

Before :

Mr RECORDER DOUGLAS CAMPBELL QC

(sitting as a Judge of the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

B E T W E E N:

the janger limited

Claimant

- and -

tesco plc

Defendant

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

James St Ville (instructed by Irwin Mitchell LLP) for the Claimant

Adam Gamsa (instructed by Haseltine Lake Kempner LLP) for the Defendant

Hearing dates: 3rd - 4th November 2020

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - -- - -- - - - -

Judgment approved

COVID-19: This judgment was handed down remotely by circulation to the parties’ representatives by email. It will also be released for publication on BAILII and other websites. The date and time for hand down shall be deemed to be Wednesday 16th December 2020 at 1030am.

Mr Recorder Douglas Campbell QC:

Introduction

1. This is a case about garment hangers.

2. The Claimant (“Janger”) is the proprietor of GB 2 552 562 B entitled “A hangable garment hook”, filed on 17 February 2017. Three claims are in issue, namely claims 1, 4, and 5. I do not need to consider any other claims.

3. The Defendant (“Tesco”) is the well-known grocer and retailer of clothes in the UK. Tesco has used, kept, offered to dispose of and disposed of certain hangers known as the Meetick hangers. These acts are said by Janger to infringe the claims identified above.

4. Unusually, infringement is not in issue. Instead Tesco’s defence attacks validity on 2 grounds.

(a) First, it submits that claims 1 and 4 are anticipated by, alternatively obvious over, United States Design patent no. 378 167 in the name of Burnia J Jones, Jr (“Jones”) and that claim 5 is obvious over Jones. The title of Jones is “Clothes Hanger Holder”, and its single claim is for “The ornamental design for a clothes hanger holder, as shown and described”.

(b) Secondly, it submits that all claims are invalid due to the prior disclosure of a garment hanger known as the Globalhanger, which was designed by Mr Peter Greening of Global Hanger Solutions Limited (“GHSL”). Specifically Tesco submit that the Globalhanger was disclosed to Trevor Hatchett of Marks & Spencer PLC (“M&S”) at a meeting held on 1 October 2013 without any obligation of confidence. It is not disputed by Janger that the Globalhanger falls within claim 1, 4, and 5.

5. I had not previously heard of the term “clothes hanger holder” before this case, and neither expert said it was a commonly used one in the industry. It refers to a type of product which might be used to carry a number of clothes hangers, each of which might carry a garment. A salesman might use it to carry a number of such hangers together, or it might be used in the back of a car or lorry.

The witnesses

6. On behalf of the Claimant I heard oral evidence from Michael Bloomfield, Trevor Hatchett, and Mike Jones. None of the Claimant’s witnesses was criticised by the Defendant. I agree: they were all good witnesses.

7. Mr Bloomfield is the former Managing Director of GHSL. He held that position between June 2006 and August 2015. Mr Hatchett is the Packaging and Production Quality Lead for Clothing and Home Packaging at M&S. He has worked for M&S since January 2008. Their evidence went to the alleged prior disclosure and I will discuss it below.

8. Mr Jones was the Claimant’s expert. (He is not related to the Jones of the US design patent). He has a BSc in Product Design from the University of Central Lancashire. He started working for Mainetti, one of the world’s largest designers and manufacturers of garment hangers, in 1999 and worked there for 20 years. He was engaged full time on hanger design and the manufacture of hanger design projects. From 2016 to 2019, he was Mainetti’s head of design. He knew a great deal about hanger design and I found his evidence helpful.

9. On behalf of the Defendant I heard oral evidence from Peter Greening, Alan Wragg, and William Hunt. Mr Greening and Mr Wragg were not criticised as witnesses, although their evidence was disputed, but Mr Hunt was.

10. Mr Greening is a freelance designer to two companies, one of which (Meetick Hangers International Limited) supplies the Meetick hangers to Tesco. He was cross-examined about the 1 October 2013 meeting. Mr Bloomfield had given evidence that the idea for the Globalhanger design came from an early Janger hanger, but this topic was not pursued with Mr Greening and I will not consider it further.

11. Mr Wragg is Tesco’s Category Technical Director for clothing, a position he has held since 2010 although he started working for Tesco in 1999. He was not at the 1 October 2013 meeting but gave evidence about Tesco’s own approach to confidentiality in its dealings with its suppliers. He explained, and I accept, that whether Tesco’s own discussions with suppliers were confidential depended on the circumstances. He was also cross-examined about Tesco’s pre-action correspondence and about an error in Tesco’s disclosure statement. Without intending any disrespect to Mr Wragg himself, who did his best to help the Court, I did not consider his evidence was relevant to the matters I have to decide.

12. Mr Hunt was Tesco’s expert. He has a BA in Industrial Design Engineering from Central St Martin’s. He worked at Braitrim UK Limited, another major hanger manufacturer, from 1994 to 2006 as an Industrial Designer designing garment hangers and other devices used by the clothing industry. Some of the products he designed while at Braitrim appear on a wallchart, referred to as the 2007 Spotless wallchart. He produced 2 reports, one of 13 pages and another of 11 pages.

13. In Mr Hunt’s first report (see [25]) he said that the term “clothes hanger holder” as used in Jones was more likely than not a typographical error and should read “clothes hanger/holder”. This was despite the fact that Jones has less than half a page of text in which the term is used no less than 4 times. This evidence prompted Janger to conduct some research (see below) which confirmed that it was not a mere typographical error. Yet even then Mr Hunt clung to his original theory: see Hunt 2 at [36], first sentence. In cross-examination, Mr Hunt admitted that he had not read the text of Jones. In my view Mr Hunt was not as careful with this part of his evidence as he should have been. I think he realised this himself in the witness box.

14. The other major criticism of Mr Hunt was that his evidence on validity relied on hindsight knowledge of the Patent. There is something in this criticism too, although less than Janger suggested. One of the major arguments on Jones turns on whether the Jones “clothes hanger holder” is a “garment hanger” within the meaning of the Patent. It is not hindsight to consider what the Patent actually means by “garment hanger” before deciding whether Jones falls within the scope of that term. On the contrary, it is essential.

15. That said, some of Mr Hunt’s evidence was unchallenged and I can therefore rely on it. Janger did point out that Mr Hunt had left the hanger industry in 2006, but did not give me any specific reasons as to why this disqualified him from giving expert evidence.

The skilled addressee

16. The relevant legal principles are set out eg in Actavis v Eli Lilly [2017] UKSC 48.

17. It was common ground that the skilled addressee is a designer with experience of hanger design. Such a person would have a bachelor’s degree, most likely in Product Design or Industrial Design, and a few years’ experience in the hanger industry.

The common general knowledge

18. The law is well established. See Idenix v Gilead [2016] EWCA Civ 1089 at [70]-[72] (per Kitchin LJ, with whom Floyd and Patten LJJ agreed). I apply that approach.

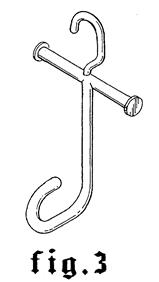

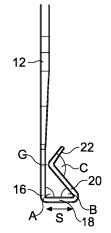

19. It was known that garment hangers had to satisfy a number of overlapping requirements, most of which are self-evident. For instance they should allow the garment to look good in stores, weigh as little as possible, minimise the cost of material, be robust enough for shipping, and permit fast hanging of the garments.

20. The industry was a small and specialist one. Mr Jones explained that there were only about half a dozen people based in the UK who were skilled garment hanger designers at the priority date.

21. A number of prior art designs were shown in the 2007 wallchart mentioned above. It was not established that any specific designs shown in this wallchart were themselves common general knowledge in 2017 but it provided a useful overview of the types of designs that formed part of the common general knowledge.

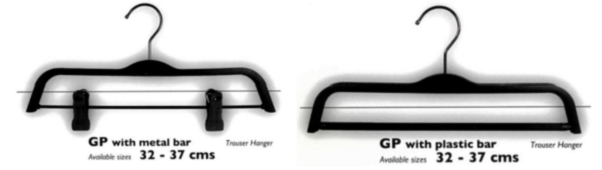

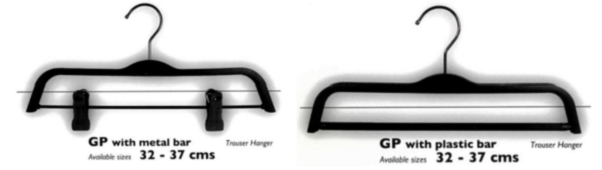

22. Two such types were clip hangers and letter box hangers, examples of which are shown below.

23. Another type of hanger was the S-hook. The S-hooks looked like butcher’s hooks and were used to hang garments such as jeans. The illustrations below show a Mainetti S-hook and some other S-hooks being used to hang jeans.

24. For any given design there might be trade-offs. For instance a design which made garments easy to load might not prevent them falling off during shipping (see eg the jeans above) in cases where the garments and hangers were being shipped together.

25. It was very common for hanger designs to have narrowed openings. More specifically, it was part of the common general knowledge to have notches and “lead-ins” in hangers used for garments with straps, such as lingerie or swimwear. The lead-in is a piece of plastic which guided or funnelled a garment on to parts of the hanger where it was held into position. Mr Jones exhibited an example of a bra hanger, reproduced below, which shows notches at the top and bottom on both sides with a lead-in at the very end of each notch. Another example of this type of product, minus a garment for clarity, is shown on the right below.

The Patent

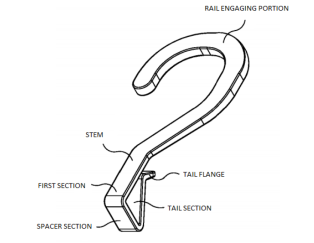

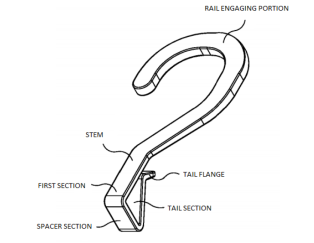

26. The Patent is entitled “a hangable garment hook”. It is 6 pages long, excluding the drawings and the claims. Most of what needs to be seen is apparent from the diagrams below. The one on the left was created by Mr Hunt by using the Patent’s own Figure 2, and then adding some names labelling the relevant parts. The one on the right shows a side view of the same thing.

27. The Patent opens by identifying the field of the invention. It says:

“The invention relates to a hanger, particularly a hanger for hanging garments, bags and/or accessories, and which may be employed in retail stores.”

28. It then sets out the background to the invention. It states as follows:

“A problem with many existing hanging devices is that if garments are removed from the hanger by customers they often do not rehang the garment properly when reapplying the hanger as many existing hangers are not easy to use to hang the garment properly such that it is neat, tidy and correctly merchandised. However, the hanger needs to be readily removable so that a customer can try on the garment before they purchase it.

Should a customer try on a garment but choose not to purchase it, it takes some time to rehang the garment and when such a process is rushed, the garment is often not folded properly and looks messy. Such a messy appearance can reduce potential sales and damage stock. In some stores, staff can be rehanging garments for a considerable period of time each day. Therefore, there is a need to reduce the time taken to rehang a garment.”

It then mentions various prior art solutions (eg those which connect to a garment through a belt loop, or which use a closable ring of plastic material) but suggests these have problems.

29. The next section is headed “Summary of the Invention” and starts with the consistory clause. Then the Patent goes on to say:

“The present invention provides a readily accessible open loop to engage with a loop of material on a garment. Thus, the garment can be readily affixed to, and removed from, the hanger. The loop is an open loop that is not fixedly connected to, and does not engage with, the stem, thereby allowing opening to be readily accessed to engage or disengage a garment. More preferably, a gap is formed between the tail section and the stem.”

30. The loop on the hanger is created by the opening between the end of the tail section and the first section in the above diagrams. It is this which engages with a loop of material on a garment. The gap, or spacer section, is then described as follows:

“Advantageously, the spacer section is substantially flat, or planar, and it may be an extended or an elongate portion on which the garment can rest, when in use. This provides a convenient location for the loop of a garment to rest and the spacer is sufficient length to allow the loop of material of the garment to lay flat, thereby not deforming the loop when the garment is on the hanger. Thus, the length of the flat section of the spacer on which the garment loop may rest may be more than 5mm in length to accommodate, for example, a belt loop.”

Thus the spacer section of the hanger is a flat portion on which the garment rests.

31. Various preferred features are described, including the following:

“It is advantageous that the opening between the tail section and the first section of the stem is less than half of the length of the spacer section and, particularly advantageous where the opening is less than a quarter of the length of the spacer section. Such a relationship reduces the risk of the garment disengaging from the hanger.”

This is related to the trade-off between garment loading and garment retention mentioned above. The smaller opening does reduce the risk of the garment disengaging, but it can make it harder to load the hanger in the first place. The Patent does not give any justification for the choice of “less than half” or “less than a quarter of the length”.

32. Then the Patent discusses the tail flange:

“Preferably, a tail flange is provided on the tail section and extends in a direction away from the stern and the spacer section. The tail flange is employed to provide a guide, or to create a funnel section, to guide garments into the open loop of the stem section more readily. This reduces the precision required by a user when affixing the hanger and they can simply slide the garment loop close to the hanger and the tail flange will guide the garment loop into the opening of the hanger.

33. Thus the teaching here is that the tail flange is used to provide a guide, or to create a funnel section, to guide garments into the open loop of the stem section more easily and thereby make the user’s job easier. It therefore compensates for making the opening narrower, and performs the same function as a lead-in.

34. At page 3, line 30 the Patent states as follows:

“The hanger is a garment hanger, although it may be used on accessories or bags.”

This is consistent with the passage relating to the field of the invention.

35. Next the Patent provides a brief description of the drawings and a detailed description of exemplary embodiments. One particular passage of interest is on p 5, and this states as follows:

“The tail flange 22 helps to guide the loop of the garment into the gap G by forming a secondary, guide wall that converges on the gap G. The tail flange 22 can also be used to open the gap G wider by putting pressure on the tail flange 22, for example by using a thumb, thereby allowing a user to more easily attach the garment to, or remove the garment from, the hanger 10.”

36. The first sentence refers to the same guide/funnel feature as is discussed above. The second sentence makes a different point, which is that the user can use his or her thumb to press on the tail flange 22 and thereby open the gap wider.

37. The ultimate purpose of this second feature is similar to the first, ie it allows the user to more easily attach or remove the garment. Mr Jones agreed that the lead-in shown in his example of the bra hanger could be used in the same way for the same purpose, although he said that this was not required. Thus although this second passage expressly refers to the use of the tail flange to make the gap G wider in the patented hanger, the lead-ins of the common general knowledge hangers could be used in the same way and for the same purpose for the corresponding gap in those hangers.

The claims

38. The case was argued on the basis of the “normal” interpretation of the claims, and there is no need to consider the doctrine of equivalents. See eg Eli Lilly v Genentech [2019] EWHC 387 (Pat) at [294].

39. Using the integers adopted in the pleadings, claim 1 is as follows:

[1] A garment hanger

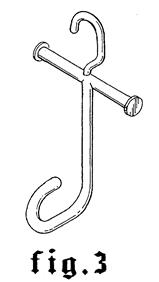

[2] having a rail engaging portion in the form of an arcuate hook

[3] and a stem, wherein, the stem comprises

[4] first section extending from the rail engaging portion,

[5] a spacer section extending substantially perpendicularly from the first section; and

[6] a tail section extending from the spacer section and directed towards the first section and/or the rail engaging portion,

[7] wherein the stem forms an open loop with an opening between the end of the tail section and the first section of the stem

[8] and wherein the rail engaging portion has a span for engaging the rail

[9] and the spacer section extends in a plane that is non-parallel with the plane of the span of the rail engaging portion.

40. The combined effect of integers [5] and [9] is that the spacer section extends substantially perpendicularly from the “first section”, ie from the part below the hook, in a direction which takes it out of the plane of the hook. Janger suggested in cross-examination that this made the claimed product a dramatic departure from what was available on the market as at the priority date, namely 17 February 2017.

41. The arguments of construction on claim 1 were as to what was meant by “garment hanger”, integer [1], and “rail engaging portion”, which appears in each of integers [2], [4], [8], and [9].

A garment hanger

42. Tesco submitted that a garment hanger is a product for hanging garments, and that it was enough that it was suitable for that role (citing Virgin Atlantic [2011] RPC 18 from [19]). I do not think it is necessary or appropriate to import the whole of the law about “for means suitable for” into a claim which does not contain the word “for” in the first place, but I agree that a garment hanger is a product for hanging garments. I also agree with Tesco that it need not be a commercially attractive or an optimal hanger.

43. Furthermore claim 1 is a claim to a product. I reject the idea that there is any sort of subjective element involved. Neither the user’s intention as to how he or she intends to use the product, or the name which he or she applies to it, changes its essential nature. A drinking glass in a window is still a drinking glass, even if someone puts the label “vase” underneath it.

44. In fact the teaching of the Patent goes a little broader than a product for hanging garments, since in two places it refers to hanging accessories or bags. This suggests that a wide, rather than a narrow, meaning of garment hanger is intended.

45. Finally the term “garment hanger” does not mean that the hanger must have arms, or shoulders (eg like a conventional coat hanger, or like a clip or letter box hanger). First, the claim does not require there to be any sort of arms or shoulders. The preferred embodiment does not have any arms or shoulders either. Secondly, one would not need arms or shoulders for hanging accessories, bags or (to use another example given by the experts) ties.

46. I am not sure that Janger ever actually said what the term “garment hanger” meant in the context of the Patent. Their argument was that whatever it meant it excluded a clothes hanger holder, in order to distinguish Jones. The implicit assumption is that the same thing cannot be both a clothes hanger holder and a garment hanger but I do not see why this follows. Any given product might not be optimised to perform both functions but that is another point.

47. Janger made some other submissions as to what was excluded from the term garment hanger, but these do not take matters further. For instance I agree with Janger that the mere fact garments can be placed on a chair does not make the chair a garment hanger, but the chair is not a hanger at all. Janger also suggested that a hook on the back of a door was not a garment hanger. I do not agree, given the claim and the nature of the preferred embodiment, but nothing seems to turn on it since neither Jones nor the Meetick hanger consists of a hook on the back of a door.

A rail engaging portion

48. The parties adopted similar approaches here. Tesco submitted that it meant, or at least included, an opening which could engage a rail. I agree. Furthermore this integer does not import any requirements about the size or even the shape of the rail on to which the relevant portion of the hanger engages. It has a broad meaning.

49. There was also a secondary argument about the words “extending from the rail engaging portion” in integer [4], but this is best dealt with in the context of Jones.

Claims 4 and 5

50. Claims 4 and 5 were for:

4. A garment hanger according to any preceding claim, wherein the opening between the tail section and the first section of the stem is less than half of the length of the spacer section.

5. A garment hanger according to any preceding claim, wherein a tail flange is provided on the tail section and extends in a direction away from the stem and the spacer section.

51. The only issue on claim 5 was whether the “tail flange” excluded the lead-ins of the common general knowledge. I agree with Tesco that it does not. The Patent explains the two functions achieved by the tail flange, but these are the same functions achieved by the lead-ins of the common general knowledge. No reason was given as to why the term “tail flange” per se would not include these lead-ins.

Jones

52. Jones has 4 figures but I only need to consider two of them since Figures 2 and 4 are mirror images of those shown below. The difference between Figures 1 and 3 is as regards the ends on the cross-bars and Figure 4 is a mirror image of Figure 3.

53. After the parties had exchanged expert reports, Janger found out some more information about the Jones product at www.hangerholder.com. This revealed that the term clothes hanger holder was not a mistake. Here are some of the relevant pictures:

54. The picture on the left shows the Jones product holding a hanger. The picture in the middle shows the woman using the cross-bars to hold the Jones product itself. The picture on the right is an enlargement of the one in the middle which shows the US design patent number for Jones. However, neither side suggested that this material should be used to interpret the disclosure of Jones itself and I shall not do so.

55. Janger also demonstrated that the prior art documents cited in Jones were mostly for carrying clothes hangers and that they used names such as ‘garment bag hook’, ‘Clothes Hanger Caddy’, ‘Hand tote device for garments on clothes hangers’ and ‘Hanger Holder’: see B5/16-22.

Novelty over Jones

56. The legal principles are well-established. In order to anticipate the claim, the prior publication must contain clear and unmistakeable directions to do what the patentee claims to have invented: see eg General Tire v Firestone [1972] RPC 457 at 485; Synthon v SmithKline Beecham [2006] RPC 10 at [20]-[22].

Claim 1

57. Janger submitted that Jones did not disclose integers [1], [2], [4], and [8]-[9] because it was not a garment hanger, did not have a rail engaging portion, and because it had a cross-bar from which the stem extended. I disagree on all 3 points, for the following reasons.

58. First, Jones does disclose a product for hanging garments, and thereby satisfies integer [1]. It might not be ideal, but one could hang eg the loop of a belt of trousers on the lower part, or for that matter accessories, bags, or ties. Mr Jones accepted that you could hang garments on it, although he said it would not be optimum for a retail store. The fact that it might be non-optimum for a retail store is neither here nor there, and nor is the fact that Jones chooses to call his product a clothes hanger holder.

59. Secondly, Jones discloses an opening which could engage a rail and thereby satisfies integers [2], [8], [9]: see the upper part thereof. It might not be ideal at this either, but that does not matter.

60. Thirdly, the fact that the Jones stem extends from the cross-bar does not mean that it ceases to have a first section extending from the rail engaging portion. No technical reason was given for supposing this to be the case. The first section is simply the first part of the stem, between the rail engaging portion and the spacer section. Jones discloses integer [4] as well.

61. Thus claim 1 is anticipated. It also follows that Jones discloses what Janger claimed was the dramatic difference between the Patent and commercially available products at the priority date, namely the out of plane hook. I say a little bit more about this below.

62. In order to test this conclusion, I ask myself whether Jones would have infringed the Patent if it had post-dated it rather than being made available to the public before. In my view it would. The fact that Jones is a clothes hanger holder would not provide a defence to an action for infringement of claim 1, nor would the fact that it falls short of being optimum for a retail store.

Claims 4 and 5

63. Claim 4 is not anticipated. The Jones diagrams are informative, but are merely schematic. It looks like the opening between the tail section and the first section of the stem (ie the gap) is less than half of the length of the spacer section (ie the bottom) but it is not unambiguous. Claim 5 is not even alleged to be anticipated. I therefore turn to obviousness.

Obviousness over Jones

64. The relevant legal principles were recently reviewed by the Supreme Court in Actavis v ICOS [2019] UKSC 15. I will not set them out here. Actavis confirms the desirability of using the structured approach set out in Pozzoli v BDMO SA [2007] FSR 37 at [23].

65. I have already set out the skilled addressee and the relevant common general knowledge above. I will now consider claims 4 and 5 separately.

Claim 4

Inventive concept of claim 4

66. The inventive concept of claim 4 is the combination of claim 1 plus the requirement that the opening between the tail section and the first section of the stem is less than half of the length of the spacer section (which I will call “the narrow opening” feature).

Differences between Jones and the inventive concept of claim 4

67. The only difference between Jones and the inventive concept of claim 4 is the narrow opening. I have already found that Jones discloses the subject matter of claim 1.

Viewed without knowledge of the invention as claimed in claim 4, is this difference obvious or does it require any degree of invention?

68. The purpose of the narrow opening is as I have explained above, a trade-off between making the garment easy to load but retained in place. No other purpose was identified. Nor was there said to be any magic in the choice of “less than half”.

69. Janger’s argument here relied mainly on the same argument I have already rejected, which was that because Jones disclosed a clothes hanger holder it could not be a garment hanger. From there Janger went on to argue that it was not obvious to introduce the narrow opening requirement either. In order to assess this latter point I turn to the evidence.

70. Mr Hunt’s evidence on obviousness over Jones was given on 2 bases: first, assuming that that the reference to “clothes hanger holder” was a typographical error, and the second assuming that it was not. I disregard his evidence on the first basis since the assumption is wrong. However his evidence on the second basis was not even challenged: see in particular Hunt 2 at paras [37]-[48].

71. Thus Mr Hunt’s evidence that holders for hangers were part of the common general knowledge of the skilled person, and hence part of the same family of designs as garment holders was not challenged: see Hunt 2 at [39]. Mr Hunt supported this by saying that he personally designed several such hangers, which were shown in the 2007 wall chart. So it is not as if garment hanger holders are a different species from garment hangers. They could be, and were in his case, made and designed by the same people.

72. Nor did Janger challenge Mr Hunt’s evidence that modifying Jones so that the opening was less than half of the spacer section would be routine given the trade-off between security of the garment and ease of hanging: Hunt 2 at [46]-[47]. This part of Mr Hunt’s evidence refers to garment hangers, despite it appearing as part of a passage dealing with Jones as a clothes hanger holder, but his logic applies equally well to a garment hanger holder since a similar same trade-off would apply there. In particular one would want the hangers to load on to the holder easily, but to stay in position during transport.

73. Mr Jones did not think that claim 4 was obvious over Jones, but his reasoning depended on his view that Jones was not a garment hanger within the meaning of claim 1: see Jones 1 at 151.1. Hence his comment at paragraph 151.2 that Jones “does not try to solve a problem of garments falling off or being knocked [off] a garment hanger”. He agreed there was a trade-off between security and ease of hanging and that it “would be obvious” to create the preferred ratio described in claim 4 if it turned out that there was a problem in practice: see Jones 1 at 164.4, and D2/24619-24713.

74. In my view claim 4 is obvious. Jones only just misses being an anticipation of claim 4 but it certainly discloses an opening in the relevant place which is narrower than the spacer section. The purpose of this narrow opening in Jones can only have been to stop things falling out. No other reason was suggested. It is therefore an example of the same trade-off mentioned in the Patent, but in the context of the Jones device. There would have been no invention in making the opening smaller than already shown in Jones and doing so would have produced a variant of Jones in which clothes hangers and/or garments would have been held more securely.

75. I have not needed to consider whether the idea of having an out of plane hook really would have been seen as being a dramatic departure from commercially available products, because they are not the starting point. It was not suggested that claim 4 was obvious over anything other than Jones, so it is not necessary for me to consider whether it would have been obvious to modify eg S-hooks, letter box hangers, or clip hangers in order to fall within this claim (or indeed within claim 1). However if it were, then this would presumably be an even greater spur towards making Jones into a more commercial product (since Jones already incorporates this dramatic departure) and this modification would become more obvious rather than less.

76. In many cases of obviousness the question arises as to why, if obvious, the invention was not done before. This was not explored in the evidence to any degree, although Mr Greening gave some unchallenged evidence to the effect that manufacturing an out of plane hook was more difficult: see Greening 1 at paragraph [13]. Since this was not explored I will say no more about it.

Claim 5

Inventive concept of claim 5

77. The inventive concept of claim 5 is the combination of either claim 1 or 4, plus the requirement that a tail flange is provided on the tail section and extends in a direction away from the stem and spacer section (ie the “tail flange” feature).

Differences between Jones and the inventive concept of claim 5

78. The only difference between Jones and the inventive concept of claim 5 is the tail flange. I have already found that Jones discloses the subject matter of claim 1 and that claim 4 is obvious.

Viewed without knowledge of the invention as claimed in claim 5, is this difference obvious or does it require any degree of invention?

79. The purpose of the tail flange is the two functions identified above, ie the guide/tunnel function and the ability to open up the space between the tail flange and the stem.

80. Mr Hunt’s evidence on this was not challenged either: see Hunt 2 at 48. He began by saying it was obvious to modify Jones to add the narrow opening, as explained above, and then added that after doing so it would be obvious to add a flange in order to improve ease of loading (ie to compensate for narrowing the opening). Again his evidence seems to focus on garment hangers, not on a clothes hanger holder, but the logic in each case would be the same.

81. Mr Jones’s evidence on this relied on it being non-obvious to add the narrow opening (see Jones 1 at 168.3) but I have rejected that. He also relied on the idea that the use of a tail flange in the manner claimed in claim 5 was not within the common general knowledge (ibid), although in his cross-examination Mr Jones conceded that both of the relevant functions of the tail flange were within the common general knowledge. His own picture of the bra hanger reinforced this. Mr Jones’s point was that these functions were not common general knowledge in the context of a hanger as per claim 1, but all he meant by that was that hangers as per claim 1 were not common general knowledge. His oral evidence ended up in a similar position to his evidence on claim 4, namely that one might not need the tail flange but that “it just depends on the situation”: see D2/24710-21.

82. In my view claim 5 is obvious as well. There is more distance between Jones and claim 5 than there is between Jones and claim 4, since claim 5 involves adding a new feature rather than merely extending a feature which is already present. However tail flanges were common general knowledge to the skilled addressee, albeit in the context of other types of hanger, as were the two functions thereof. There would have been no invention in adding a known tail flange to Jones to take advantage of the known functions thereof. It would improve ease of loading of clothes hangers and/or garments into the Jones device, just as was done for the same reasons in the prior art hangers.

83. Since claim 5 depends on claim 1 as well as on claim 4, it is not necessary to show that it would have been obvious to introduce both the narrow opening and the tail flange into Jones, merely the tail flange. It does not seem to me that anything turns on this. It would have been obvious to add a tail flange to Jones as it is to take advantage of these functions, and if anything more obvious to do so if the existing opening in Jones were to be narrowed further.

84. In closing, Janger’s counsel mentioned for the first time the possibility that the same issue might have been addressed in other ways not involving a tail flange (eg sideways loading of the hangers into Jones). This possibility was not put forward by either expert despite multiple rounds of evidence, followed by cross-examination. Hence there is no evidence about how practical it would have been. This does not matter since even if I assume that this option was also obvious, that does not make the incorporation of a tail flange into Jones non-obvious.

The Globalhanger disclosure

85. Upon reading the pleadings, it seemed to me that the only live disputes relating to this topic were (a) what was disclosed to M&S at the meeting on 1 October 2013 and (b) whether this disclosure was made without any obligation of confidence: see the list of issues at paras 2, 3.

86. In its evidence Janger sought to raise a further point, namely that what was disclosed was not enough in order to determine whether the product fell within claims 1, 4, and 5 of the Patent (ie that the disclosure was not enabling). I agree with Tesco that this argument should have been pleaded. It was not good enough for Janger to sit back and wait to see what the evidence established, since Tesco’s evidence was produced in response to the pleaded case. As things turned out this does not matter either.

Legal context

87. There was no dispute as to the law: see Megarry J in Coco v A N Clark (Engineers) Ltd [1969] RPC 41 at 47:

“First, the information itself ... must ‘have the necessary quality of confidence about it’. Secondly, that information must have been communicated in circumstances importing an obligation of confidence. Thirdly, there must have been an unauthorised use of the information to the detriment of the party communicating it.”

88. Nor was it disputed that the approach to determining whether the information was communicated in circumstances importing an obligation of confidence is an objective one which depends on the circumstances. Arnold LJ (with whom both Phillips and Lewison LJJ agreed on this point, see [170] and [174]) put it as follows in Racing Partnership Ltd v Sports Information Services Ltd [2020] EWCA Civ 1300 at [79]:

79. So far as the law is concerned, neither side took issue with the test that I derived from the authorities in Primary Group (UK) Ltd v Royal Bank of Scotland plc [2014] EWHC 1082 (Ch), [2014] RPC 26 at [223], which was approved by this Court in Matalia v Warwickshire County Council [2017] EWCA Civ 991, [2017] ECC 25 at [46] and referred to by the judge at [135]:

“It follows from the statements of principle I have quoted above that an equitable obligation of confidence will arise not only where confidential information is disclosed in breach of an obligation of confidence (which may itself be contractual or equitable) and the recipient knows, or has notice, that that is the case, but also where confidential information is acquired or received without having been disclosed in breach of confidence and the acquirer or recipient knows, or has notice, that the information is confidential. Either way, whether a person has notice is to be objectively assessed by reference to a reasonable person standing in the position of the recipient.” …

What was disclosed at the meeting?

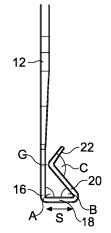

89. In December 2012 Mr Greening produced his Globalhanger design using CAD software called “Freehand”. It does not matter whether the inspiration for this was a meat hook used by River Island (as Mr Greening said) or an early Janger design (as Mr Bloomfield said). The file properties for the relevant CAD file show that it was created on 11 December 2012 at 11.45 and last modified on 19 December 2012 at 09.47: these dates were not challenged. On 19 December 2012 Mr Greening also outputted a PDF showing the design. This was his practice at the time, because printing the PDF tended to produce a better result on his printer than printing directly from Freehand. The relevant PDF has 2 images and looks like this:

90. Mr Greening’s idea in December 2012 had been to show this design to River Island, but they were not interested. Nor, as it turned out, were other retailers such as Sports Direct or Monsoon. He decided to show it to M&S instead, to see if they were interested. It took some time to set up a meeting with M&S, but it eventually took place on 1 October 2013 in M&S’s head office in Paddington, London. Only 3 people were present (Mr Greening, Mr Bloomfield, and Mr Hatchett).

91. Mr Greening was the only witness to remember this meeting in much detail. He said it was held in a large room in the basement having a large meeting table and 20 or so chairs. The main purpose of it was to show M&S some new ranges of knitwear and lingerie hangers but he also remembered showing Mr Hatchett a printout of the PDF reproduced above. Specifically, Mr Greening slid it into the middle of the 6 foot wide meeting table for 1 or 2 minutes so that Mr Hatchett could see it, although Mr Hatchett did not pick it up. Mr Greening added that he would also have talked about it and described it. Mr Greening remembered the meeting because he felt that having a meeting with a retailer as large as M&S was a great opportunity for a very small company.

92. Mr Bloomfield also remembered attending the meeting on 1 October 2013, and he made the same point about it being a good opportunity for a small company. He did not remember showing Mr Hatchett the Globalhanger design. This is not surprising because when Mr Bloomfield was shown the Globalhanger design in the context of these proceedings, he did not immediately recognise it then either. He only remembered the Globalhanger design after being prompted by the documents which Mr Greening subsequently exhibited.

93. Mr Hatchett had no recollection of either the meeting or seeing the product. He had attended many such meetings over the years.

94. I prefer Mr Greening’s evidence as to what was disclosed at the meeting. Furthermore such contemporaneous documentation as there is tends to support his recollection, as do the dates of the electronic documents (ie those of the Freehand CAD files and the PDFs). For instance Mr Bloomfield sent Mr Hatchett an email dated 1 October 2013 and timed at 18.13 as a follow up to the meeting. In it he refers to the “jeans hanger”, which was the term used to describe the Globalhanger, so the product must at least have been mentioned at the meeting. It is true that Mr Bloomfield did not specifically say in this email that the PDF was shown to M&S, but it would be odd if it were not. At this stage there was no model of the Globalhanger, so no physical sample could be shown, whereas the PDF was available and was a much better way of explaining the proposed product to M&S than a mere oral description would have been. Having shown M&S the PDF, I agree it is likely that Mr Greening would have explained it to them as well and I find that he did.

95. As I have already said, the argument about lack of enablement is not open to Janger. However it does not run on the facts anyway. The design is not a complicated one. It seems to me that Mr Hatchett (a professional who had been in the industry for many years) would have been able to understand its nature from looking at the 2 diagrams contained in the PDF, even without additional explanation from Mr Greening. Mr Hatchett gave no evidence to the contrary.

Was this disclosure was made without any obligation of confidence?

96. The starting point is that this was a meeting between a supplier (represented by Mr Greening and Mr Bloomfield) and a purchaser (represented by Mr Hatchett) of an as yet uncommercialised product. As I have said the meeting took place in a basement in M&S’s head offices, not in a public place. These factors are all consistent with the disclosure being confidential.

97. As against that, there was no express discussion of confidence nor had any NDA been signed. However Mr Greening, Mr Bloomfield and Mr Hatchett all agreed that it would have been pointless to have asked customers to sign NDAs before meetings because they would not have signed them. The meetings would either not have happened, or been delayed while customers consulted their legal departments (which the customers would not have wanted to do). In closing, Tesco accepted that the absence of an NDA was not the end of the story.

98. Mr Green gave evidence that in his view the meeting was non-confidential and I accept that this is his view. However this evidence was undermined by his reluctant acceptance that Mr Hatchett would not have expected Globalhanger to disclose what was discussed in the meeting to third parties. Mr Greening also agreed that although he discussed a new knitwear hanger that he had recently developed for River Island at the meeting, he did not show samples of that to M&S because it was not in stores yet and “that was confidential with River Island”. Thus even Mr Greening accepted that some things about the meeting were confidential.

99. Mr Bloomfield was firm that the meeting was confidential. Indeed he said that M&S treated all meetings with suppliers as confidential, agreeing with Mr Hatchett on this point. He made the same distinction as Mr Greening did about the River Island knitwear hanger being confidential until it was in store. He said that he would not have been at all happy if a customer had taken a new idea or design and had it made by another supplier. In cross-examination he agreed that he would expect unregistered design rights to protect Globalhanger against the copying of its design in such a situation, but I regard that as being a separate point. The existence of laws against copying does not mean that the disclosure itself must have been non-confidential.

100. Mr Hatchett was also firm that any meeting with suppliers was private and confidential. He said he would not have considered it acceptable for M&S to do whatever it liked with the design. Both of these points are general but no reason was given as to why they would not apply to this particular meeting. He also agreed that he would not have had the product copied, but again I regard that as a separate point.

101. I find that the disclosure was made under conditions of confidence. I particularly rely on the circumstances of the meeting itself, and on the evidence of Mr Bloomfield and Mr Hatchett (who were at that time on opposite sides). It is true that I preferred the evidence of Mr Greening to theirs on the subject of what was disclosed, but this does not mean that I also have to prefer Mr Greening’s evidence on the subject of confidentiality. In any event Mr Greening’s evidence about confidentiality was equivocal and not such as to displace this conclusion.

Conclusion

102. In summary:

a) Claim 1 of the Patent is anticipated by Jones.

b) Claims 4 and 5 are obvious over Jones.

c) The Globalhanger disclosure consisted of the 2-image PDF shown above, supplemented by an oral description thereof from Mr Greening.

d) The Globalhanger disclosure was made under conditions of confidence.

103. I will hear counsel as to the form of order I should make.