BAILII is celebrating 24 years of free online access to the law! Would you

consider making a contribution?

No donation is too small. If every visitor before 31 December gives just £5, it

will have a significant impact on BAILII's ability to continue providing free

access to the law.

Thank you very much for your support!

[New search]

[Printable PDF version]

[Help]

Ronald P. Loui

|

Table of Contents:

|

Cite as: R. P. Lou, "A Modest Proposal for Annotating the Dialectical State of a Dispute", (2008) 5:1 SCRIPT-ed 176 @:

http://www.law.ed.ac.uk/ahrc/script-ed/vol5-1/loui.asp

Download options |

|

|

| DOI: 10.2966/scrip.050108.176 |

|

© Ronald P. Loui 2008.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Licence.

Please click on the link to read the terms and conditions.

|

1. Introduction

This

essay reports on the evolution of our computer-supported argument

diagramming and argument visualisation practices, as scholars of

argument, and also as computer scientists interested in supporting

the diagramming of argument. We begin with the Toulmin diagram,

describe efforts to avoid boxes and arrows by using encapsulation,

and efforts to depict the logic of legal argument from precedent.

Our aim is to provide a theory of argumentation and a theory of

legal precedent, and to provide visual correspondences for the

logical rules. It is not our principal aim to provide tools for

persuasive use, e.g., in a court of law. In the end, new

possibilities for using text decoration and markup, dynamic text

animation and interaction, and visual metaphor are envisioned. The

possibilities are so rich that the final examples border on satire.

2. Toulmin

My

starting point is the Toulmin diagram for visualising the structure

of defeasible arguments. But I have some reluctance because I

believe that this Toulmin kind of argument-diagramming is of limited

relevance to those who have practical persuasive legal needs. The

dialectical diagramming that my colleagues and I discuss in the

theory of argumentation, after Toulmin, is mainly a device for

elucidating logical structure. Our uses of these diagrams are for

theorising, not persuading.

In

an earlier paper with many co-authors,1

I referred to Toulmin diagrams as “a spaghetti of boxes and

arrows.”2

Many people in the CSCW (computer-supported collaborative work)

community had been writing on the user interfaces that they had

created based on Toulmin's box-and-arrow diagram, and there seemed

in the early 90’s a plethora of programs available to support

the manipulation of such box-and-arrow diagrams. Of course, one

draws a Toulmin domino when one wants to connect the supporting

claim to the claim it supports, and there is nothing wrong with one

Toulmin domino (three or four boxes and two or three arrows) by

itself. The problem is when many Toulmin dominoes are connected.

Since there is no prescription for the layout of the various boxes

and arrows, one must rely on the discipline of the user to create a

visually understandable diagram. As boxes and arrows proliferate,

it is not clear whether even the most disciplined arrangements of

Toulmin are cogent, or even comprehensible.

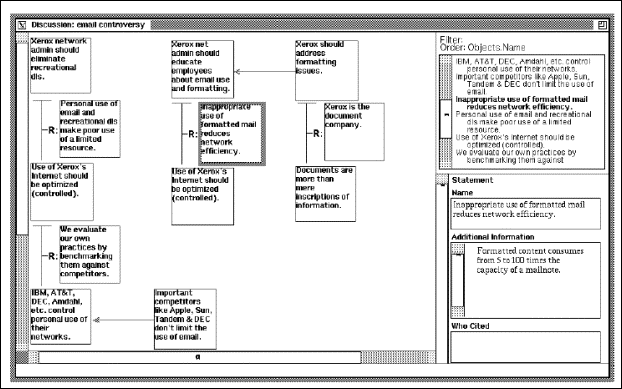

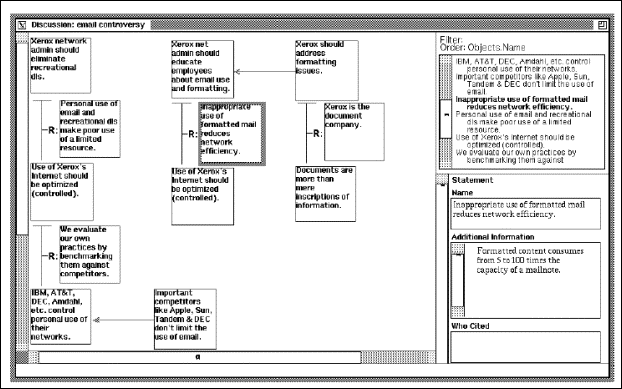

(from

Marshall)3

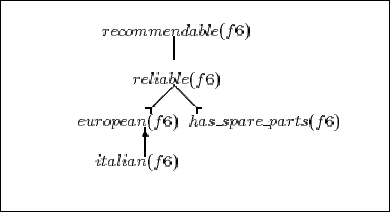

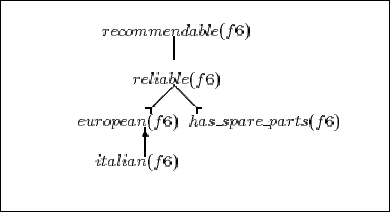

Meanwhile,

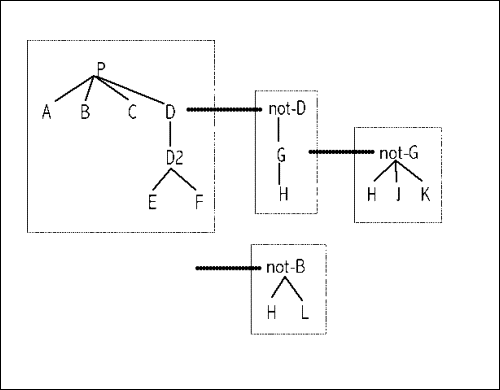

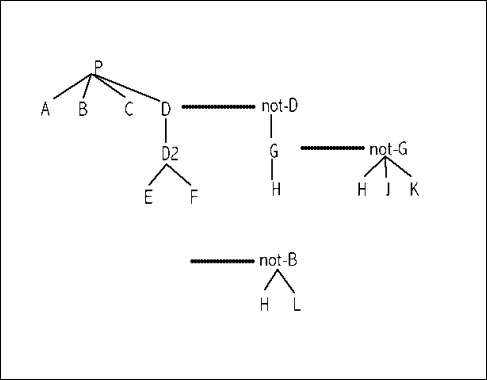

we had been diagramming arguments as trees, where the main claim of

the argument sat at the root of the tree, and the unsupported claims

sat at the leaves of the tree. (Trees were drawn with the root at

the top of the page, as computer scientists prefer.) A defeasible

connection between the children of a node and the node was made

implicitly. Toulmin instead would make a box that explicitly stated

this defeasible connection. By convention, if a node labeled p had

children labeled a, b, and c, then the required logical connection

was “if a, b, and c, then defeasibly p.” This was

perhaps the most common diagramming of arguments in the literature

in the late 90’s.

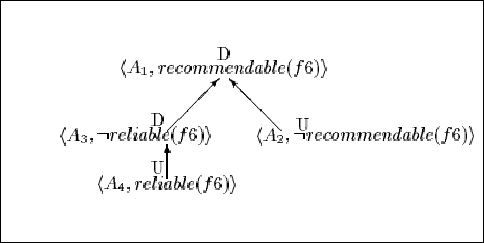

As

several arguments might particpate in a dialectical structure, where

one argument countered another, and a third countered it in turn,

seeking to reinstate the first argument, we would draw a second tree

showing the relationships between the arguments. Some would call

this the meta-argument tree, or the inter-argument tree, because it

showed how the arguments related rather than how the arguments were

constituted.

(from

Chesnevar)4

My own

preference was to combine the two diagrams, so that dialectical

relevance had a left-to-right discipline, and support was top-down.

Alternate arguments would also be listed top-down, but would not be

confused with support since each alternate argument would be its own

tree, connected within itself, but not connected to the other tree.

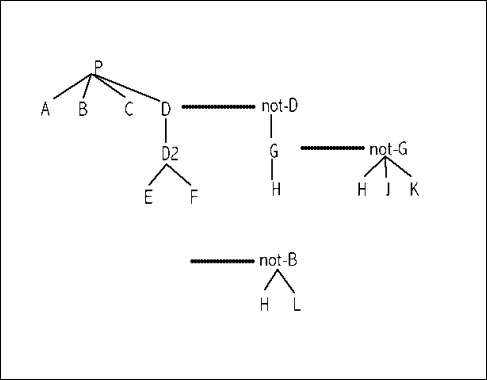

If one

insisted on comparing this to a Toulmin diagram, there were several

differences, all working in our favor and against Toulmin. First,

the largely redundant warrant and backing boxes would not be

explicitly shown. If an attack were made against a warrant, then

the warrant could be added at that time, or a counterattack would

simply be aimed at a link instead of a node. Nothing prevented

putting the names of cases or statutes on links, for example, and

warrants are often citation references rather than textual

statements. In any case, it was useful not to double the number of

boxes unnecessarily.

Second,

the arrangement into columns was a required part of our regimen.

Alternate columns would represent pro and con, so that any argument

in the second and fourth columns would presumably be adversary to

the position taken in the first column. Reading left-to-right would

reconstruct the dialectical dialogue in a logically useful way.

Third,

there was no explicit requirement that a counterargument link to the

exact node that was its logically contrary proposition or claim.

This could be done, but indeed would promote spaghetti. It was

sufficient, it seemed, to link the argument to its preceding column,

wherein one would find the object of the argument’s attack

(possibly with some effort). Since the number of arguments in a

column and the number of claims in an argument presumably would not

be too large, the connection could be made easily simply by visually

scanning for a negation. Even without locating this contrary

proposition in the prior column, it was knowable simply by negating

the claim at the root of the counterargument tree. Indeed, the

heavy dotted line served as much to indicate a new, alternate

attack, as to indicate, redundantly, that its relevance depended on

something claimed in the prior column.

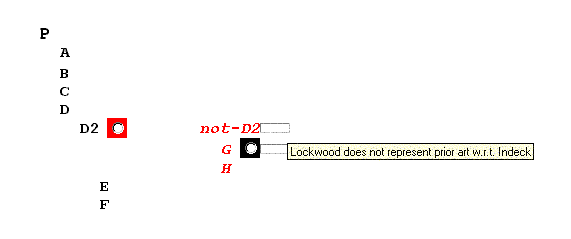

While

this style of recording dialectical structure was intuitive, it

actually clashed with the conventions of Rescher5

and the dialogue logicians, who preferred dialogical time to run top

to bottom, and to intertwine support, challenge for support, and

rebuttal. The logical exchange under Rescher would appear as:

|

PRO

|

CON

|

|

P

|

why

P?

|

|

A,B,

C, and D

|

why

D?

|

|

D2

|

why

D2?

|

|

E and

F

|

not-D

|

|

why

not D?

|

G

|

|

why

G?

|

H

|

|

not-G

|

why

not-G?

|

|

H, J,

and K

|

not-B

|

|

why

not B?

|

H and

L

|

It is

compact and can be written without graphical artifacts, but it does

not display the argumentative structure, nor even indicate whether a

move is sufficient. Rescher-form is in some sense the textual

locutionary form that the Toulmin diagram and all subsequent

diagrams attempt to compile into a more visually scannable,

pictorial form.

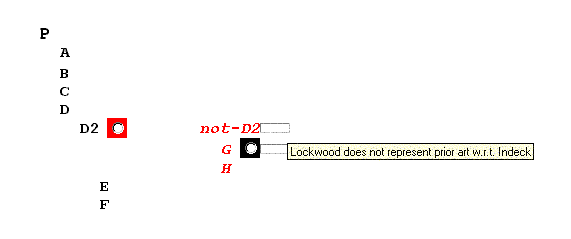

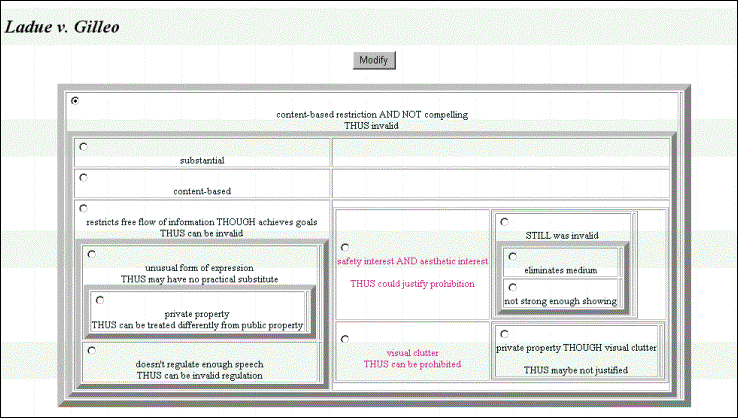

3. Encapsulation

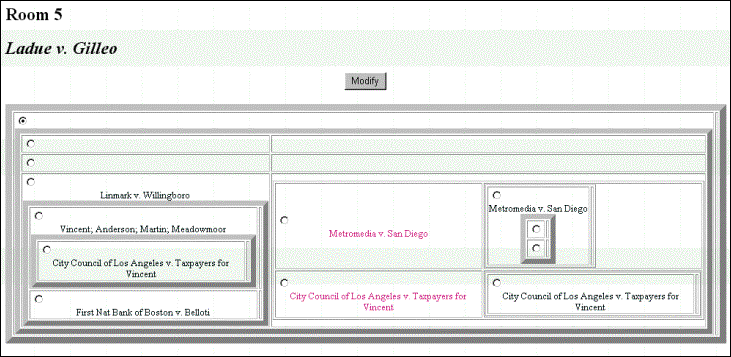

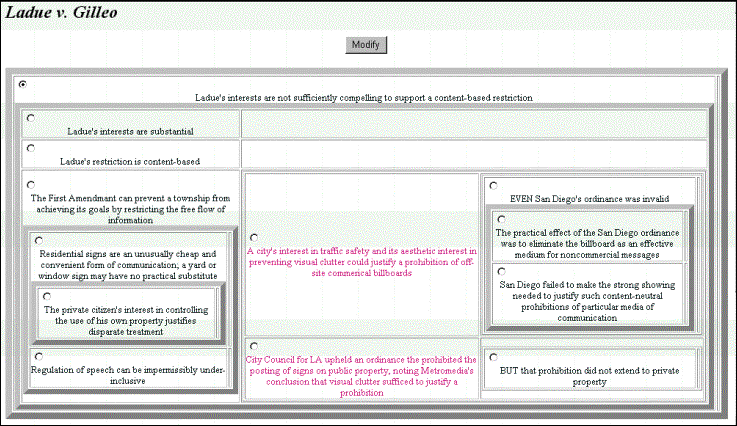

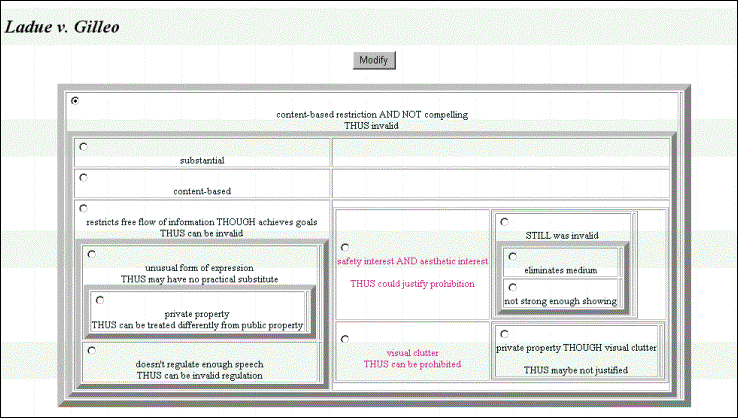

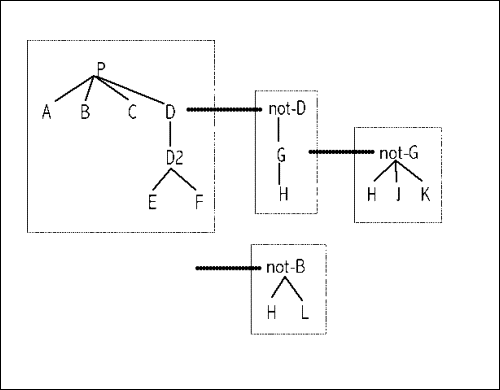

With the

advent of HTML, and inspired by the encapsulation of dialogues into

separate windows in computer GUI’s, we proposed simplifying

the diagrams further by removing all of the arrows. Support

relations would be implicit in the narrowest containments. All

containments after that would be of dialectical significance:

left-to-right for countering, rebutting, or undercutting;

top-to-bottom for alternate attacks of the same argument.

We even

proposed several views of arguments in this encapsulated form, where

one view gave the authorities of the claims, another gave a

paraphrase, and yet another gave a simplified logical form.

(from

Loui)6

But we

were crestfallen to realise that this form derives much of its

intuitiveness from the simple two-column outline form that is

familiar to high school debate participants.

For

example,

could be

written as

|

P

A

B

C

D

D2 not-D2

E G

F H

not-G

H

J

K

|

with no

loss of visual clarity.

This two

column form, “debate-form,” is not entirely satisfying,

as here it permits the lines for E and F's support of D2 to collide

with the lines for G and H’s support of not-D2. E and G share

lines, but their sharing has a different semantics from D2 and

not-D2 sharing a line. Where would a counterargument against E be

placed in this scheme? Moreover, the semantic overloading of the

line is exacerbated if we permit the third column and make no

provision for overlapping lines (E bears no relation to not-G, and

they share a line):

|

P

A

B

C

D

D2 not-D2

E G not-G

F H H

J

K

|

But the

reality is that the semantics of boxes within boxes is not so

transparent, and strict adherence to too many encapsulation rules

can actually decrease comprehension. The main advantage of the

boxes is that they permit a rotation from top-down to left-right for

lists of supporting propositions.

For the

diagram,

the

equivalent naive outline,

|

P

A

B

C

D

D2 not-D2

E G not-G

F H H

J

K

not-D2

H

L

|

is really

equally useful, if a bit ad hoc. And any attempt to clarify the

semantics of a line by imposing a push-and-pop spatial grammar

(e.g., the left-hand-side contiguity always defers to the

right-hand-side, during a counterargument) simply ruins the visual

appeal. The proper rendering, while preserving line semantics,

decreases density and reduces juxtaposition within arguments, thus

increasing scan effort:

|

P

A

B

C

D

D2 not-D2

G not-G

H

J

K

H

not-D2

H

L

E

F

|

These are

exactly the considerations that first led to our adoption of

encapsulation.

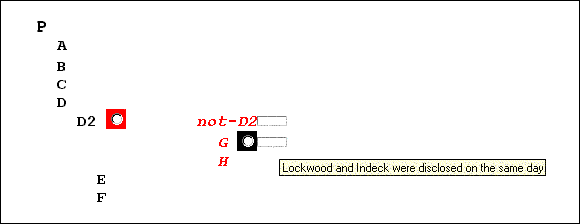

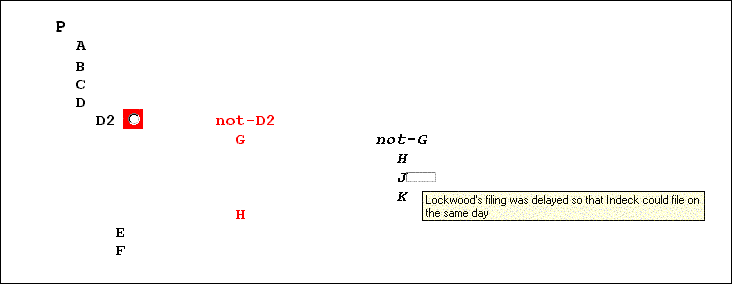

4. Web

Markup, Dynamics, and Animation

We are

now all familiar with the font control and dynamics of HTML, and the

possibilities for rendering argument are dizzying. Not only did we

use color to differentiate PRO’s and CON’s positions

above, but we could have used size and style, face and font-weight

as well. All of the original CSCW argument systems were precursors

of hypertext systems, so their authors envisioned actions of hiding

and unhiding upon user action.

For

example, the outline form above seems not so sparse when

counterarguments can be hidden or restored from hiding. Thus,

|

P

A

B

C

D

D2

E

F

|

might

display the main argument, whereupon clicking on the box next to D2

exposes the argument for not-D2, and further options for exploring

counterarguments.

|

P

A

B

C

D

D2 not-D2

not-D2

G

H

E

F

|

Interface

dynamics might include a mouseover or pop-up window for viewing

longer forms of the claim, or viewing the authorities of the

defeasible rules when mousing over the “links”.

In the

extreme, animations could be used, which would be difficult to print

in a paper such as this, even with screen captures. Animations

could show not only the historical development of the dialogue or

its dialectical structure; animations could also be used to show the

differing views of the state of the dispute, especially as

participants were willing to accept certain assertions,

presumptions, or defeat relations among competing arguments.

5. A

Plea for Structure over Style

No doubt,

the enterprising software interface designer has already thought of

connecting Microsoft Word functions and Adobe Photoshop tools to the

layout of arguments. Why not check the spelling and grammar? How

about smart quotes and a minimum font size?

There is

a fine line between aiding the thought process that underlies the

formation of rational beliefs, and the markup of text for its own

sake, or for mainly stylistic purposes. Of course, persuasion may

indeed at times require style. It is simply good practice to be as

clear as possible, and style helps. Perhaps the rhetorical desire

to produce multi-column aligned outlines would eventually be

satisfied by authors of PowerPoint providing some kind of columnar

text support for PRO/CON presentations.

Our real

interest in diagramming arguments derives from a desire to

understand structure as sophisticates. It seems our natural

obligation to offer symbolic regimes that sometimes go far beyond

the work-a-day visualisations. It would be folly to impose complex

structure on all argumentative forms. Even when the argument could

be diagrammed so as to expose inherent specific structure, the

academic must recognise that the practitioner need not do so. Even

when the user could use a template with more numerous

well-formedness constraints, the programmer must recognise her right

to use a simpler template. Still, our job is to invent those

templates.

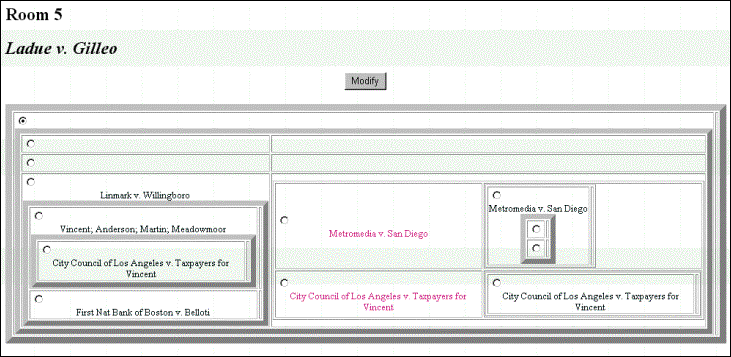

Here are

two forms that derive from the analysis of legal reasoning from

precedent. These are simple diagrams, but have had no real hearing

in the community of those who like diagramming.

The

first is the idea of Kevin Ashley, in HYPO.7

The idea begins simply enough: a present case is related to a

prior case by the enumeration of its similarities and

dissimilarities.

To

argue P on the basis of a past case exhibiting A, B, C, and D, one

need only remark that the current case has A and B in common, has C

as a distinction, did not report on D, and has an added fact of

possible relevance, E, that was not reported in the precedent. We

can find this basic idea in Raz,8

complete with letters A through E.

|

PrecedentCase

P

A

B

C

D

E |

CurrentCase

P

A

B

not-C

|

Without

going into too much detail, Ashley proposes an improvement of this

model for the restricted domain of reasoning about trade secrets

violations. He manually determines the dimensions along which

precedent cases and current cases may be compared for similarity.

He identifies each dimension as inherently pro-plaintiff or

pro-defendant so that reasoning can be augmented by dimensions, or

factors, that are not present in past cases.

The

result is a “claim lattice,” which is intended to show

the most on-point cases for plaintiff and defendant, based on

subset-relations among factors and the inclusion of additional

pro-plaintiff factors by the plaintiff, the omission of additional

pro-defendant factors by the plaintiff, the inclusion of additional

pro-defendant factors by the defendant, or the omission of

additional pro-plaintiff factors by the defendant.

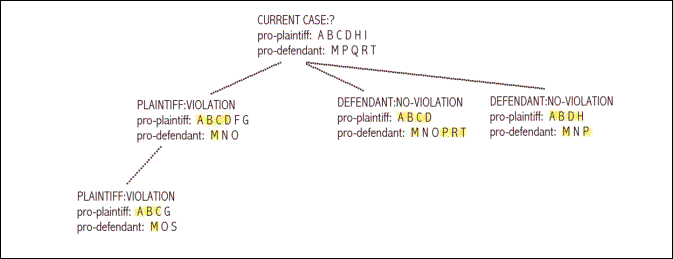

The

second template, or argument form, is the generalisation and

possible improvement of Ashley’s analysis, according to my

co-author, Jeff Norman, and myself.9

(This in turn may have been improved by Prakken and Sartor,

depending on what you think of analogies that are based on quite a

bit less similarity.10)

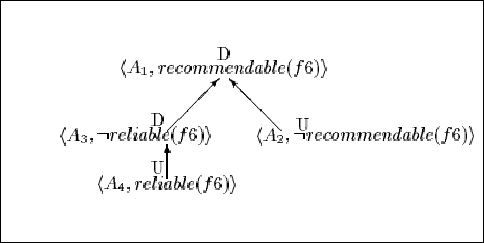

The main

idea here is to record the actual disputation tree from the past

case. An attempt to make use of a past case’s argumentation

is not just a listing of similarities, but a recall, re-enactment or

re-citation of the past arguments, to the extent that they can be

made in the current context. The synthetic contribution of the

prior case is the judicial decision that one argument defeated

another in the past case; hence, that same argument should defeat

the same counterargument in the current case, all things being

equal. However, if the past case’s main argument survived a

counterargument in the presence of a reinstating argument, and if

that reinstating argument is not available to the arguers of the

current case, then the authority of the past case is dubious.

What can

be visualised in this scheme are the past relationships among

arguments, and the current context’s ability to recall each of

those arguments, in part or in whole.

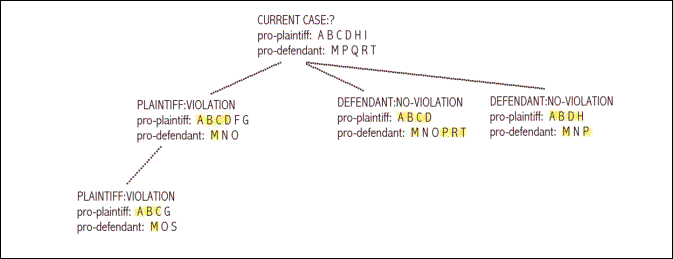

Here,

Precedent1 and Precedent2 appear to conflict over the conclusion of

Q in the current case. But the relevant similarities are not “A

B C D H J” versus “A B C E H M P,” which is an

indeterminate contest. The relevance of Precedent1 is that the “A

B C for Q” argument can be made. The counterargument that was

disfavored in Precedent1 is irrelevant in the current case because C

is not a current issue. Meanwhile, Precedent2 contains three

arguments, all of which can be made in the current fact situation,

and the argument for Q in Precedent2 is actually stronger than the

argument for Q in Precedent1. Nevertheless, at least in the context

of the disrupting argument “P for not-F,” the “A B

C E H for not-Q” argument was preferred in Precedent2. Thus,

Precedent2’s decision is authoritative here.

Perhaps

not so many case-based analogical arguments in the real world can

benefit from this kind of analysis, but I believe this kind of

argument diagramming, and the ambition to provide a calculus of

rationality, should not be lost as we see stylistic markup

proliferate among GUI tools for argumentation and cooperative

problem solving.

No

less a figure than Cass Sunstein pronounced HYPO to be inadequate as

an account of general legal analogy, at a conference sponsored by

Chicago Law Review students about a decade

ago.11

However, all of his concerns appear to my eyes to be addressed in

this deeper, argument-based model of the case. I do look forward to

legal scholars’ reactions to this subsequent modeling of the

logic of analogical reasoning. It has been almost fifteen years

since we proposed it, and HYPO itself is now over twenty years old.

It is a bit unfair to be looking at first generation models when

judging the entire AI and Law field.

6. Jonathan

Swift’s Modest Proposal

The

title of this talk contains the phrase “Modest Proposal,”

and there is a certain obligation to live up to Jonathan Swift’s

legacy.12

If there were something as outrageous as the famine of Irish

families in the world of argument visualisation, I would not

hesitate to stryke a satyrical tone. Perhaps if a generation of

lawyers had grown too enamored of Toulmin spaghetti diagrams, it

would be high time to suggest that we feed them a carb-free diet of

old-fashioned prosodic meat.

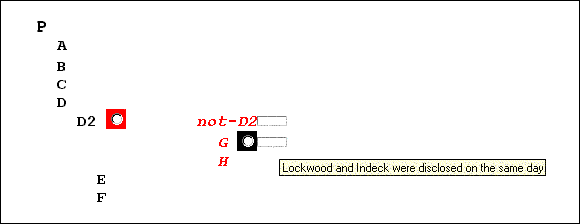

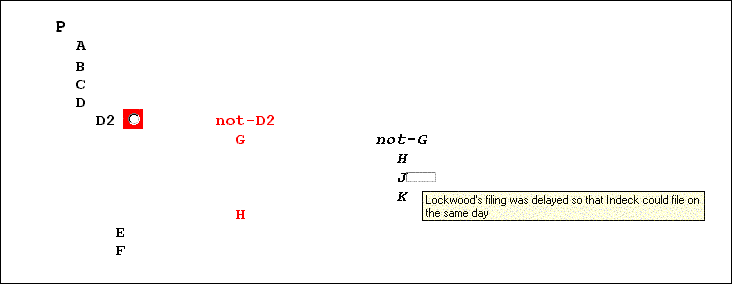

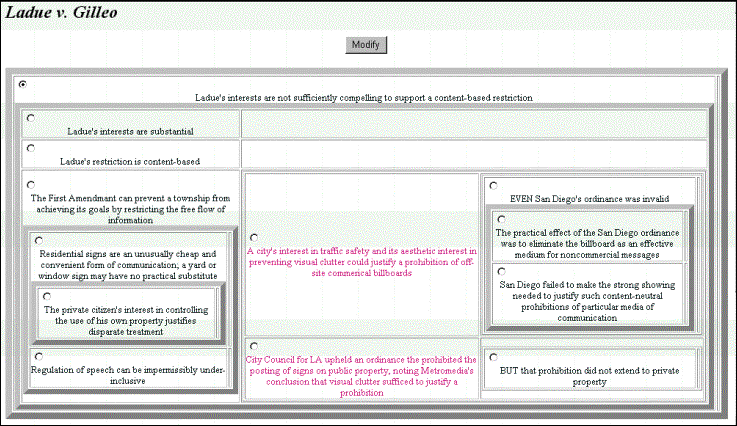

I had in

mind the unambitious annotation of an argument with the

warrant-status of all hidden arguments: red for a defeating counter

argument, pink for an interfering counterargument, pale pink-gray

for a defeated putative counterargument, black for an effective

reinstater, and gray for an ineffective putative reinstater.

Parentheses could be used to group the dialectical chains. D2 below

has a putative interferer that is defeated by a reinstater, but also

has an actual interferer with no rebuttal.

I have

indicated the warrant status of P with a gray surrounding box

instead of a black surrounding box because of the existence of the

unrebutted interferer. Visually, one can see immediately that this

is an argument supported on four main points, with one deep

(potentially weak) chain, where a counterargument has been rebutted

and another counterargument has not been.

But

thinking further, and a bit lightly, about how arguments could be

annotated based on their warrant status and apparent strength, I am

happy to suggest the following markup.

Here is

how you would indicate that an argument is little tested, but

inherently sound, has unusually wide appeal, and is probably an

argument that you would not want to have to defeat.

|

P

A

B

C

D

D2

E

F

|

|

Here is

an argument you have been waiting to make for some time, which you

expect would be a very good argument, that is, if there isn’t

a better argument to be found; and it is a familiar argument that

has survived many pointed attacks in the past.

|

P

A

D

D2

E

F

|

|

And here

is an argument that you just do not want to be making, an argument

that many may have made in the past with good intentions, an

argument that derives from a very strong precedent, but an argument

that has far too many points that are now simply indefensible.

|

not-P

C

D

F

|

|

Finally,

this is a fantasy view of how the dialectical state of longstanding

and well-understood arguments might be visualised, taking mainly

into account the potential strength of each.

7. Conclusion

We began

wanting only to improve on Toulmin diagrams by using encapsulation

instead of boxes and arrows (the same basic idea is used in any

Window-based graphical user interface). The same organisational

components were found to be available to highly disciplined

multi-column outline forms, where indenting with vertical

progression indicated subordinate support, and horizontal

progression indicated counterargument. These diagrams were

difficult to read, however. Part of what made these diagrams

unwieldy was their inability to hide uninteresting parts of the

dialectical state. It was then suggested that dynamics could be

used to open and close argument details, in the same way that users

interact with folders and subfolders of files in many common

software programs today. There were suddenly many possible ways

that interaction could alternately hide and reveal information.

More interestingly, the graphical object used to summarise a hidden

argument could convey information about the argument’s force

or validity: a consistent coloring of red for undefeated arguments

and black for defeated arguments could be used, for example.

Meanwhile, we noted that there were many interesting structural

devices, corresponding to logical constraints of specific argument

forms, that should be considered in the diagramming of arguments.

To ignore structure at the expense of graphical devices seemed an

unending walk into the world of text decoration, even web design.

Finally, we suggested, half-satirically, that a more cogent and

powerful visual shorthand could be found in simple metaphors to

politics and other orders of combat.

*

Professor in Computer Sciences, Department of Computer Sciences and

Engineering, Washington University, St. Louis, [email protected].

1

R Loui, J Norman, JAltepeter, D Pinkard, D Craven, J

Linsday, M Foltz, “Progress on Room 5: a testbed for

public interactive semi-formal legal argumentation”, 1997,

Proceedings of the 6th International

Conference on Artificial intelligence and Law,

pp.207-214.

2

S Toulmin, The Uses

of Argument (1958).

3

C Marshall, F G Halasz, R A Rogers, W C Janssen,

“Aquanet: A Hypertext Tool to Hold Your Knowledge in Place”,

1991, Proceedings of ACM Hypertext,

San Antonio, TX, 261-275.

4

C Chesñevar, A Maguitman, R Loui, “Logical

Models of Argument'” (2000) 32 (4) ACM

Computing Surveys, pp. 343-387.

5

N Rescher, Dialectics:

A Controversy-Oriented Approach to the Theory of Knowledge

(1977).

6

R Loui, J Norman, J Altepeter, D Pinkard, D Craven, J Linsday, M

Foltz, “Progress on Room 5: a testbed for public

interactive semi-formal legal argumentation”, 1997,

Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Artificial

intelligence and Law, pp.207-214.

7

K Ashley, Modeling

Legal Arguments: Reasoning with Cases and Hypotheticals

(1991).

8

J Raz, The Authority of Law

(1997).

9

R Loui, J Norman, “Eliding the arguments of

cases,” 1997, unpublished paper presented at the International

Association for Philosophy of Law and Social Philosophy (IVR),

Buenos Aires.

10

H Prakken, G Sartor, “Reasoning about

precedents in a dialogue game”, 1997, Proceedings

of the 6th

International Conference on Artificial intelligence and Law,

pp.1-9.

11

L K Branting, K Ashley, C Sunstein, “Legal

Reasoning & Artificial Intelligence: How Computers ‘Think’

Like Lawyers” (2001) 8 (1) University

of Chicago Law School Roundtable.

12

J Swift, A

Modest Proposal and Other Satirical Works

(1996)

BAILII:

Copyright Policy |

Disclaimers |

Privacy Policy |

Feedback |

Donate to BAILII

URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/other/journals/Script-ed/2008/5_1_SCRIPT-ed_176.html