Bibliography

Information technology changes at a breathless and bewildering

pace. Moore’s law is the classic benchmark for hardware improvement; but

when we consider the use as well as the industrial production of IT it becomes

apparent that there is more than one rate of change involved.

In her summary of the literature on how such change affects social institutions,

Marlene Scardamalia (2001, p 171) drew the useful comparison between four

different rates of change – technological innovation (very fast); the rate

of adoptions of technological innovations (fast, but depends on the product

– compare mp3 players with video conferencing, for instance); the rate at

which practices change as the result of new technologies (much slower – in

education, the ‘glass book’ is still depressingly common); and the rate at

which practices improve generally as a consequence of a technological innovation

(very slow – touch screens in commercial applications, for instance, or networked

learning ecologies in education).

These different rates of change are of course context-dependent,

on geography, wealth, social networks, and much else. In the midst of such

bewildering change, and faced with the hype of the virtual and the false lure

of context-free information networks and exchanges, how can we tell what is

peripheral in the field of legal education and ICT, and will perish soon,

and what will endure for more than the market lifetime of a silicon chip (Harnad

2001a; Harnad 2001b)? Which bits of IT, in both the technical and

ordinary sense of the word, are important to professional legal educators?

The question requires us to define at least two important issues. First,

who is involved in professional legal education? Second, social perceptions

of the role of professional legal education affect how ICT will be used within

it, and any analysis must take this into account. Bearing this in mind, what

do professional legal educators interpret as their practice or practices in

legal education, and where does ICT fit into this interpretation?

A brief glance at the life-cycle of a professional legal

education course will show there are fundamental differences in almost every

aspect between undergraduate and postgraduate professional legal education

programmes of study – in pre-student

attraction to the institution and its course, application interview, clearing

offer, new student arrival, registration, induction course teaching, communications,

library, computing, teachers and their backgrounds and experience, assignments,

assessments, results, appeals, resits, careers, welfare, administration, graduation,

and alumni activities. Where in general a liberal consensus regarding

content and method is pre-defined for undergraduates by academics, where the

boundaries of that consensus during a programme of study is defined in many

subtle ways, where content is assessed by academics and the whole process

is under academic control, the professional legal educator’s life is by comparison

less in his or her control regarding matters right across the course life-cycle

(the literature on this goes back at least to Twining (1967) – see also Hepple

(1996)). There are important regulatory issues and codes to which professional

programmes require to conform, and which affect the culture of a course.

Undergraduate courses, though they are under pressure from other directions,

are largely sheltered from such close-quarter regulatory concerns. To be

sure, there are quality assurance issues and procedures to be attended to,

but in the past few years, in Scotland at least, these have tended to be review

processes internal to the university, and not directly under the control of

external regulators.

For those involved in professional programmes, though, the

environment is more commercially competitive, is more exposed to market values

and neoliberalist values of accountability and enterprise. There are more

stakeholders: the profession, the regulatory bodies, the Bars, the universities

are but four principal players, and by no means the only ones. The identity

of professional legal teachers itself is multivarious, protean. They are

practitioner-tutors, or full-time staff with a practice background but a few

of them are academics with responsibility for professional legal education.

Some of them exist in-between, with both regulatory and academic research

obligations to fulfil.

The ground of their teaching practice has not been that of

the ‘high ground’ of academic practice, as Donald Schön has it, but is much

closer to the swamp of practice, where political and cultural pressures, particularly

those of policy and audit, affect them profoundly, in all the jurisdictions

of these isles. And by the phrase ‘policy and audit’ I refer particularly

to the analyses of it carried out by Marilyn Strathern (see for example Strathern

(2000a; 2000b; 2004) – more of this below). In Ireland they have been subject

to reports by the Competition Authority. In Northern Ireland there have been

similar attentions. In England and Wales the Training Framework Review has

recently put the whole system of professional legal education into doubt.

In Scotland the Diploma Working Party is reviewing the content and method

of the primary course in the professional education programme in Scotland,

and this will affect the entire three-year programme of professional education.

The depth and speed of the change within professional legal education, its

proximity to political pressures such as that brought about for example by

Clementi in England and Wales, means that professional legal educators are

under more pressure from this direction than their academic colleagues

As a result, professional legal education is permanently

on the edge. It exists on a fault-line that is constantly shifting, between

the academy and the profession, between education and training, between university

and external regulatory demands. Professional educators live and work in

border country where there are boundary disputes, jurisdictional claims, shifting

allegiances and the constant negotiation and re-negotiation of educational

claims and counter-claims; and their modes of working reflect this.

Or at least one assumes so. But while there is emerging

a body of research on the working lives and practices of legal academics,

there is little that examines the working lives of professional legal educators

(Brownsword 1999; Mytton, 2003; Cownie 2004). How do they resolve these remarkable

sets of pressures and conflicts in their everyday educational practice? If,

as Barnett says of academics, research performance is a crucial part of their

‘professional identity’, what then is the fulcrum of the identity of professional

legal educators, most of whom engage in little published research (Barnett

1990, p 135)? Above all what is their ‘living educational theory’?

The answers to these questions would in effect be a form

of raison d’être for professional legal

educators, where the être must be more of a phenomenological construct

than a mere raison d’employ. Remarkably, there is almost no discussion

of what might be regarded as meta-theory by which they explain their work

and lives to themselves and to others (statements of programme learning outcomes

are hardly a meta-theory). Meta-theory is a substantial project on its own,

and there is insufficient space to do it justice here; but towards the end

of the article I shall describe possible theoretical approaches which, I would

suggest, can at least begin to underpin the use of ICT in imaginative and

powerful ways within professional legal education.

That it is difficult to inhabit the demesne of ICT

is shown by the research literature into academic staff use of technology.

Coupal identified three stages of development in ICT use by teachers: ‘literacy

uses ( a technology-centred pedagogy); adaptive uses (a teacher-centred, direct

instruction pedagogy); and transforming uses (a student-centred, constructivist

pedagogy)’ (Coupal 2004, 591); and this has been observed by other researchers

(eg Bottino 2004). What do teachers feel about the use of ICT, though, and

how do they perceive its effects on their practice? Over a decade ago Klem

and Moran analysed why teachers had negative reactions to ICT (Klem &

Moran 1994). In their study, teachers viewed ICT as bringing about a loss

of power, control and authority within the traditional teaching environment.

Their view of technology was that, to misquote Christensen (2003), all

technology was disruptive; very little of it was seen as being sustaining

of traditional educational practices.

In one sense the introduction of ICT is a new twist to an

old thread of protest, where teachers perceive they are oppressed in one way

or another by varied forms of new educational practice. Dewey, for instance,

in an early version of protests against the New Managerialism, once declared:

“In the name of scientific administration

and close supervision, the initiative and freedom of the actual teacher are

more and more curtailed. By means of achievement and mental tests carried

on from the central office, of a steadily issuing stream of dictated typewritten

communications, of minute and explicit syllabi of instruction, the teacher

is reduced to a living phonograph. In the name of centralization of responsibility

and of efficiency and even science, everything possible is done to make the

teacher into a servile rubber stamp.” (Dewey 1991 [1927], pp 122-3)

Penteado (2001) came to the same conclusion as Klem and Moran,

but she postulated that such confrontation between old and new was inevitable,

and that as a result teachers using technology were forced to move from what

she called relative comfort zones into risk zones. As a consequence, and

at a deep level, teachers required to re-negotiate their educational practice

in order to use technology. Applying Penteado’s findings to law leads one

to realise that such re-negotiation is a constant process, depending on many

factors: stability of an area of law from one academic year to another, feelings

of certainty about course content, experience of teaching the course, experience

with some of the technology being used or none of it, the perceived riskiness

of the technology in use with students, and so on.

Some of these points were raised in the legal domain by Alldridge

& Mumford (1998), though they drew no distinction between academic and

professional stage use of ICT, possibly because in the late nineties neither

ICT applications nor specific use by students and staff involved in professional

legal education were sufficiently developed or widespread for the distinction

to be visible. What is interesting about Penteado’s findings is that it presents

us with an unsettling picture of constant change that would appear to be a

consequence of the speed of change implicit in Moore’s Law and summarised

by Scardamalia above.

But there are deeper issues here than personal negotiation

of IT processes. Too often our analyses of ICT in education exist at the

level of the instrumental and teleological. We need to consider the deeper

issues of what we do and why, and above all the context of how we use any

technology, whether it be computer, webcast, podcast, blog, interactive whiteboard,

photocopier, book, vellum, clay tablet, oral statement. In this respect the

analyses that Marilyn Strathern (2000) has made of the role of policy and

audit, and her critique of the concept of the ‘virtual society’ are helpful

to our present analysis. As she has observed, ‘ICT is a highly visible ally

of audit practices. Its speeding up of the performance of office equipment

does not just facilitate the production of the audit reports and so forth,

but as an entity in itself (as ICT or IT) can be used as an indicator

of performance.’ Audit, she suggests, elicits ‘a view of an institution or

organisation as a system – as a system, not as a “society”’; and she compares

the closed loop of such system analyses with the open-ended analyses of ethnographic

practices that treat organisations as social organisms, where disconnections,

loose ends, uncertainties and unpredictabilities are not to be tidied away

but studied for what they tell us about an organisation’s development and

culture.

Strathern’s observations are enacted by anthropologists of

workplace learning such as Lave and Wenger. As they remind us, most learning

we undertake in our lives does not consist of lectures and tutorials followed

by a two-hour unseen essay assessment in an examination hall. Instead, the

vast majority of our learning is situated in the world, and rises out of our

actions there. Lave and Wenger’s analysis of Liberian tailors is a classic

study of learning in the workplace, where they show how, over time, apprentices

are drawn closer into the centre of valued work practices, after demonstrating

their ability in peripheral activities (Lave & Wenger, 1991. See also

Billett 2001; Engerström, Engerström & Karkainnen 1995; Engerström 2001;

Evans, Hodkinson, Unwin 2002). Such activities are important to the developing

expertise of the apprentice tailors: they are in effect ways of legitimising

practice and progression within a community of practitioners – hence the title

of Lave and Wenger’s text, Legitimate Peripheral Participation. They

help to develop ‘shared participative memory’ (Wenger 1998, p 11). As Lave

& Wenger put it,

“Legitimate peripheral participation

provides a way to speak about the relations between newcomers and old-timers,

and about activities, identities, artefacts, and communities of knowledge

and practice. It concerns the process by which newcomers become part of a

community of practice.”(p 29)

As they point out, the slow accretion of learning within

the community alters identity as well as practice: indeed, changed identity

is the essence of apprenticeship, not merely for apprentices, but for anyone

learning new sets of skills, knowledge and values.

In many ways the literature on situated learning gives professional

educators a body of profound theory with which to view their own practice

as teachers, positioned between academia, regulators and practice. But it

also shows them an alternative future in the use of ICT in learning and teaching.

Technology need not be baffling, dangerous, fraught with anxiety, and a disempowering

experience for staff, as Klem & Moran and Penteado report it to be. It

can be a process of legitimate peripheral participation, of moving steadily

ever inwards, towards more and more complex use of technology in educational

design and implementation. Communities of practice and design, in the workplace

and beyond it, and learning from the literature, from our own practice and

that of others, are essential to this approach. For students are drawn to

professional practice, and if ICT is to be integrated successfully into professional

educational curricula, one useful way would be to adopt an ethnographic approach

to the professional use of IT; to examine how professional practice uses ICT,

and adopt versions of it adapted to professional courses

This presupposes, of course, a professional legal educational

research culture. The good news is that in terms of the use of ICT, legitimate

peripheral participation happens already – what we need to do is to recognise

it, build upon it, and construct support networks for ourselves. Most of

us are aware of the web, for example; and almost all of us use email. We

need to build on that and develop our experience with other forms of communications

applications. If we are unsure about using discussion forums with students,

why not use them amongst ourselves before we step into the risk zone? The

literature is full of guidelines on how to do this well, and there are plenty

of forums on the web where it is possible to lurk and read until you catch

the drift and tone, and contribute. If chat rooms or SMS, with their multi-pitch

audiences and fragmented conversations seem crazily fast and complex forms

of communication, why don’t we use them with each other, before we attempt

to use them in relation to legal education? For an inspirational example

of how students can use such media to good effect, see http://journals.aol.com/transmogriflaw/journey/entries/69.

We could also read the literature – see for example Walker (2004); Cox, Carr

& Hall (2004). Are we interested in simulation for legal learning? Find

out about simulation by joining any one of the many massively multi-user online

role-playing games on the web. At a cost of around 12 dollars a month, you

will have more fun and grief than you ever thought possible on the web. Do

you use personal digital assistants (PDAs)? Why not think about using them

for teaching with students? This has been done a number of times in various

areas of medical education, and there is little reason why we should not learn

about the local conditions of such implementations and attempt similar innovations

in our own discipline (Smørdal & Gregory 2003; and the special issue on

wireless and mobile technologies in education in Journal of Computer-assisted

Learning, 2005, 21, 3).

Above all, we need to build a community of practice where

we can discuss ideas, communicate and examine results, compare implementations,

and learn from each other. Such a community can help us to learn in a safe

environment before moving into the risk zone – as Lave and Wenger point out,

the reality of a task is significantly different when it is performed for

real rather than in simulated environments. The practice of extending safe

zones into zones of risk is a basic human activity. It defines us and identifies

us to others around us. We become who we are as a result of it and learning

becomes, quite profoundly, a part of us. If professional educators (institutions

as well as individuals) are to risk innovations and the unintended consequences

that the epigraphs quoted above caution about, then they need to start in

the safe zone, practise there; then move out of it into the riskier areas

of practice. The process requires an infrastructure that supports this movement.

It also requires ahead of us the challenges that we can move into from our

current positions. Staff development within communities of practice is a

key to this, and in particular helping staff to:

- Explore the fit between their personal theories of teaching

and learning, and those embedded in forms of innovative teaching

- Access resources that support them in learning to use

new technology

- Acknowledge and address their fears about teaching innovation

in a constructive way

- Access examples of good practice and successful implementations

Out of this can arise the material for research publication

-- state-of-the-art papers, meta-analytic research reviews, narrative reviews,

best-evidence syntheses, forum papers, methodological reviews, thematic reviews

and much else. In the next section I shall give an example of this happening

in one area of my own experience of ICT, namely the use of discussion forums.

In 1996 I ran a first version of a Personal Injury Negotiation

Project, with around 20 students, using MS Mail client, on Windows 3.1.1.

The project ran within a level 3 Clinical Legal Skills module on the BA Law

with Administrative Studies programme, Glasgow Caledonian University. Within

the project students responded to me and to each other by email, and project

instructions and the client matter were set out in paper-based confidential

instructions. Students were divided into ‘virtual firms’ of two or three

students. Half the firms acted for claimants, while the other half consisted

of solicitors for the insurers. In both technical and communicational terms

the system was crude, and because the network was prone to crashing it required

constant technical maintenance; but over the following three years it enabled

me to develop a basic repertoire of dialogic moves with students over email

(ie familiarity with the types of questions that students asked in

the project environment, and best ways to answer them – see figure 1 below).

It gave me confidence that I could deal with student questions on the broad

range of issues that I expected they would want information, namely:

1. procedural & substantive

issues relating to the transaction.

However I found that students asked other sorts of questions:

2. technical issues –

how to carry out particular procedures, for instance

3. ‘realia’ issues – how

real does the simulation become? Eg were the clients to be billed? The more

real the project became with each succeeding year, the more pressing and interesting

these questions became

4. interpersonal problems

that arose between firms negotiating with each other

5. interpersonal problems

that had arisen within firms, either interpersonal or workload-related (eg

freeloaders in a firm, or quality of work produced by one firm member being

perceived as below-par, and the like)

In addition students wanted to communicate confidentially

at times. They wanted to email each other, email other firms on the same

side of the negotiation, and email me as tutor. There was no equivalent of

a private chat facility in the single email channel that could accommodate

this. It became clear after the two years of running the project that the

complexity of the environment demanded more than a single point of information,

and that the informational structure of the environment would need to be re-planned.

My personal use of email had given me the confidence to embark on the project;

but the simulation project required not a univocal channel of communication,

but an architecture that was much more polyphonic and flexible in order to

accommodate the communicational requirements of the students as well as the

complex relationship between simulation and reality.

Figure 1: PI Negotiation Project 1997 – paper-based and

email-based information flows

On the basis of this experience, in 2000 for the first time

discussion forums were used on the project, which now ran within a quite different

institution and progamme of study, and with a student body of around 159 students. We set up separate forums for

the claimant firms and the defender firms, and began to address points 2-5

above. For point 2., students were given better training in the use of the

online environment, and thereafter queries were dealt with by the FAQ or as

a last resort, technical support. To deal with point 3, we used FAQs that

were reviewed each year on the basis of points raised by students during the

project. A year later, once the project had migrated from MS Outlook to a

fully web-based project, we dealt with point 4 by creating a ‘deal-room’ area

online for the students, whereby they could negotiate direct with each other.

Several solutions were adopted for point 5, none of them entirely satisfactory,

until we began to think seriously about the social and phenomenological nature

of the problem. This is described in detail elsewhere (Barton & Westwood

2005). The solution that worked best was to use tutors on the Diploma’s Practice

Management course as actual practice managers to the virtual firms.

In many ways this was a break-through for us. The tutors served as both mediatory

and disciplinary figures for the firms, as appropriate. We hoped that issues

under point 1. would channel to the forum. But the occasional students would

still email me privately. Where it was of little use to the others, I would

respond; but where an issue was useful to all, I did not reply to the person

privately, but asked permission to quote anonymously & comment on the

forum.

The forums have run every year since then to support student

learning. Now, the student year group of around 275 – a more than tenfold

increase in student numbers on the original project– is divided into virtual

firms. There are, therefore, two forums,

each passworded – one for the claimant group of firms, and one for the defender

firms. The postings are answered by myself and a practitioner, a Visiting

Professor to the GGSL, Charles Hennessy (Charlie). The discussion threads

tend to be brief: often a single posting, answered by Charlie or myself.

Sometimes students will follow up with a qualification or supplementary question,

but the conversation largely consists of ‘how-to’ questions and replies.

This suits the nature of the information that students need at this level

of their learning in the project. With no formal classes, apart from a voluntary

‘surgery’ held by Charlie, this is the only way for students to obtain expert

advice on this particular transaction (they can of course obtain general advice

on PI transactions from textbooks, but we want them to learn the specifics,

and learn from the specifics, of handling a transaction).

By any standards of natural, face-to-face conversation, the

postings are shallow, abrupt. There is rarely any extended conceptual discussion.

They mostly concern factual or procedural matters, with the occasional matters

of negotiation strategy being discussed. If one were to imagine the threads

as topics of conversation in a tutorial, they would be disjunctive and irritating

to listen to. But students are not listening to a conversation in real time:

they are reading a slowly evolving list of Q & As that is relevant to

the progress of their own transactional files; and for this reason, the discussion

forum succeeds as a method of disseminating ideas, guidelines and practice

that is directly relevant to the students’ own learning in the project.

The forums succeed, therefore, but they do so because they

fulfil a need on the course. There is a deliberate lack of face-to-face

classes: to get information and knowledge, students must enter their forum

to scan for answers to their questions, or post questions themselves. The

forums were designed to take this form: students will seek for information

by the quickest and most intuitive route – almost invariably, face-to-face

from tutors. The forums supply information that is, in one way, highly constrained;

but in other ways is highly flexible and adaptive, and addressed to large

numbers of students.

We can see this in operation if we briefly analyse below

a couple of forum postings.

In the first, Sarah is unsure how to form a strategy for obtaining medical

information. She sought an answer on the forum, and watching her question

were around 130 other students… This is her posting, headed ‘Medical Records’:

“We have been discussing the best

way to obtain medical evidence of the injury sustained by the claimant. Since

the accident resulted in a hospital visit, we feel that the records made by

the hospital and the GP at the time of the accident would be relevant. I

notice that there has been a lot of prior discussion in past years regarding

medical mandates although this seems a very detailed topic. Would it be competent

for the client to obtain copies of his medical records and simply pass them

onto our firm?”

From my point of view as a facilitator, this is an interesting

posting. Sarah has obviously thought about the issue before posting to the

forum. She has scanned the archived forum, and has a sense from them of how

she might proceed. She thinks she wants to see the records, but is not entirely

sure. She is also aware that obtaining mandates, writing to hospital administrators

and the like takes time and effort and understandably she wants to streamline

this process; but in a way that fits with practice. She has arrived at a

solution that seems to sever the Gordian knot of information dissemination

and retrieval at a stroke. But she is unsure if this is ‘competent’ on several

levels: can one communicate with the client in this way? And are students

allowed to do this on the PI project? Reading her posting, I was aware that

I would need to address all these issues.

My response was as follows:

“This is an interesting point,

Sarah. I'll deal with your ingenious solution first. It's doubtful whether

the client will be in a position (either from a medical or a legal point of

view) to pass on to you the information that you're seeking. He's also liable

to wonder why he's paying you to represent him when he has to visit medics,

come away with records, be told that these are not quite what you were

looking for, and asked to go back again for more.

If your firm were to ask for medical

records from hospital or doctor, the same general point about medical competence

would apply. Suppose that the hard-pressed admin staff in Ardcalloch Royal

send you sheaves of your client's medical records. Which are relevant to

the accident? And are you going to be able to interpret (or even decipher)

medical short-hand, scribbled notes, medical jargon, etc?

Best to request a medical report;

and for that report to be focused on specific points that you want clarified

as to the nature and extent of injury, and other related matters. And for

that, your doctor or consultant will need your client's mandate. Don't get

too involved in it: mandates can be more complicated, but they aren't in this

project. Just a simple two-liner will do. Your client will return it, signed,

and you can forward to whomever with a letter stating what you want."

My reply addresses the transactional issues, and the project

issues. Sarah is given advice as to the procedure to follow, and why practitioners

do it this way. She is also, in the last paragraph, given directions as to

how realistic the project is. In this respect the forum performs an interesting

function in the simulations that take place in Ardcalloch, our simulated virtual

town. It mediates between the wholly simulated world of Ardcalloch, the reality

of the Diploma, and the reality of personal injury transactional practice.

It is also an online space where students can step out of role in the simulation

and obtain advice on what they have done, or are about to do, before they

step back into the simulation again. If at first it seems shallow and superficial,

the space itself, mediating between three areas of information and knowledge,

actually performs a relatively sophisticated educational role.

As the personal injury claim develops throughout the course

of the project, the procedural issues become quite complex for the firms,

and involve ethical issues. Here is an example, this time from a firm acting

for the insurance company in the claim (Ardcalloch University is the employer

of the injured claimant), and answered by Charles Hennessy:

Charles’ answer:

“Good question.

No, you have no duty to report the accident to the HSE if the client hasn’t

done so.

You could always write and advise

the client that they should have (why do you think they should have ? -

don’t rely on their website, look at the legislation and let me know the legal

basis for the obligation to report an accident like this) - Assume the client

says "Fine, thanks for your advice but we are not doing it. What will

happen to us if they find out - which they probably won’t?" What advice

would you give then?”

Charlie’s posting answers the initial problem, but raises

several issues arising from the student’s question, and which arise from the

situation that the student has described. In other words, he is extending

the range of the simulation into hypotheticals, modelling practical legal

thinking for students, mapping out possible ethical issues that arise not

from problems hidden in the scenario (teacher-based interventions…), but from

the students’ own queries and approaches.

Both discussion forums follow general guidelines as to good

practice, without making this too overt. We have a list of protocols for

students, but unseen protocols were there too, and guided student participation.

We encouraged students to participate, but if they did not, we assumed they

were content with the information on the forum or had consulted previous forums,

or had found the information they needed elsewhere, for example in practitioner

journals or texts. We were content if the majority of students ‘lurked’ on

the forum. Amongst a number of summaries of this aspect of the literature,

one could take Klemm’s synopsis, and compare it with our own practice (Klemm

2002; Table 1 below).

Table 1

|

|

Klemm’s anti-lurking protocols

|

Our practice

|

|

1.

|

Require participation – don’t let it be optional

|

Lurking was OK for us – the forums, after all, were

resources for students. And if students had no questions, and no useful

comments, we were happy for them to learn from others.

|

|

2.

|

Form learning teams

|

Our virtual firms were just that

|

|

3.

|

Make the activity interesting

|

Feedback from students told us the transaction was

interesting and highly relevant

|

|

4.

|

Don’t settle for opinions only

|

Students asked precise questions and were given precise

answers

|

|

5.

|

Structure the activity

|

Better still – students structured their own activity,

based on our guidance (and the forum contributed to that set of guidance)

|

|

6.

|

Require a ‘hand-in assignment’ (deliverable)

|

Students required to achieve the negotiated settlement

that was the end-point of the transaction.

|

|

7.

|

Know what you are looking for and involve yourself

to make it happen

|

Students are clear about the aims of the forum, and

both Charlie and I answered postings on it.

|

|

8.

|

Peer grading

|

We did not use this nor do we consider it useful, given

our students’ inexperience in PI transactions. However next year we

shall introduce peer grading of perceived effort.

|

In addition to facilitating the claimant and defender

discussion forums, I also answered with Charlie on a project facilitators’

discussion forum. This was used as a means for the seven postgraduate facilitators

to contact Charlie and me and each other during the project if any problems

arose regarding the correspondence they were sending to students in the guise

of fictitious characters in Ardcalloch, or if they wanted advice on proper

procedure.

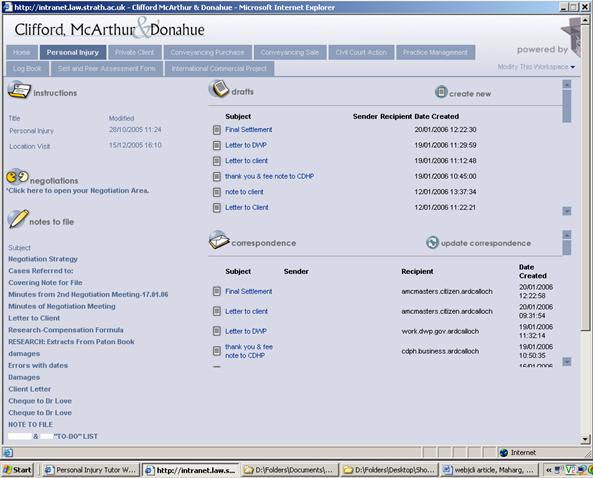

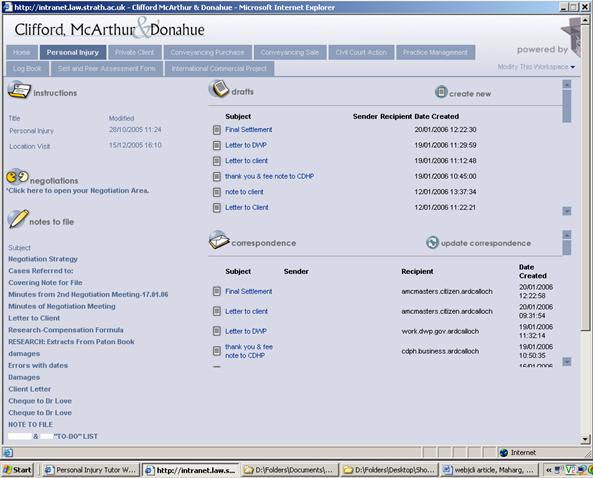

The following diagram (Figure 2) illustrates the structural

relationships between the communication flows in the project as of 2004 and

subsequent years to the present; while Figure 3 gives a sense of the workspace

within which students completed the transactional tasks.

Figure 2: PI Negotiation Project, 2004 – web-based

information flows. Note the three forms of discussion forum used in the

project, represented in bold.

Figure 3: sample student intranet page, Personal Injury

transactional workspace (names removed for anonymity)

The transactional work undertaken by students was therefore

sustained by at least three different dialogue communities, which had different

and sometimes overlapping audiences, each of whom brought different questions

and bodies of knowledge to the discussions. The discussions exemplify rhetorical

guidelines regarding audience, purpose, channels and media (Flower 1994).

Above all, they are appropriate to the audience needs, and they are so because

they both help to create and sustain different communities of practice

within the project. Throughout there is conversation – nearly always student-initiated

– which is essential for student learning on the project – a permanent conversation

in pixels and bits that leaves a trace and perishes only if erased – verba

volent, scripta manent (Harnad, 2001b)

The concept of verba as scripta can lead us

to think of discussion forums as awkward, clumsy affairs – not a real conversation,

after all, and surely not as effective as a tutorial on a Personal Injury

topic. But we would argue that a discussion forum is simply different from

a tutorial, neither better nor worse as a medium for learning. Where tutorials

and discussion forums overlap is that designing, structuring and facilitating

discussion forums is an art, an educational skill similar to good tutoring,

or to lecturing or writing educational resources, but separate, and worthy

of special staff development support in the move from safe to risk zones.

And as with most arts, sometimes the most unlikely ideas are actually the

most productive. At first glance the use of chat-room technology might have

no place to play in face-to-face meetings, for instance. But in an experiment

reported by Clay Shirky, the software was used to match and enhance the communicative

complexity of certain types of face-to-face meetings -- for example, notes

to self (a kind of public ‘thinking out loud’); high-quality text annotation,

and \whisper commands (by which one could ‘whisper’ to anyone in the room

– Shirky (2002))

As Gilly Salmon (2000) has shown, students often require

to feel confident in their use of a VLE before they can begin to dialogue.

The dialogue space, too, needs to be a safe one before students will

move from the relatively safe evanescence of verba to committing themselves

to more permanent scripta. Salmon’s concept of ‘e-tivities’ can help

create such a space (2000b – see also Pavey & Garland 2004). The concept

needs to be treated as highly flexible, depending on the audience, but it

is, nevertheless, a valuable acknowledgement of the social nature of

online dialogue. As Bourdieu and others have pointed out, there are no such

things as neutral spaces in education (Lefebvre 1991; Bourdieu 1989). Crook

& Light (2002, p 156) made the same point as regards virtual space: for

them, online discussion cannot be ‘decoupled from the artefacts, technologies,

symbol systems, institutional structures, and other cultural paraphernalia

within which it is constituted’. In this, as in much else regarding technology,

we need to separate the peripheral from the essential. And as Harnad and

many others have pointed out, the permanent bits are the communicative essentials

– those trace elements of communication on the web that are evidence of knowledge,

dialogue and learning.

But do the forums help students to learn, or are they

just talk for talk’s sake (McKellar & Maharg 2004)? The simple fact that

students communicate using them is crude evidence: students can, after all,

communicate with each other in much more intuitive and cool ways – mobiles,

SMS, IM, etc. The research of Howell-Richardson & Mellar (1996) indicates

that much learning can take place, but that even small modifications to the

structure of an online learning environment or task can affect communication

outcomes considerably. We need to have a way of analysing and graphically

representing such learning for our purposes as teachers. One way of doing

this in the near future will be by computer-generated content analysis. It

is possible, using neural net technology, to generate methods for autonomically

categorising postings into cognitive categories. Already such systems are

generating strong reliability findings (McKlin et al 2002).

Just as the physical space of learning contributes to student

learning, so the construction of the forum can enhance or inhibit learning

(Becker & Steele 1995). The literature on situated learning emphasises

the effect of physical and social contexts on learning. According to this

research, learning is more likely to be deep and effective when situated in

discipline-specific and authentic tasks (Brown (2000), Brown, Collins &

Duguid, (1989) Barab, Hay & Duffy (1998); Herrington, Oliver & Reeves

(2002)). But the construction of tasks and dialogue in such spaces requires

effort, skill, reflection, practice. Above all, it requires an awareness

of the different forms of dialogue that can contribute to an educational experience.

There are times when tutors are best to intervene, but there are occasions

when it is best for a tutor to remain silent (Rohfeld & Hiemstra 1995;

Hughes & Daykin 2002). Tutors need to think carefully about the forms

of questions they ask online, which can inhibit discussion, or stimulate it

(Muilenberg & Berge 2002). Tutors also need to think about the ways in

which postings represent different forms of group interactions, based upon

how individuals interact with each other, and how ‘roles and strategies emerge

amongst the participants’, which in turn can lead to ‘deeper insights into

how professionals collaborate to develop their own practice, and into the

complexity of the interactions between individual and group processes during

these collaborations’ (De Laat & Lally (2004), p 171; Klemm (2004); Prammanee

(2003)). Such collaborations, between students, between students and staff,

and between staff, can only occur within relatively safe zones.

This held true for the developmental process as well. The

snapshot comparisons that are represented by Figures 1 and 2 will show the

difference in polyvocality, and in informational flows between the two iterations

of the project. It was certainly the case for me that the complexity of the

architecture as it now exists could not have been generated in the first couple

of years of the project’s development. Quite simply, the tools to create

the project ‘middleware’ did not exist in 1996; but more importantly, none

of us then had the confidence that such a complex environment would work for

students, for staff, or indeed how the environment could be maintained from

one year to the next. It required the slow accretion of experience, and the

development of a local community of practice within the GGSL to create sophisticated

tools for learning (the acknowledgements at endnote four make this quite clear).

But our own community was also a tiny fragment of a much vaster community

of interests stretching globally and historically across the web: the emerging

practice in legal education and ICT; the literature on constructivism, on

web-based instruction and design; the form of newsgroup communities of the

web, the early communities grouping around MUDs and MOOs, educational experiments

in online communities and suchlike.

I have given a detailed example of communities of practice

in action in professional legal education, and a brief description of one

of the applications used in that arena. Such examples, of course, can be

appropriated by any sector of higher education, and by any discipline. But

is there a body of meta-theory that can guide our practice as professional

legal educators, and which can help us to come to terms with new technologies

such as described above? I would argue that there is, and that it arises

not just from educational practice, or from contemporary research on web-based

learning and teaching (important though that is); but also – following Strathern

– from the very uncertainties and marginal position of the teaching practices

of professional educators. I shall set this out in greater detail elsewhere,

but for now let me sketch out the position very briefly.

The nature of our teaching is close to practice, much closer

than for many academics. We can adapt forms of theory that grow in part from

the dialogue of the academy with practice, and of these, there are none so

apt as pragmatism, and that form of pragmatism associated with American realism.

I do not refer primarily to the form of neo-pragmatism that enjoyed a brief

popularity during the eighties and early nineties, but the pragmatic realism

of John Dewey, Karl Llewellyn, and others within and beyond the Metaphysical

Club (Menand 2002). What might be the relevance of this theory for us today?

We can illustrate it by taking an interesting episode that

involved Dewey in the early twenties, when he was at Columbia University.

Soon after his arrival at Columbia, Dewey became involved in collaboration

with a number of different departments. In the summer of 1922 he was invited

by Harlan Fisk Stone, dean of the School of Law at Columbia, to give a course

on Logical and Ethical Problems of Law. This course may have been one of

a number of experimental courses held in the session 1922-3, and organised

by Herman Oliphant. The course outline and materials have survived in manuscript

form amongst Stone’s papers in the Butler Library at Columbia, and it is clear

that the materials produced for this course were later used as an essay, 'Logical

Method and Law' (Dewey 1983) In this essay, Dewey is concerned to define

the form of logical enquiry used by law. In doing so, he notes the 'apparent

disparity which exists between actual legal development and the strict requirements

of logical theory' (p 68); and quotes one of Holmes' famous apothegms - '"The

actual life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience"' (p

69). Dewey agrees with Holmes, but only in so far as one defines logic as

strict syllogism. As he points out, 'No lawyer ever thought out the case

of a client in terms of the syllogism. He begins with a conclusion which

he intends to reach, favourable to his client of course, and then analyzes

the facts of the situation to find material out of which to construct a favourable

statement of facts, to form a minor premiss.' (p 72). Dewey emphasises

in this form of logic 'principles of interpretation' over against rigid rules,

and the role of general rules as working hypotheses, needing to be constantly

tested by the way in which they work out in application to concrete situations

(pp 75-6). He defined this logic as 'relative to consequences rather than

to antecedents' (p 75, his italics). For Dewey, this 'infiltration into

law of a more experimental and flexible logic [was] a social as well as an

intellectual need' (p 77). While acknowledging that rules of law should be

as definite as possible, Dewey points out that the regularity of decision

springs not only from the rules themselves but from uniform and relatively

static social conditions. However, where 'new devices in business and communication

bring about new forms of human relationship' (p 74), then the power of 'antecedent

assurance' (p 74) is diminished.

In this brief essay we have a pre-eminent example of the

effect that sociologists and philosophers had upon the American legal realists

(for discussion, see Twining (1973); Hunt (1978); Duxbury, (1997)). Dewey's

language is pragmatist - the emphasis upon new forms of enquiry, the language

of progressive, evolutionary reform, the social ameliorism and underlying

optimism; an insistence upon the uncertainty of legal rules and their artificiality;

the dwelling upon experimentalism and instrumentalism. Realist views of legal

process (eg Frank’s famous statement that 'law may vary with the personality

of the judge who happens to pass upon any given case' – White 1978, p 123)

accord with pragmatist views on educational theory (see Dewey (1948, p 189)

where he attacks the generalist tendencies of individualistic, socialist and

organic social philosophies). In his general definition of pragmatism, Dewey

put this well:

“Pragmatism … does not insist

upon antecedent phenomena but upon consequent phenomena; not upon precedents

but upon the possibilities of action. And this change in point of view is

almost revolutionary in its consequences. An empiricism which is content

with repeating facts already past has no place for possibility and for liberty.”

(Dewey, J. (1989), p 33)

In statements such as these we can see many aspects of the

anti-formalism of the legal realists, not least a version of what Llewellyn

was to call ‘situation sense’ (Llewellyn (1960); Twining (1973), p 216).

As Dewey put it in a later essay, 'law is through and through a social phenomenon;

social in origin, in purpose or end', and he later defined law as an 'inter-activity

... [which] can be discussed only in terms of the social conditions in which

it arises and of what it concretely does there'.

I would hold that everything in the last paragraph holds

powerfully for those of us involved today in professional legal education,

and no more so than in the forms of teaching that we use with technology.

New devices in business and communication have indeed brought about new forms

of relations within the world of business and the law, and they can be adapted

and used to transform our own teaching and learning. To do that, we need

to carry out empirical field work to determine how legal professionals work

with IT – visit firms, talk with IT service providers to law firms, with fee-earners

using software applications, visit legal IT conferences, discuss amongst ourselves

how we might better prepare our students for the use of ICT in legal practice,

think critically about the role and effect that IT has upon the legal profession.

But is that all? Is professional legal education simply

to be a mimesis of legal practice? Is this the limit of our educative

ambitions, given what Dewey says about the place of possibility and liberty

in education? If it is, then we risk repeating the failure of the realist

enterprise. For most historians of the movement, the realist projects of

the early twentieth century were unsuccessful – even realists themselves acknowledged

that the integration of social science methodology was partial and limited

at best (Duxbury (1995), p 130, quoting Llewellyn & Hoebel (1941), p 41).

Much of it ultimately transmogrified into pretexts of rationalised instrumentalism.

In legal educational theory, while reacting vigorously against the Langdellian

orthodoxy realists failed, for whatever reasons, ‘to devise a convincing alternative

framework of their own’ (Duxbury (1995), p 158). It is deeply ironic that

Dewey’s own radical educational approaches could have given the realists the

conceptual tools with which to transform their own educational practices –

tools which were left largely unused.

I would argue that as educators, we need to avoid the evasion

of the realists (as Cornell West termed it – West (1989)) while using the

tools that stem from the pragmatist tradition. There are many ways we can

represent our educational practice to ourselves, discuss it, research it,

and seek to change it. Nowadays, there are many developments of educational

theory and practice, stemming from theorists and practitioners such as Dewey,

who have in many ways successfully transformed the educational fields in other

disciplines. We can thus begin to construct for ourselves and our discipline

a pragmatic approach. For example, it might be no bad thing that we listen

to Elliott Eisner’s concept of connoisseurship, where educators become connoisseurs

of learning experiences, and critics of that experience (Eisner 1998). Or

we could listen to what the theorists of transformative education have to

offer us.

Transformation of experience is the key idea here.

For if professional education can be both pragmatist and realist, this is

not all that it can be. Pragmatism has had a bad lay press for being primarily

a description of a fairly cynical way of being in the world, and an accepting

of social power structures. I hope I have said enough about it in remarks

above to indicate that this is not my reading of it. Nevertheless it could

be said that our practice as professional educators should not simply rest

with a realist view of practice and legal education. I would make a plea

that we take on board a transformative view of professional legal education.

I would hold that professional legal educators have a duty to transform professional

legal education – we are, after all, deeply concerned with what it is to be

a professional in the world, and in communicating that vision of professionality

to our students. Our definition of professionalism cannot be defined by the

ethical code of a profession alone: it must be defined in more committed moral

terms. We often talk of teaching professionalism in terms of thinking like

a lawyer, or dealing with uncertainty, or domesticating doubt, or routinising

transactions. But professionalism must have deeper moral foundations than

these. It must be redefined, and we must be part of the movement to transform

professionalism, that of our students and our own as teachers, the transformation

of which must otherwise lie with political bodies, market forces and other

forces within society which care much less than we do about our profession.

There is already a substantial literature on the subject in other disciplines.

On the subject of teaching professionalism in the medical fields, for instance,

the work of David Stern (2005) is useful, as is that of Cruess & Cruess

(1997a & b).

What might such transformative learning actually involve?

It could include the following:

- Making apparent to students the ‘invisible framework’

of the legal profession

- Analysing practice, and helping students to develop their

own reflective practice within the profession, while learning that practice,

and being aware of wider societal, cultural and business contexts.

- Acknowledging and then working to change the borders of

professional practice

- Transformative growth in professionalism (Taylor

(2002; 2004).

These points refer to ourselves as much as to our students.

Transformative growth for us ought to mean engaging with relevant educational

theory (the interdisciplinary literature on professionalism, for instance),

dialoguing with each other, with the profession, with regulators, and with

many others. In the medical educational field, for example, Eggly, Brennan

& Wiese-Rometsch (2005, p.375) recommend in their conclusions that ‘future

proposals of ideal professional behavior be revised periodically

to reflect current experiences of practicing physicians, trainees,

other health care providers and patients. Greater educational emphasis

should be placed on the systems and sociopolitical environment

in which trainees practice’.

In many respects transformative learning might be regarded

as a deeper form of pragmatic inquiry. Henderson & Kesson’s (2004) ‘seven

modes of inquiry’ are a useful summary of the breadth and reach of this educational

approach. For them a teacher’s pragmatic wisdom stems from enacting all seven

modes of inquiry: techne (craft reflection), poesis (attunement

to the creative process), praxis (critical inquiry), dialogos

(multiperspectival inquiry), phronesis (practical, deliberative wisdom),

polis (public moral inquiry), theoria (contemplative wisdom).

One might compare this with Schubert’s earlier research into typologies of

curriculum images that educators hold, which range from conservative images

such as curriculum as subject matter or discrete tasks to more

radical images of curriculum as experience and curriculum as currere

(or autobiographical reconceptualisation – Schubert (1985); Taylor

(2002), p 10.

Indeed, given the tension, uncertainty and constant shifting

of the field within which we professional legal educationalists work, I would

hold that these concepts are even more important to those of us working in

the field of professional education: they are the essence of our practice,

they are what enable us to survive in our educational landscape, and contribute

to the developing debate on professionalism and other concepts central to

our practice. It is an approach that Dewey would have heartily approved of.

I hope I’ve shown that the domain of ICT is a sophisticated

and fertile field for those of us involved in professional legal learning.

What we need to ensure is that we move from safe to risk zones at our own

pace, that our goals for ICT use are specific, measurable, and realistic,

and that we create our communities of research, practice and interest. Above

all, communication between everyone involved in design and implementation

is essential, as research has shown (Dale, Robertson & Shortis (2004);

European Commission (n.d.) (2002-06)). The example of ICT, though, has deeper

resonances. As with all innovations, it throws into relief our everyday practices,

and can make us question what we do, and why we do it. In the process, it

shows the need for us to examine our practice in the context of larger theoretical

concerns, both legal and educational; and above all the need for meta-theory

arising from our professional legal educational practice.

With the permission of the editors, this paper has been posted

on my blog at http://zeugma.typepad.com (under ‘Publications’),

and I invite readers to join the discussion of the paper in the blog. If you

wish to comment, go to the permalink at http://zeugma.typepad.com/zeugma/2006/06/web_journal_of_.html.

I look forward to discussing it with you.

ActionResearch.net, at http://www.bath.ac.uk/~edsajw/

Alldridge, P, Mumford, A (1998) ‘Gazing into the Future through

a VDU: Communications, Information Technology, and Law Teaching’ in Transformative

Visions of Legal Education, Bradney, A, Cownie, F (eds) (Oxford: Blackwell),

116-133

Barab, S A, Hay, K E, Duffy, T M, (1998) ‘Grounded Constructions

and How Technology Can Help’, TECHTRENDS, March, 15-23

Becker, F, Steele F (1995) Workplace by Design: Mapping

The High Performance Workspace, (San Francisco, Jossey-Bass)

Barnett, R (1990) The Idea of Higher Education, (Buckingham:

Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press)

Barton, K, Westwood, F (2005) ‘Collaborative Working Environments

in Professional Learning’, Practice, Profession, Ethics section, Society

of Legal Scholars Conference, Glasgow: University of Strathclyde

Billett, S (2001) Learning in the Workplace: Strategies

for Effective Practice, (New South Wales: Crow’s Nest)

Bottino, R.M. (2004). ‘The Evolution of ICT-based Learning

Environments: Which Perspectives for the School of the Future? British

Journal of Educational Technology, 35, 5, 553-567

Bourdieu, P (1989) ‘Social Space and Symbolic Power’, Sociological

Theory 7, 1, 14-25.

Brown, J S, Collins, A, Duguid, P (1989) ‘Situational Cognition

and the Culture of Learning’, Educational Researcher, 18, 1, 32-42

Brown, J S (2000) ‘Growing Up Digital: How the Web Changes

Work, Education, and the Ways People Learn’, Change, March/April, 11-20

Brownsword, R (1999) ‘Law schools for Lawyers, Citizens and

People’. In Cownie, F. (ed), The Law School: Global Issues, Local Questions

(Aldershot: Ashgate)

Cownie, F (2004) Legal Academics. Culture and Identities,

(Oxford: Hart Publishing)

Crook, C, Light, P (2002) ‘Virtual Society and the Cultural

Practice of Study’, in Woolgar, S., ed., Virtual Society? Technology,

Cyperbole, Reality, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 153-75

Commentary: Medicine and Professionalism, Archives of

Internal Medicine, 2003;163:145-149 at http://teacherweb.com/NY/StBarnabas/Professionalism/HTMLPage3.stm#REF-ICM20044-11

Cox, G, Carr, T, Hall, M. (2004) ‘Evaluating the Use of Synchronous

Communication in Two Blended Courses’, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning,

20, 3, 183-193

Coupal, L.V. (2004). ‘Constructivist Learning Theory and

Human Capital Theory:

Shifting Political and Educational Frameworks for Teachers’

ICT Professional

Development. British Journal of Educational Technology,

35, 5, 587-596.

Christensen, C M (2003) The Innovator’s Dilemma, (New

York: HarperBusiness)

Cruess, S.R., Cruess, R.L. (1997a) Professionalism Must Be

Taught, British Medical Journal, 1997;315:1674-1677

Cruess, R.L., Cruess, S.R. (1997b) Teaching Medicine as a

Profession in the Service of Healing”, Academic Medicine, 72, 11, 941-52

Dale, R, Robertson, S, Shortis, T (2004) ‘”You Can’t Not

Go with the Technological Flow, Can You?” Constructing ‘ICT’ and “teaching

and learning”’, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 20, 456-70

Dewey, J (1933) How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation

of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process, (Boston: D.C. Heath)

Dewey, J (1948) Reconstruction in Philosophy. (Boston:

Beacon Press)

Dewey, J (1983) ‘Logical Method and the Law’ in John

Dewey: The Middle Works, 1899-1924, vol 15: 1923-24, ed by Jo Ann Boydston,

textual editor Anne Sharpe. (Carbondale & Edwardsville: Southern Illinois

UP), 65-77

Dewey, J. (1989) ‘The Development of American Pragmatism’

in Pragmatism: The Classic Writings, Thayer, H S, ed, (Indianapolis,

Indiana: Hackett). First published 1931

Dewey, J (1991) ‘What is the Matter with Teaching?’, in John

Dewey: The Later Works, 1925-1953, vol 2: 1925-1927, ed by Boydston, J.A.,

(Carbondale & Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press), 116-123.

Duxbury, N. (1997) Patterns of American Jurisprudence,

(New York: Oxford University Press)

Eggly, S, Brennan, S, Wiese-Rometsch, W (2005) ‘Once When

I was On Call…,’ Theory versus Reality in Training for Professionalism’, Academic

Medicine, 80, 371-75

Eisner, E W (1998). The Enlightened Eye: Qualitative Inquiry

and the Enhancement of Educational Practice, (Upper Saddle River, NJ:

Merrill)

Engerström, Y (2001) ‘Expansive Learning at Work: Towards

an Activity-Theoretical Reconceptualisation’, Journal of Education and

Work, 14, 1, 133-56

Engerström, Y, Engerström, R, Karkainnen, M (1995) ‘Polycontextuality

and Boundary Crossing in Expert Cognition: Learning and Problem Solving in

Complex Work Activities’, Learning and Instruction, 5, 319-36

European Commission (n.d.) Technology Enhanced Learning

(2002-2006 Framework for Research in Technology Enhanced Learning of the

Information Societies Technologies [IST] Programme of the European Community),

(Brussels: European Commission)

Evans, K, Hodkinson, P, Unwin, L (2002) Working to Learn:

Transforming Learning in the Workplace, eds, (London: Kogan Page)

Flower, L. (1994). The Construction of Negotiated Meaning.

A Social Cognitive Theory of Writing, (Carbondale, IL: University of Southern

Illinois Press)

Garrison, D R, Anderson, T, Archer, W (2000) ‘Critical Inquiry

in a Text-based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education’ in

The Internet and Higher Education, 2, 2-3, 87-105

Garrison, D R, Anderson, T, Archer, W (2001) ‘Critical Thinking,

Cognitive Presence, and Computer Conferencing in Distance Education’ in American

Journal of Distance Education, 15, 1, 7-23

Haigh, N (1998) ‘Staff Development: An Enabling Role’, in

Latchem, C., Lockwood, F., eds, Staff Development in Open and Flexible

Learning, (London: Routledge), 182-192

Harnad, S (2001a) ‘Re: The “Library of Alexandria” Non-Problem’,

posting at http://www.ecs.soton.ac.uk/~harnad/Hypermail/Amsci/1780.html

Harnad, S (2001b) ‘Lecture et Ecriture Scientifique “Dans

le Ciel”: Une Anomalie Post-gutenbergienne et Comment la Résoudre’,

Text-e at http://www.text-e.org/debats/index.cfm?conftext_ID=7

Henderson, J G, Kesson, K R (2004) Curriculum Wisdom:

Educational Decisions in Democratic Societies, (New Jersey: Pearson

Henri, F (1992) ‘Computer Conferencing and Content Analysis’,

in Collaborative Learning Through Computer Conferencing: The Najaden Papers,

115-136, Kaye, A R, ed, (New York: Springer)

Hepple, B (1996) ‘The Renewal of the Liberal Law Degree’,

Cambridge Law Journal, 470-87

Herrington, J, Oliver, R, Reeves, T C (2002), ‘Patterns of

Engagement in Authentic Online Learning Environments’, ASCILITE Conference,

Auckland, NZ, http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/auckland02/proceedings/papers/085.pdf

Holsti, O (1969) Content Analysis for the Social Sciences

and Humanities. (Don Mills, ON: Addison-Wesley)

Howell-Richardson, C, and Mellar, H (1996) ‘A Methodology

for the Analysis of Patterns of Participation within Computer Mediated Communication

Courses, Instructional Science, 24, 47-69

Hughes, M and Daykin, N (2002) ‘Towards Constructivism: Investigating

Students’ Perceptions and Learning as a Result of Using an Online Environment’,

Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 39, 217-24

Hunt, A (1978) The Sociological Movement in Law, (London:

Macmillan)

Klem, E, Moran, C (1994) ‘”Whose Machines Are These?” Politics,

Power and the New Technology’, in Sullivan, P., Qualley, D. (eds) Pedagogy

in the Age of Politics, (Urbana, Illinois: National Council of Teachers

of English), 73-87

Klemm, W R (2002) ‘Eight Ways to Get Students More Engaged

in On-line Conferences’, The Higher Education Journal, 26, 1, 62-64

De Laat, M, Lally, V (2004) ‘It’s Not So Easy: Researching

the Complexity of Emergent Participant Roles and Awareness in Asynchronous

Networked Learning Discussions’, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning,

20, 165-71

Lave, J, Wenger, E (1991) Situated Learning: Legitimate

Peripheral Participation, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Lefebvre, H (1991) The Production of Space, (Oxford:

Blackwell)

Llewellyn, K (1960), The Common Law Tradition - Deciding

Appeals. Boston: (Toronto: Little, Brown)

Llewellyn, K, Hoebel, E A (1941) The Cheyenne Way: Conflict

and Case Law in Primitive Jurisprudence, (Norma: University of Oklahoma

Press)

McKellar, P, Maharg, P (2004) ‘Talk about Talk: Are Discussion

Forums Worth the Effort? Vocational Teachers’ Forum, UK Centre for Legal

Education, 2004, http://www.ukcle.ac.uk/vtf/maharg.html

McKlin, T, Harmon, S W, Evans, W, Jones, M G (2002) ‘Cognitive

Presence in Web-based Learning: A Content Analysis of Students’ Online Discussions’,

in ITFORUM listserv, http://it.coe.uga.edu/itforum/paper60/paper60.htm

Maharg, P, Paliwala, A (2002) ‘Negotiating the Learning Process

with Electronic Resources’, in Effective Learning and Teaching in Law,

Burridge, R., et al. eds (London: Kogan Page and ILT), 81-104

Maharg, P (2004a) ‘Virtual Firms: Transactional Learning

on the Web’, Journal of the Law Society Online at http://www.journalonline.co.uk/article.aspx?id=1001154.

Maharg, P (2004b) ‘Virtual Communities on the Web: Transactional

Learning and Teaching’, in Aan het werk met ICT in het academisch onderwijs,

Vedder, A. ed, (Nijmegen: Wolf Legal Publishers)

Menand, L (2002) The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas

in America, (New York: Flamingo

Moore, G. (1965) ‘Cramming more components onto integrated

circuits’, Electronics, 38, 8, ftp://download.intel.com/research/silicon/moorespaper.pdf

Muilenberg, L, Berge, Z L (2002) A Framework for Designing

Questions for Online Learning, http://www.emoderators.com/moderators/muilenburg.html

Mytton, E (2003) Lived Experiences of the Law Teacher The

Law Teacher 36

Pavey, J, Garland, S W (2004) ‘The Integration and Implementation

of “E-tivities” to Enhance Students’ Interaction and Learning’, Innovations

in Education and Teaching International, 41, 3, 305-16

Penteado, M (2001) ‘Computer-based Learning Environments:

Risks and Uncertainties for Teachers’, Ways of Knowing Journal, 1,

2, 22-33

Prammanee, N (2003) ‘Understanding Participation in Online

Courses: A Case Study of Perceptions of Online Interaction’, ITFORUM listserv,

http://it.coe.uga.edu/itforum/paper68/paper68.html.

Rheingold, H (1992) ‘A Slice of My Life in My Virtual Community’

http://interact.uoregon.edu/medialit/MLR/home/index.html

Riffe, D, Lacy, S, and Fico, F G (1998) Analyzing Media

Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, (Mawah, New

Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum)

Rohfeld, R W, Hiemstra, R (1995) ‘Moderating Discussions

in the Electronic Classroom’ in Computer-Mediated Communication and the

Online Classroom in Distance Education, Berge, Z L, Collins, M P , eds,

(Creskill, NJ: Hampton Press)

Salmon, G (2000a) E-moderating: The Key to Teaching and

Learning Online, (London: Kogan Page)

Salmon, G (2000b) E-tivities: The Key to Active Online

Learning, (London: Kogan Page)

Scardamalia, M (2001) ‘Big Change Questions: Will Educational

Institutions, within their Present Structures, be Able to Adapt Sufficiently

to Meet the Needs of the Information Age?’ The Journal of Educational Change,

2, 2, 171-176

Schubert, W H (1985) Curriculum: Perspective, Paradigm,

and Possibility, (New York: Prentice Hall)

Shirky, C., (2002) ‘In-room Chat as a Social Tool’, at http://www.openp2p.com/pub/a/p2p/2002/12/26/inroom_chat.html

Smørdal, O, Gregory, J (2003) ‘Personal Digital Assistants

in Medical Education and Practice’, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning,

19, 320-29

Stern, D (2005) Measuring Medical Professionalism,

(Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Strathern, M (2000a) ‘Virtual Society? Get Real! Abstraction

and Decontextualisation: An Anthropological Comment or: E for Ethnography’,

http://virtualsociety.sbs.ox.ac.uk/GRpapers/strathern.htm

Strathern, M (2000b) Audit Cultures.

Anthropological studies in Accountability, Ethics and the Academy,

EASA series in Social Anthropology, (London: Routledge)

Strathern, M (2004) Commons

and Borderlands: Working Papers on Interdisciplinarity, Accountability and

the Flow of Knowledge, (Wantage: Sean Kingston Publishing)

Taylor, P C, Gilmer, P J, Tobin, K (2002) Transforming

Undergraduate Science Teaching: Social Constructivist Perspectives, (New

York: Peter Lang Publishers

Taylor, P C (2004) ‘Transformative Pedagogy for Intercultural

Research’, Culture Studies in Science Education, Kobe University, http://pctaylor.smec.curtin.edu.au/publications/Transformative%20Research.pdf

Twining, W (1967) ‘Pericles and the plumber: prolegomena

to a working theory for lawyer education’, Law Quarterly Review, 83,

396-426

Twining, W. (1973) Karl Llewellyn and the Realist Movement.

(London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

Walker, S A (2004) ‘Socratic Strategies and Devil’s Advocacy

in Synchronous CMC Debate’, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning,

20, 3, 172-82

Wenger, E. (1998) Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning

and Identity, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

West, C. (1989) The American Evasion of Philosophy: A

Genealogy of Pragmatism, (Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press

White, G E (1978) Patterns of American Legal Thought,

(New York: Lexis Law Publishing